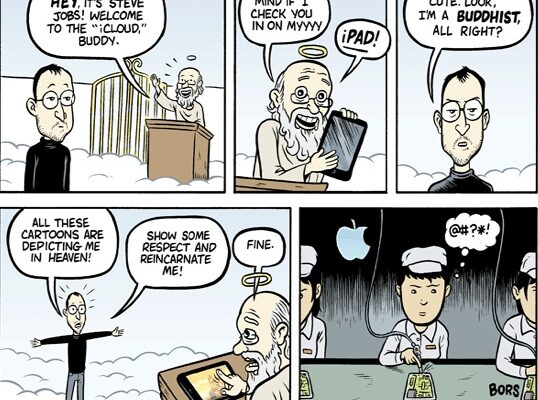

Cartoon by Matt Bors.

Last week I met Gary Wexler, who teaches in the communications management program at USC’s Annenberg School. The two of us were having lunch with my CRCC colleagues Richard Flory and Brie Loskota.

One the most intriguing topics that we covered was what Gary called “undulating space”—in essence, a more intentional and carefully tended version of our lively but deliberately casual lunchtime conversation at a bustling but comfortable restaurant. As Gary put it, the two main purposes of this space are to allow for the “synthesizing of disparates” and “turning complexity into simplicity.”

In other words, undulating space allows a new form of order to emerge from a period of contained chaos. We’d touched on a working definition of innovation! The propellers on all of our geek hats spun wildly.

But what does undulating space actually look like? How could we move from this abstract, cruising-altitude description of innovation to a working example on the ground?

Later that afternoon I stopped by Gary’s class on “Copywriting and Creativity.” Students in the class were a few chapters into Walter Isaacson’s recent biography of Steve Jobs. The day’s assignment: Break into groups of three or four and write the 10 most compelling ideas in the chapter on a big piece of butcher paper. These idea rosters were then taped to a wall, and a leader from each team talked for a couple of minutes about one idea that stood out from the rest.

I had fun playing around with the ideas along with the rest of the class, but two seemingly contradictory aspects of Jobs’ creative process really caught my attention. The first was his reverence for the romanticized outlawry of pirate culture during the European “Age of Discovery.” (Jobs is often quoted as saying, “It’s better to be a pirate than join the Navy.”)

A few minutes later, an intense but earnest young woman said that she was most impressed by the way Jobs configured workspace as a way of facilitating “his pursuit of perfection”—particularly the unadorned, all-white room away from Apple’s main campus that served as the creative crucible for Jobs and his inner circle of wizards, ubergeeks and brainiacs.

Fascinating! What does it mean to be a pirate in the white room?

For me, three disparate elements came together during and in the heady hours just after Wexler’s class:

- First and most obviously, the compelling metaphor for innovation that sprang from our classroom conversation about Steve Jobs (when I got back to work I began babbling about “pirates in the white room” to my colleagues).

- Up to now, our research team’s effort to distinguish innovation from, say, emulation has been a bit like Justice Stewart Potter’s remark about what constitutes pornography: We know it when we see it. The piratical metaphor from Wexler’s class suddenly gave me a way to talk about what’s happening among innovative groups in a much more focused and comparative way.

- Steve Jobs isn’t the only disruptive technologist to have a thing for pirates. The contemporary anarchist writer Hakim Bey begins his best-known essay—on what he calls the Temporary Autonomous Zone, or TAZ—with an appreciation for the very sort of pirate utopianism that inspired Jobs. And Bey’s writing on the TAZ was one of the key sources of inspiration for the Cacophony Society, which provided energy for the movement that would eventually evolve into Burning Man—a cultural touchstone for many spiritual-but-not-religious “nones.”

With all of this in mind, I realized that many of the “innovative”-tagged groups we’ve been studying might be described as exhibiting TAZ-like characteristics at some point in their recent history. This means that all of these spiritual innovators have, to greater or lesser extents, decoupled themselves from the authority structures of larger institutions and traditions, with the expressed intention of shaping new modes of practicing, ritualizing or organizing spirituality to meet the needs of particular communities.

And, either periodically or in an ongoing way, the key figures guiding each movement engage in a process of creative reimagining that allows for a varying degree of autonomy from the presuppositions that define their communities at any given moment.

In other words, they become pirates in the white room.

While some of these leaders might embrace this perspective on their work—the Rev. Dr. Neil Thomas of Founders MCC, for example, would likely take it as a compliment to be accused of multiple acts of flagrant spiritual piracy—others would almost certainly take offense. The leadership of a couple of genuinely novel yet nonetheless culturally conservative congregations would surely not welcome any association with the thought of someone as controversial as Hakim Bey.

That tension points to an important refinement in the application of the pirates-in-the-white room metaphor. For some innovative groups, the walls of the room form a tighter container, and the anarchic piratical energy is less intense. Holy Spirit Silver Lake regularly experiments with theology and liturgy, but the group’s commitment to its Episcopalian identity sets clear limits on how far members are willing to go with their experimentation.

On the other hand, the movements that have intrigued me most—and that have already begun to stand out as models of innovation for more traditional, less radically autonomous groups—are organized entirely around the deeply moral impulse to serve others. By pledging allegiance to no particular religious authority or identity, these movements are attracting participants from a stunning array of religious traditions, as well as from the rapidly growing ranks of the “nones.”

For these pirates, the walls of the white room are pushed back to encompass the whole world.

That expansive vision with compassion at its heart is, for me, an important marker of religious genius—William James’ term for the experience variously described as transcendence, oneness or the sublime. Now I’m on a quest to find spiritual pirates and the white rooms where they gather. Aaargh!

Nick Street was a senior writer with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.