This article was originally published on Tricycle with the support of CRCC’s global project on engaged spirituality.

Monastics in long brown robes entered the hall for formal lunch in order of seniority, the longest ordained members of the Plum Village tradition leading the way. Monks on one side of the room and nuns on the opposite, they sat down on purple mats and pillows and adjusted their robes like blankets over their crossed legs. Backs straight, hands in their laps, eyes cast down or closed, they waited as their brothers, sisters, and lay visitors—about 200 people in all—filled in the rows behind them.

One mat at the front of the room was left empty, covered in a simple brown quilt. An orchid with twenty delicate yellow flowers sat in front of it, along with a simple wood placard bearing the word Thay. Thay is Vietnamese for “teacher,” and the placard held the seat of the founder of the community, Thich Nhat Hanh. In January of 2020, when I visited Plum Village, Thich Nhat Hanh had already moved back to Vietnam to live out the last of his days at his home temple. He died in January 2022.

Thich Nhat Hanh wrote more than one hundred books, and his teachings on mindfulness, engaged Buddhism, and interbeing (his word for interconnectedness) have been influential within and beyond Buddhism. His legacy can also be seen in the formal lunch—monastic and lay students together seeking to embody what he taught.

Thich Nhat Hanh did not name a successor. If the Buddha is to be reborn in the 21st century, “he will manifest in the form of ‘A Beloved Community,’” he wrote, referencing Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision of a community committed to equality, justice, and nonviolent reconciliation.

Yet our attachments to our egos can impede harmony even among the most well-intentioned followers. From the Buddha’s death onward, power struggles and division have resulted in the development of various schools, often with differing ideas about the transmission of authority. Throughout history and into modern times, Buddhist sects—as well as those within Christianity, Islam, and other religions—have splintered following the passing of charismatic leaders.

Such leaders, the foundational sociological thinker Max Weber theorized, earn their authority based on their charisma or “divinely conferred” gifts. There is contention among scholars about how Weber’s theories apply to Eastern and nontheistic cultures, says Rhys Williams, a sociologist who studies religious organizations at Loyola University Chicago. Yet he adds, Thich Nhah Hanh undoubtedly held authority grounded in his unique qualities and abilities, to use a more secular definition of charisma.

Charisma allows leaders to push boundaries and bring social change, for better or worse, which also makes their deaths a particularly volatile time, Williams explains. In communities that survive the loss of a charismatic leader, Weber saw that authority tends to move to either the person who can claim the closest connection to the past leader or to the person who qualifies based on an agreed-upon set of rules, such as winning an election. In these ways, charisma becomes institutionalized, allowing it to last beyond the lifetime of a singular person.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s death offers an opportunity to see how the dynamics play out in one Buddhist community today. Since his stroke in 2014, his followers have tried to maintain the ineffable qualities that lent him his charismatic authority. For his monastic continuation in particular, doing so presents intertwined challenges: they must maintain a young tradition and stay true to his spirit by pushing at its bounds—all while no single person holds authority.

Establishing a Tradition

Fred Eppsteiner, founder and dharma teacher of the Florida Community of Mindfulness, met Thay in the 1970s. At that time, Eppsteiner said, “there was no Thich Nhat Hanh tradition, there was no Plum Village tradition. It was just him and just his freewheeling, creative way, his experimental way of responding to society, and the people who came to him for the great knowledge of Buddhist philosophy, psychology, and meditative practices that he offered for their benefit.”

Over time, his teachings, poetry, chants, and practices—such as formal lunches, walking meditation, and his Touching the Earth and Beginning Anew practices—have coalesced into a tradition. This tradition is rooted in Vietnamese monasticism as well as in the reform movement that sought to modernize Vietnamese Buddhism.

“Considering the amount of innovation that we associate with Thich Nhat Hanh, it’s important to note the amount of tradition that is also present,” says Jeff Wilson, a scholar of Buddhism in North America at the University of Waterloo, Ontario.

In the midst of the Vietnam War, Thich Nhat Hanh started the Order of Interbeing as part of his efforts to apply Buddhist thought to the modern world. When he ordained six social workers into the new order, he gave them fourteen precepts of Engaged Buddhism—now called “mindfulness trainings”—as spiritual tools to help them as they worked for peace and rebuilt bombed-out villages. These were a modern interpretation of the bodhisattva precepts.

They must maintain a young tradition and stay true to his spirit by pushing at its bounds—all while no single person holds authority.

In the early 1980s and by then exiled from Vietnam, he and Cao Ngoc Phuong, one of the six Order of Interbeing members, established Plum Village as a practice center in the south of France. Thich Nhat Hanh reopened the Order of Interbeing to followers from the Vietnamese diaspora as well as Western students. Then in 1988, Phuong—now Sister Chan Khong—and a few others became Thich Nhat Hanh’s first monastic students, vowing to live celibately and follow a modernized monastic code.

Eppsteiner, one of the first Americans to join the Order of Interbeing, describes those years as a period of increasing formalization, with the monastic body becoming the central organization. The Order of Interbeing’s charter emphasized the equality of laypeople and monastics, as well as a nondenominational approach to Buddhist teachings, Eppsteiner says. By becoming a formal tradition centered on monastics, he says, “the danger is that it will become what Thay rejected.”

Orlaith O’Sullivan, who has been a member of the Order of Interbeing since 2012, says that monastics and laypeople play complementary roles. She repeats an image from Sister Jina, one of Thay’s first European monastic disciples: Plum Village is the palm of a hand, and laypeople are the fingers that go out and work in the world.

As a volunteer, O’Sullivan has built practice communities in Ireland and coordinated the activities of the Wake Up Schools movement, an international network of classroom teachers practicing mindfulness. Practitioners may turn to monastics for answers due to the monastics’ deep commitment to the practice, she says, but “I think we all try to be a refuge for people.”

The monastics estimate that up to 200,000 people have committed to Plum Village’s Five Mindfulness Trainings for laypeople. Practitioners can deepen their practices with others through more than 1,000 local and online sanghas. To help laypeople get started, Plum Village offers a “sangha in the box” package with materials and guidance for facilitating a group, but there is little additional support or oversight.

“It’s a fine line between organizing and getting involved, and then staying away from becoming like a Vatican—centralized,” says Brother Chan Phap Dung, a senior dharma teacher.

Each region or country has its own organizations for the Order of Interbeing. Laypeople in these organizations put forth and mentor new applicants to the order and new lay dharma teachers, with monastics providing final approval to these applicants. There are more than 3,000 members of the Order of Interbeing around the world.

According to the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation’s 2022 annual report, 533 monastics live in eleven practice centers, situated in France, Germany, the United States, Australia, Thailand, and Hong Kong. Sister True Dedication sees Thich Nhat Hanh’s decision to ordain monastic students as forward-thinking. “There is something about the monastic commitment—about the monastic precepts and the way that the body, held by the monastic code of conduct, can hold the dharma, hold the practices, find the future and carry it forward,” she says.

The Monastic Continuation

Tall, thin, and with a wide grin, Sister True Dedication had blonde hair before it was shaved off on her ordination day in 2008.

Thich Nhat Hanh was not serving as abbot when she left her life in Britain to join Plum Village in France, but as teacher he largely set the agenda. For instance, True Dedication remembers how he declared the monastery vegan, seemingly overnight, shortly after she became a nun. Her diet at the time consisted largely of yogurt and cheese, she says with a laugh.

Then in his 80s, Thich Nhat Hanh was busy establishing new initiatives: the Wake Up movement for young adults, Wake Up Schools for teachers, Institutes for Applied Buddhism in Germany and Hong Kong, a monastery in Thailand, and an online sangha.

As a young nun, True Dedication was an eager volunteer. Formerly a journalist with the BBC, she became Plum Village’s communications liaison, working on everything from websites and press releases to books. She worked closely with Thich Nhat Hanh and Sister Chan Khong on efforts related to climate change, human rights, and other social issues.

Working at a computer, however, was not what True Dedication expected of monastic life, and Thich Nhat Hanh was demanding. She once tried to refuse her teacher’s request for assistance, saying she was working in the garden instead.

“Working in the vegetable garden, helping Thay, it’s all the same,” she recalls him responding. “I think Thay was saying, ‘You need to dare to find peace in the action.’”

Religious organizations need considerable resources—both financial and human, says scholar Jeff Wilson, and monastics serve as a spiritual workforce. Traditionally in Buddhism, the lay community has supported the monastic community financially in exchange for karmic merit. At Plum Village, the conviction that they are working to improve the world helps motivate monastics to work for no personal financial gain. It also motivates laypeople to support them. As such, Wilson calls Plum Village “an exemplar of a post-merit model.”

Buoyed by their closeness to Thich Nhat Hanh, book sales, and dana given for retreats, the monastic body has been sustained by this model since Thich Nhat Hanh’s stroke.

Now a dharma teacher, True Dedication sees her role as supporting younger monastics as they learn both the organizational and spiritual lessons of their work. “The sangha career becomes our career,” she says.

No-self Leadership

Whenever Thich Nhat Hanh gave a retreat or spoke in prominent places, he always traveled with an entourage of brown-robed monastics. It was an intentional effort to deflect attention from his singularity, according to Brother Phap Dung, who joined the monastic order in 1998.

Nonetheless, “our teacher provided the leadership,” he reflects. “We’re under his aura.”

His singular role became an issue in 2009 when Thich Nhat Hanh developed pneumonia on his US tour. While he recovered at Massachusetts General Hospital, a thousand people gathered in Estes Park, Colorado, for a retreat aptly themed “One Buddha is not enough.” A book by the same name captured dharma talks and reflections from the weekend.

Participants shared how, as they overcame their disappointment, they began to see their teacher first in the monastics, then in each other, and finally in themselves. “Here was interbeing, right before our eyes. Thay and the Sangha were one and the same. We and the Sangha were one and the same. Here was Thay, present with each of us, in each of us,” wrote Soren Kisiel, who joined the Order of Interbeing on the retreat.

The idea of no-self theoretically would prevent Buddhist groups from becoming cults of personality, Wilson says, “and yet the history of Buddhism is full of this.” What is unique about Plum Village, Wilson adds, is that it came to a horizontal power structure without struggling through a major scandal, as has been the case with a number of Buddhist groups.

Monastics provide a “check and balance” on each other, Brother Phap Dung says. Practices such as rotating mentors, reciting the precepts every two weeks, living in close quarters, and providing each other with feedback allow the “sangha eye” to see issues before they grow and make decisions together.

“We are now in the process where we’re encouraged not to say, ‘Thay would do it like this’ or ‘Thay would say that,’” Phap Dung says. “Our teacher had an opinion, but now we need to deal with each other.”

Nonetheless, Thich Nhat Hanh’s presence was palpable on the retreat I attended months before the pandemic. Many retreatants came because they had read one of his books. Participants gathered around a screen in the Dharma Hall to watch one of his talks given years earlier. At the end of walking meditation one day, the group came to a tree shading a statue of the Buddha. After a monk shared that Thay had planted the tree, retreatants reverentially approached to touch it.

In dharma talks, monastics repeat imagery that Thich Nhat Hanh once used to explain profound concepts. Just as he did, they will hold up a piece of paper to illustrate “dependent arising”— like the two sides of a paper, left and right, joy and suffering cannot exist without each other. Even their script on a whiteboard resembles their teacher’s.

“Thay and the Sangha were one and the same. We and the Sangha were one and the same. Here was Thay, present with each of us, in each of us.”

In order to continue its influence, Wilson says, Plum Village “will need to produce communicators of a similar level from within who also pique people’s particular interest—without, however, developing too much of an ego complex.”

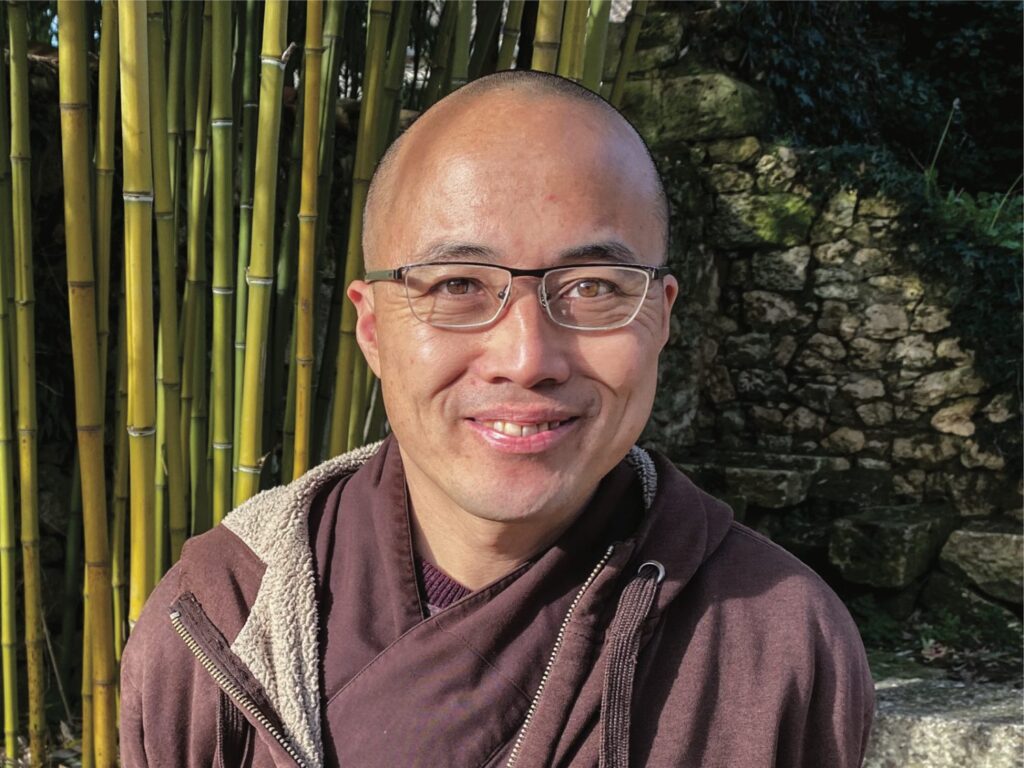

Younger monastics told me Phap Dung was a Zen master. Retreatants seek him out for private consultations and hang on to his every word—though not as they might have Thay’s poetic language. There is a lightness and informality in Phap Dung’s speech, peppered with laughter.

He and his family escaped Vietnam, and he spent his formative years in Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley. He reveals the anger he felt toward his father as a young person and his grief at his passing. A week after Thich Nhat Hanh’s death, he let tears flow during a talk watched by tens of thousands on YouTube.

It’s not just him, Brother Phap Dung says. People look to all the elder dharma teachers for guidance now. “For me there is less pressure to be like Thay or to fill in something which is not fillable. You just do whatever matches your capacity and your interests as you grow,” he says.

A Process for Change

At a question-and-answer session during an online retreat in 2021, a lay practitioner pressed the monastics about the place for nonbinary individuals in a very gendered monastic tradition. Brother Phap Dung responded that Buddhism has continually adapted to new contexts throughout its history. Plum Village’s center in California, for example, once experimented with bending the lines of cushions that typically separate women and men during formal lunch into an arc, recognizing the spectrum of gender identities.

While monasteries in other cultures would not have taken such an action, Phap Dung acknowledged, the monastics are increasingly aware that the tradition itself can be a source of suffering. The mindfulness training on “True Love,” for instance, once said relationships should be recognized by family, which is impossible for those whose families have rejected them due to their sexuality.

A few months after Thich Nhat Hanh’s death, Plum Village announced that it had revised the training. “I resolve to find spiritual support for the integrity of my relationship from family members, friends, and sangha with whom there is support and trust,” the new text reads. It also now includes a line about not discriminating “against any form of gender identity or sexual orientation.”

Thich Nhat Hanh tasked his monastics with keeping the tradition adaptable, which means revising anything from mindfulness trainings to rituals. To enable the community to do so, Thich Nhat Hanh taught the monastics how to make decisions on their own, Phap Dung explains.

The process of consensus that he taught builds upon Plum Village practices of deep listening and nonattachment of view, as well as precedent in Buddhist history and scripture, which reference majority voting within monastic communities. The ultimate decision-making body is the council of fully ordained monks and nuns.

When a proposal is made to this council, those who agree are asked to remain silent, while others have an opportunity to voice their dissent. The proposal is accepted when all remain silent.

The process, Phap Dung explains, is “an opportunity to practice, to watch your mind. You should have an opinion, you should be able to express it, but you should also be ready to let it go and be affected by others.”

When the idea to revise the mindfulness trainings was raised in the midst of the pandemic, Phap Dung facilitated an asynchronous consensus-building process among the international dharma teachers’ council. “There was an exchange of over one hundred emails back and forth,” he says, smiling.

Watching ideas grow via the email thread while others withered was fun—“like watching something organic,” Phap Dung says. As the edits coalesced, he set a date by which any additional changes could be suggested. Acceptance was determined by the email thread going silent.

Thich Nhat Hanh had revised the mindfulness trainings twenty years ago in consultation with a small inner circle of students. One of his revisions at that time was to add “not contributing to global warming” (now “climate change”) to the practices. The change would influence later actions, such as the practice centers going vegan and monastics supporting the international climate accords.

Likewise, some of the retreat centers have already made changes to help LGBTQ+ practitioners feel more welcome. For instance, some centers have created all-gender bathrooms and “rainbow” camping sections for those who don’t feel comfortable—or welcome—staying with either the monks or nuns.

Plum Village, however, is not the most progressive Buddhist community on identity issues. “We’re still a very binary culture in the monastery,” Phap Dung says. For now, it is up to practitioners to find their place within that culture.

“We have to be skillful to know how to organically evolve together,” Phap Dung says, adding that consensus is not about achieving agreement but rather about staying committed to the practice and community as it develops. “This is a big step for us, because we now have a process for change,” he says. “This is the first time we’ve done something on this scale without our teacher.”

Planting the Future

Before Thich Nhat Hanh’s funeral and cremation, monastics gathered to hear tributes to their teacher in the narrow hall in Tu Hieu Temple in Vietnam. Thich Nhat Hanh’s body lay in a casket behind an altar. His empty mat, with flowers and tea set before it, formed part of an inner circle around which the rest of the mats were shaped.

As part of the ceremony, a monastic read a letter edited from Thich Nhat Hanh’s previous writings for this occasion. Monastics and lay practitioners form a “complete multifold sangha,” it read, using an inclusive term for the fourfold sangha, which refers specifically to male and female monastics and laypeople. The word choice perhaps foretold the revisions to the mindfulness trainings. “The monastic sangha and the lay sangha rely on one another, support one another, practicing to transform and serve all living beings,” the letter read, calling upon practitioners to take refuge in the sangha.

Serving as Thich Nhat Hanh’s continuation requires preserving his memory, his teaching, and his beloved community. It also means pushing the bounds of his tradition.

According to Max Weber, religious groups inevitably go through a process of “routinization” following the death of a charismatic leader. Sociologist Rhys Williams notes that it’s difficult to find an example of a religious organization that does not follow this path. In Weber’s model, Williams explains, authority “becomes stable, repeating, established—institutionalized either in traditional or legal processes—until a charismatic challenge rises again.”

Everything is impermanent, the monastics say, but they are also confident as they approach the future without their teacher. During the period of transition between Thich Nhat Hanh’s stroke and his death, the retreats continued to attract thousands of participants annually. Just days after his death, seven people joined the monastic communities in France and the US, vowing to transform their suffering and bring happiness to all beings.

Plum Village is like a forest—a refuge and place of refreshment for all those who come to it, Sister True Dedication says. Thay was a huge tree in that forest, she continues. Though his tree has fallen, it continues to nourish the soil so that new trees may grow.

“Thay has left us all his teachings, all his research, all his guidance, all his ideas for how we should organize and make decisions, and also all of his dreams for the work that he wanted us to do in the wild,” she says. “It’s very rich earth.”

Click here to read the full article on Tricycle

Megan Sweas is the editor and director of communications with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.