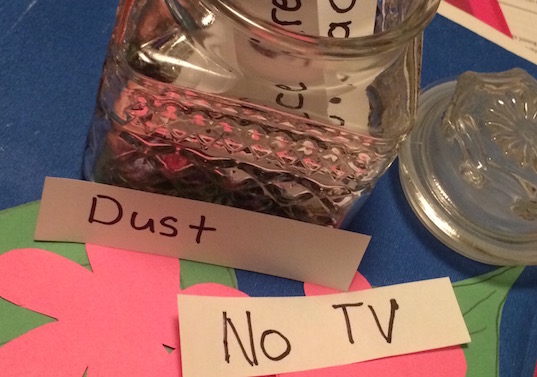

I must admit that the first mention of Lent brings back haunting memories. In our house, each day we randomly picked something to give up from a jar of little paper slips of horror. Each day we prayed that we would not miss a favorite TV program in a world yet to include DVRs or even VCRs. Successfully completing—or “surviving”—the day was rewarded with a construction paper cutout of a leaf or flower that we tacked on a felt board. By Easter the board had transformed from bleak winter to bright and cheery springtime. With modern times came online resources such as a printable Lent calendarto track the days leading to Easter.

Out of respect for the Catholics and other Christians who faithfully observe Lent, it is important to acknowledge the sacrifice, service and prayers that characterize their experience of the 40 days before Easter. Lent is meant to be a period of reflection, self-restraint, almsgiving and humbly appreciating the sacrifice of Jesus during the days leading to the crucifixion and Easter resurrection. Pope Francis characterizes Lent as a time of renewal and grace.

Some Catholic adults may appreciate the intention of Lent, yet may not observe it with complete reverence and self-restraint. As one of these Catholic-lite adults, my memories of Lent are associated with parental-driven, forced sacrifices of TV privileges, missed dessert, extra household chores and other child-centered “punishments.” Lent appeared to be a time when Catholic-schooled parents pass down their own even more regulated experiences of fasting and loss of favorite childhood vices.

By describing my childhood experience of Lent, I don’t mean to expose the perceived petty burdens of some middle-class children. Instead, I hope to illustrate that the solemnity of Lent for Catholic youth may be constrained by the cognitive development level of the average child. Many children are unable to associate “giving up” candy with the adult concept of building the restraint necessary to reject evil and the temptations of sin. This childhood understanding of Lent also can affect our adult response to the season.

It is no wonder that by adolescence many of us who were finally allowed to choose our own sacrifices were less than compliant with the intentions of the church to teach sacrifice, self-restraint and charity. Rather, Lent became a time to test limits and trivialize a sacred tenet of our religion.

We would give up foods we didn’t like, skip social events we didn’t care to attend or “help” with chores that didn’t need to be done (such as proposing to cut the grass every weekend when the yard was covered in two feet of snow). For me, an avid cookies-and-cream enthusiast, the loss of mint ice cream sounded legitimate yet was painless.

A friend admitted recently that every year she attempted to “give up” her little brother. Despite her mother’s annual unequivocal rejection of her offer to be deprived of a family member, she fondly recalls the bonding experience with her sisters as they joined forces in the attempt. The spiritual intent of Lent remained elusive to many of us throughout our formative years.

Today as an adult employed in a school of social work, I still struggle to find the connection between my temporary “loss” of white chocolate and Holy Week rituals such as the Passion of the Cross. My loss has no obvious gain for my community or my church.

Rather, my actions call to mind the current trend for some non-practicing Catholic Millennials to engage in self-improvement-driven Lenten rituals. Their behavioral change goals associated with Lent could be interpreted as more akin to the concept of New Year’s resolutions. Perhaps guilt related to years of superficial Lenten practices motivates some of us to renew efforts to better ourselves, at least for a month or so. Benefits for others continue to be missing.

When I was frantically searching for something acceptable yet not overly punitive to give up this year, a colleague mentioned that Catholics are being encouraged to commit acts of kindness this year rather than give up something. My initial reaction was regret that my aspirational plan to “give up” certain coworkers would not come to fruition. My next reaction was to seek evidence that the Lenten season could be reconceptualized as other-centric.

In the “Message of His Holiness Pope Francis for Lent 2015,” Pope Francis outlined a Lenten season filled with efforts to end indifference to the struggles of our neighbors, communities and world. These efforts include praying together to combat feeling powerless to make a difference, engaging in charitable acts toward others and recognizing our interdependence with others in facing and overcoming life’s challenges. At no point did the Pope emphasize the betterment of the lives of others through acts of self-restraint or self-centered resolutions.

In 2015, Lent coincides National Social Work Month. There is a remarkable overlap in messages between the Pope’s letter and this year’s theme, which calls for ongoing efforts to build, support and empower individuals who are most vulnerable and in need. According to the National Association of Social Work, “Positive social change is never complete. It’s a work in progress.” This dictum offers a secular perspective, yet underscores that it is not too late to shift from a sacrificial to a servitude approach to Lent. Irrespective of past Lenten transgressions in “giving-up,” meaningful observation of Lent through “giving-back” is within reach.

Getting Lent “right” is definitely a work in progress for some of us. But the overriding Lenten message of nurturing a merciful heart and offering love to others in need resonates deeply in a way that skipping dessert never will.

Photo courtesy of Stan Yamada

Ann Marie Yamada is a guest contributor with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.