Nobody ever said religious innovation was easy—either as an undertaking in the context of a religious community or as the subject of a scholarly investigation.

For one thing, creative and innovative activity within a religious group is not always self-evident. And members of a community that is intentionally developing new ways of doing old things can disagree about what counts as innovation and what options are out of bounds. In fact, many of the people we’ve talked to as part of our Religious Competition and Creative Innovation project are hesitant to call what they are doing “innovative” since that implies that they and other members of their community are actively working toward some sort of foundational religious change. On the other hand, some true innovators are defending their innovative programs and ideas against traditionalists in their own ranks.

One pastor said that he was “surprised” that we would consider his church “innovative and creative” since it had recently undergone what he called a “fundamentalist uprising” that felt like a “long season of ‘Survivor’.”

Yet religious change is inevitable, even within groups that claim they “never change,” which would mean (in their view) forsaking historic traditions that are inseparable from their identity.

What drives innovation and change within and between religious groups? To date, we’ve visited and interviewed leaders and members from more than 30 congregations in Southern California that, from our perspective, are pursuing their religious and spiritual goals in innovative and creative ways. It wasn’t until this past weekend, however, that I started thinking about forces that actively work to inhibit innovation, creativity and change.

Brian Houston, the senior pastor of Hillsong Church, which has a new church plant in downtown L.A., was reported to have said that his church was “having an ongoing conversation” about same-sex marriage. Hillsong, which has 30,000 members worldwide, produces music that is played in churches around the globe—making Houston, and Hillsong, an important voice in the evangelical and Pentecostal worlds.

But in those worlds, at least until the recent past, a recognized leader who doesn’t unquestionably oppose any acceptance of LGBT equality will inevitably receive denunciations from almost every quarter. This is nothing new, as evangelicals (and their early 20th century progenitors, the fundamentalists) have long patrolled the boundaries of their movement to ward off wayward beliefs, practices and behaviors. Moreover, they have frequently mobilized to punish any organization that choses to blur these boundaries.

This is why Andrew Walker, director of policy studies for the Southern Baptist-sponsored Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, excoriated Houston and condemned Hillsong as “a church in retreat.” The day after Walker’s screed appeared, Houston published a response and clarification on the Hillsong website, stating that Hillsong’s “biblical” position on gay marriage was unchanged.

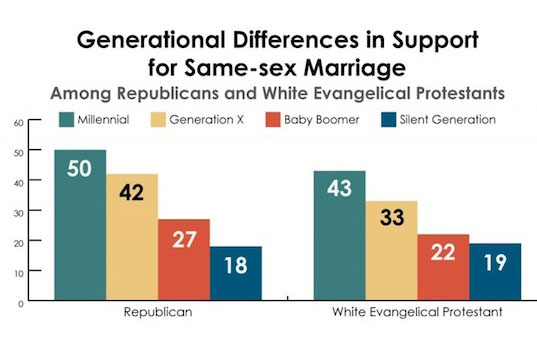

Still, all of this is unfolding in the context of greater acceptance of LGBT individuals in general, and in particular within evangelicalism, suggesting that evangelicals are no longer speaking with one voice on LGBT issues (including gay marriage). Surveys show that support for same-sex marriage remains a minority position within evangelicalism, even among younger evangelicals. Yet there are increasing numbers of evangelicals who are publicly acknowledging both their gay or lesbian sexual orientation and their commitment to remain “evangelical.”

Walker argued that evangelicalism can’t change and still be evangelical, and that evangelical theology can’t accommodate gay marriage and the acceptance of LGBT identities and relationships. But since there is no “Pope of evangelicalism,” you can’t get kicked out of the movement (regardless of the many public proclamations about what constitutes an “evangelical” in good standing), so it remains to be seen how this issue will ultimately play out.

Which leads to the question: How do religious groups manage the change that they will inevitably experience? Over its long history evangelicalism has changed: Evangelicals were at the forefront of the anti-slavery movement in the 19th century, became defenders of racial segregation in the mid 20th century and are now (at least in some quarters) re-emphasizing a socially engaged spirituality—something that, in 1947, noted evangelical theologian Carl F.H. Henry decried as having been lost by evangelicals.

Will the scope of the ongoing process of change eventually expand to include the recognition and acceptance of LGBT individuals (and their relationships) within evangelical institutions? Can the boundaries of “acceptable” beliefs and behaviors continue to be as effectively policed as they have been in the past, given the multiple and often competing forms of authority that we all encounter? And what kinds of change can evangelicalism, or any religious movement, undertake and still maintain its “authentic” religious identity?

Innovation has become a cultural buzzword—almost to the point of losing its original meaning (think of the fate of the word “awesome,” for example). Still, there are plenty of religious groups that are innovating. And the fact that it is often painful and frequently messy makes religious innovation all the more worthy of study.

Chart and survey data from the Public Religion Research Institute.

Richard Flory is the executive director of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.