That imperative sounds far easier than it actually is. The people who live in many of the neighborhoods served by this city’s historically African-American churches are no longer predominantly African-American. In fact, parts of Crenshaw and Compton now have large Hispanic majorities. The census tract that is home to Najuma Smith-Pollard’s St. James AME Church is 82 percent Latino.

“Immigration,” Chip Murray tells the 2010 PTM fellows at their graduation, “is the single biggest challenge our community has faced since the civil rights era. We are becoming a nation of nations.”

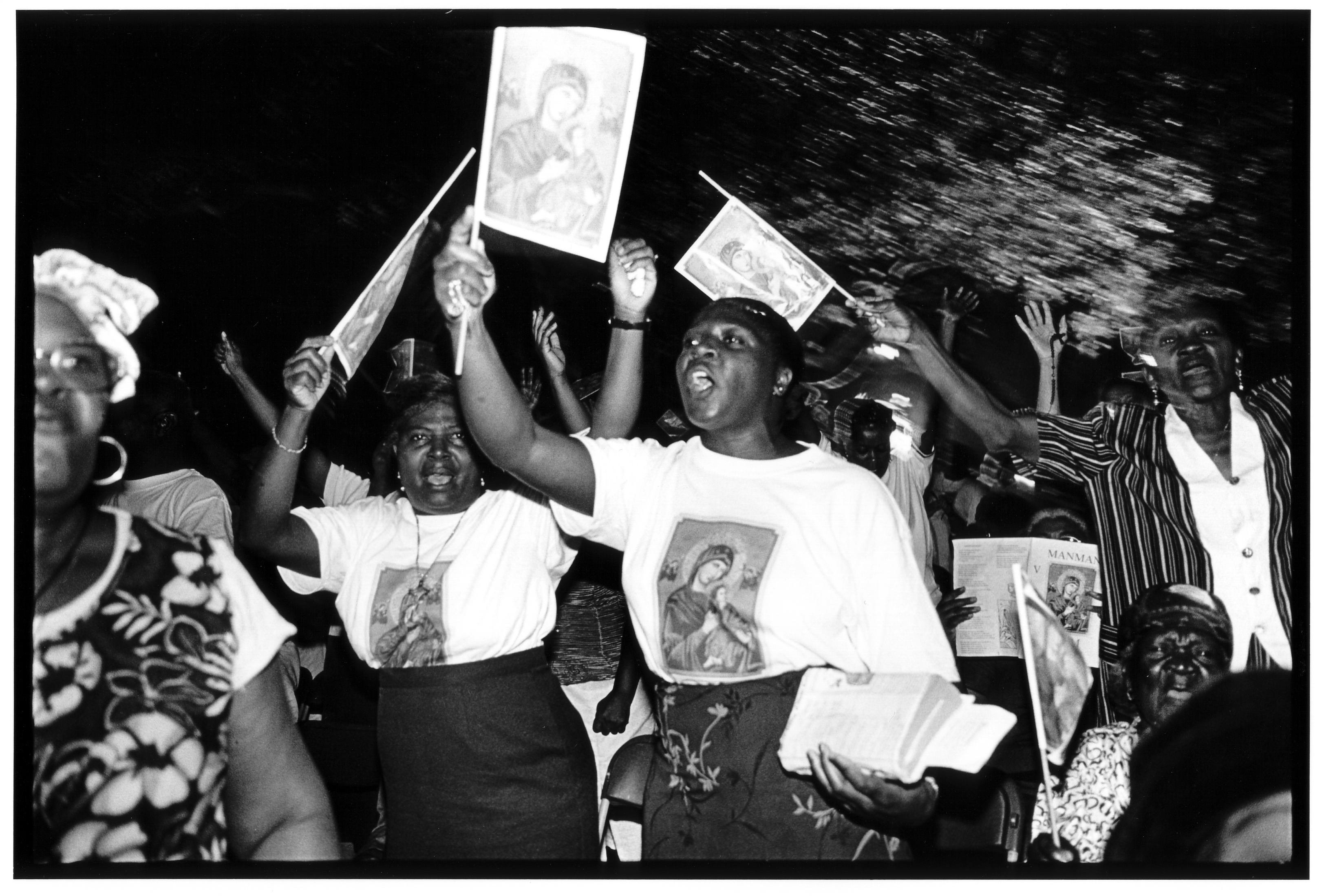

One response of black churches to the loss of demographic cohesion in their communities has been to turn inward—a reversal of a legacy of religiously-inflected civic engagement that is in some ways indistinguishable from the history of the 1960s.

A recent report from the Public Influences of African-American Churches Project (PIAAC) at Morehouse College determined that black churches emerged from the decade with considerable political momentum both from their successful public policy activism and from enhanced electoral opportunities achieved as a result of that activism.

“But while there is ample evidence that African Americans have built effectively upon that electoral momentum,” the report states, “there is very little evidence of large-scale public policy engagement by rank-and-file blacks over the last 40 years.”

The PIAAC research team reached a pair of conclusions: first, that the influence of black churches within their own communities has been impaired by a lack of infrastructure devoted to policy advocacy and civic interaction. And, second, that the best remedy for this situation is civic capacity-building among church leaders through intergenerational and inter-ethnic dialogue about churches and public life.

Providing a model for building that needed infrastructure and coaxing the black church’s latent capacity for civic engagement back to life were the primary goals of the PTM staff at the outset of the program. The purpose of Phase IV—encouraging the ongoing accumulation of social capital through an active alumni network—is to sustain that momentum into the future.

And, to accommodate new demographic realities, this process of activism and network-building must eventually extend past the comfort zones within which many black churches have traditionally operated. 1

“We have to follow the Lord’s example,” says Dr. Michelle Stewart-Thomas, a therapist and PTM instructor. “That means we have to be willing to do a new thing—even if that means stepping outside our established religious and cultural boundaries.”

In fact, a number of program participants are already beginning to adapt to this changing landscape. “I live in suburbia,” says John Wells, head pastor of Mountain View Community Church in Temecula and a 2008 PTM fellow. “So even though I’m an African American pastor and we’re predominantly African American, because we don’t have a quote-unquote ‘black’ community, our church isn’t race- or ethnicity-driven. It is more community-driven.”

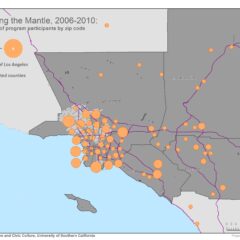

Wells’ identity as one component of a broader mosaic points toward the two most important elements of Phase IV of the PTM program: first, a network of 200 alumni in the Los Angeles area who will continue to serve as sources of knowledge for one another and, second, a culture of civic engagement that honors but also reaches beyond the particular concerns of African-Americans and the black church. In practical terms, this ongoing collaboration ensures that alumni will begin to reflexively look for ways to effect positive change in the increasingly diverse communities where they live and worship.

Moreover, like sturdy scaffolding that can be used to construct a variety of buildings, the essentials of the PTM program are designed to be useful not just in the black church but in any community where religious commitment entails a call to social engagement. In other words, the broad outlines of PTM’s curriculum can serve as a template for training programs in an array of faith-based organizations—from Latino advocacy groups to Muslim civic leadership initiatives.

“Every major faith tradition speaks to justice,” says Jared Rivera, former executive director of L.A. Voice PICO, part of a national organizing network that works with religious congregations to increase community activism and civic engagement. “What that means in modern-day America or a modern-day Los Angeles when you have to have decisions about how to create more affordable housing or how to improve schools—it’s very difficult to navigate. So what we try to do is try to translate those collective religious values into the creation of just public policy.”

Refining and then replicating the PTM formula will thus be the real measure of the program’s success. In other words, the leadership network should ideally grow beyond the boundaries of ethnically or denominationally distinct communities to serve as the matrix for broad-based movements for social change. The center of gravity for any given iteration of the program will vary—perhaps there will be a Muslim or Latino gray eminence like Chip Murray, or a supportive institutional home like Harvard Divinity School or USC—but the common result should be a diverse community of activists who can speak the same language.

“If the questions are asked by the leaders of our faith communities,” Murray says, “the solutions will ultimately present themselves in a way that includes all of us.”

That sentiment may sound naïve. But at a time when the constituencies served by many congregations are suffering and no othersource of succor is apparent, the leadership and advocacy of people of faith is not simply desirable. As Bob Herbert reminds us in “Too Long Ignored,” it’s essential.

Download a PDF of the report

Nick Street was a senior writer with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.