Last week I took a walk on the gentrifying edge of Los Feliz with the pastor of a local church that mainly ministers to the down-and-out. We talked about the urban landscape around us as we passed through city blocks in the midst of a transition–new people are moving in, others are moving out.

We stopped in front of a busy restaurant and watched well-dressed, well-heeled people enjoying lunch on an outdoor patio. Such a scene is hardly unusual in Los Angeles, but it was new for this neighborhood. The upscale eatery served as a timely example of the change the pastor was explaining to me. Ten years ago, “people were scared to come here,” he said. “Now on Sunday mornings they line up all the way down the block waiting in line for brunch.”

There was no sarcasm or animosity in his voice, but the stylish restaurant–offering “organic, local and small-farm produce” and boasting over 1,000 reviews on Yelp– served as visible proof of an evolution in the neighborhood that the pastor could feel almost day-by-day. As we stepped away from the restaurant he asked a question that will be important to our research for the Religious Competition and Creative Innovation (RCCI) project: “I wonder if our congregation will gentrify too?”

Los Feliz and adjacent Silver Lake combine to form one of the “coolest” areas in Los Angeles, which puts this pair of neighborhoods high in the running for some of the coolest places on earth. How do you measure cool? In 2012, Forbes Magazine analyzed neighborhood data such as walkability scores, the prevalence of coffee shops, the percentage of residents who work in artistic occupations and access to food trucks. Based on the results of their number crunching they named Silver Lake as the “Best Hipster Neighborhood” in the United States.

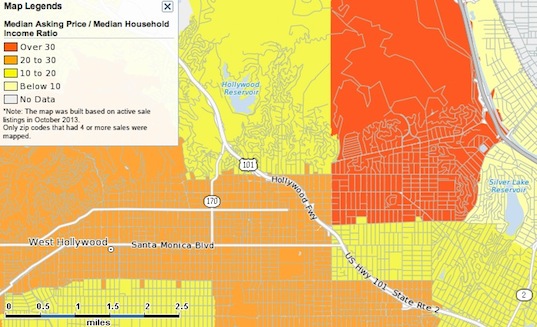

The writers at Forbes are not the only ones measuring cool. The Los Angeles County real estate website PropertyShark.com used a different data set to crown Los Feliz as L.A.’s “Most Rapidly-Gentrifying Neighborhood.” The researchers compiled neighborhood-specific data and created a ratio by comparing median home prices to household income as an indicator of gentrification. As the map above shows, Los Feliz–situated between the Hollywood and Silver Lake reservoirs–is literally red-hot.

Whether it is called urban renewal or gentrification, the process is not unique to Los Angeles. All across American cities, artists, recent college grads, yuppies and empty-nesters–largely but not exclusively white–are moving into strategically situated urban neighborhoods. In these urban spaces, locally sourced restaurants and Third Wave coffee shops inevitably begin to replace less glamorous establishments. Meanwhile, housing renovations and rising rents spur the departure of the previous residents, who are usually non-white and often immigrants. The specifics change from city to city, but the broader pattern has become predictable. What is less predictable is what happens to the religious groups located in these transforming neighborhoods.

Centro Cristiano Pentecostal is only a few blocks from vintage clothing stores and bars offering “hand-crafted” cocktails on Vermont Avenue in the heart of Los Feliz. But the Spanish-speaking church, where women wear calf-length dresses and the men tuck in their shirts, is still thriving even though the neighborhood looks a lot different now than it did in 1995, when the congregation bought the building. The three weekend services followed by potluck meals served in the parking lot draw over 400 worshippers. Combined with a Thursday youth service and two mid-week prayer services, this means that Centro Cristiano Pentecostal is a place of constant activity. Fewer members walk or take the bus to church than in the past, and many drive an hour each way to participate. But despite increasing commute times and the transformation of the neighborhood, the church shows no signs of slowing down and has no plans to relocate.

One of the questions we are pursuing in the RCCI project mirrors the question asked by the Los Feliz pastor last week when we stood in front of the restaurant: Do congregations gentrify? The pastor didn’t pose his question rhetorically, and we are taking that line of inquiry seriously as we conduct the fieldwork for this project.

Specifically, we’re not assuming that religious groups will follow the same gentrification patterns as the neighborhoods where they are located. Like Centro Cristiano Pentecostal, many congregations own their buildings and are therefore not impacted by rising rents or property taxes in the same way as other local residents. Members have emotional and historical attachments to their churches, which may keep these institutions alive even as restaurants around them update their menus, owners of residential buildings convert apartments into lofts and former corner stores become yoga studios.

On the other hand, longer commute times may decrease members’ ability to participate in church activities with the frequency they once did. That means that, over time, churches closer to home may become increasingly attractive to working families navigating very busy weeks.

Can an iceberg lettuce congregation survive in an arugula neighborhood? Issues of race, class, immigration, social change and, of course, religion converge in that question, so we’ll be gathering and crunching our own data to try to answer it.

Andrew Johnson is a contributing fellow with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.