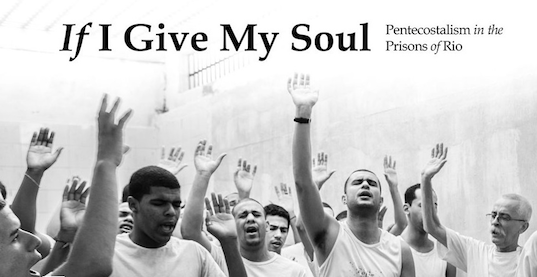

The familiar sounds of a Brazilian Pentecostal worship service flew from the open sanctuary doors of a church in Rio de Janeiro. The rattle of tambourines and shouts of “Gloria a Deus!” accompanied the dozens of voices belting out a well-known praise song. In many ways this church was similar to the thousands of other Pentecostal churches in Rio. The congregation consisted largely of people from the city’s poor and marginalized neighborhoods, and church leaders were appointed from within the congregation. Still, outsiders chided the church for being too legalistic. The pastor expected members to adhere strictly to the church’s lifestyle guidelines and faithfully attend the five weekly services and small prayer group meetings, as well as the community fasting campaigns. Though the congregation was certainly poor, they used the money they collected in the offering plate to purchase instruments for the worship team, a lacquered wooden pulpit, a functioning audio-system—even delicate lace doilies to cover the silver communion trays. But not everything about this church was typical. For one thing, it was located inside of one of Rio’s largest penitentiaries, and all of its members were currently incarcerated.

The prisons and jails of Rio de Janeiro are unexpected sites of religious innovation. Autonomous, inmate-led prison churches operate inside of every penal facility in Rio, and these prison churches use an organizational model that resembles the Pentecostal churches outside of prison. But, obviously, they operate in a very different environment. While they look to other Pentecostal churches for organizational templates, they have also taken cues from a different group: the prison gangs.

The first Pentecostal prison groups in Rio de Janeiro called themselves the Comando de Cristo (Christ’s Command), a name that was directly inspired by the most powerful gang in the city’s prisons, the Comando Vermelho (Red Command). These inmate sects evolved into prison churches and, again following the example of prison gangs, started to claim parts of the prison as their own. Church members began living together in what became known as the celas dos crentes (Believer’s Cells). Gang leaders now grant these churches autonomy, allowing prisoners to abandon their gang affiliation and move to the celas dos crentes as long as their conversion and subsequent practice are deemed genuine. The prison churches have considerably fewer members than the gangs, represent about ten percent of the inmate population—and never directly challenge the gang’s authority.

One of the reasons that Pentecostalism has been so successful on the marginalized edges of Latin American cities like Rio de Janeiro is because of its ability to promote indigenous leaders and incorporate organizational innovation that allows the churches to adapt to their social surroundings. Accordingly, the prison churches elect pastors, elders, secretaries and worship leaders from the prison population. Cristiano Silva, an elder in the Heroes for Christ Prison Church located in one of the Rio’s jails, said, “The church is ours. It belongs to those of us on the inside. Some churches from the outside come to visit, but there isn’t formal sponsorship, like becoming a legal entity…No, it’s a community church.”

His fellow Pentecostal inmates elected Cristiano into his position. If he is released or transferred from the jail, the assistant elder will take his place, and the remaining inmates will hold a vote to decide who will become the next assistant elder. This democratic promotion system ensures that the Heroes for Christ Prison Church will continue despite an inherently transient population.

Rio de Janeiro’s prison churches are not officially sponsored by any denomination or outside prison ministry. As a result the church’s theology, rituals, music and leadership structure are shaped by prison culture—an example of how innovative congregations, Pentecostal and otherwise, are able to succeed in challenging social contexts.

Preview “If I Give My Soul,” a film about Andrew Johnson’s research:

Andrew Johnson is a contributing fellow with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.