This radio documentary was produced by KALW’s The Spiritual Edge, with the support of CRCC’s global project on engaged spirituality.

To hear this and other profiles, subscribe to The Spiritual Edge podcast in your favorite podcasting app, including Apple podcasts, Spotify or Google Podcasts. Find out more on The Spiritual Edge website.

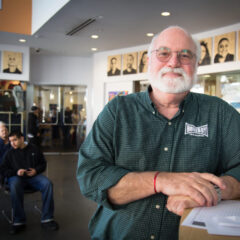

Father Ismael Moreno Coto – the Jesuit priest everyone calls Padre Melo – is a spiritual leader, the director of a radio station and one of the most respected political analysts in Central America.

In his native Honduras, he routinely speaks out against widespread human rights violations, fraudulent elections and government corruption. All these factors, and the resulting violence, poverty and inequality, have propelled streams of migrants out of the country. Padre Melo risks his safety to remain and support popular opposition movements.

Veteran journalist Maria Martin, based in neighboring Guatemala, visited Padre Melo during a typically busy week for him. Upon her arrival in San Pedro Sula, an area with a dangerous reputation in a country with a high homicide rate, Melo surprised her by picking her up at the terminal.

He doesn’t travel with bodyguards, and people recognize the 10-year-old truck he drives. On the drive from the airport, it didn’t take long for Melo to start talking politics. He drew parallels between the Honduran government – with its reliance on drug money and theft from the social security fund – and the United States government, run by a businessman.

Politics has been kidnapped in both countries, Melo says, no longer connected with ethics, but with personal profit. Around the world, he adds, democracy has become distorted and is in crisis. In his home town of El Progreso, about 150 miles from the nation’s capital, Tegucigalpa, he and his colleagues run an independent radio station that offers an open forum for commentary about the government that most Honduran media outlets wouldn’t dare broadcast.

That station, Radio Progreso, also includes some Catholic programs. It’s an outgrowth of the liberation theology movements that swept Latin America starting in the 1960s, when many clergy and lay people turned their focus on the needs of the poor. Radio became a form of educational outreach and an organizing tool.

“Radio Progreso,” Melo says, “is an offering for all the society, be they Catholic, evangelical, political, or atheists. It’s open programming, with a preference for the poorest.” In

the second-poorest nation in Central America, where more than half the population lives on less than five dollars a day, this priest identifies with those at the bottom of society.

He was the youngest child of a large family of agricultural workers. “My father cultivated land to grow corn and beans. My mother baked bread to sell in the banana plantations,” he said. “With what they made, they’d feed and clothe us.”

In their hometown, Melo’s older sister Ruth says of the rotund 61 year old, “he’s not only a priest for us. He’s also our little brother. We spoil him, he spoils us.”

Their father, she continues, was “a committed man, dedicated to the cause of justice for campesinos.” Her younger brother inherited that same passion, she says, even as he felt from early childhood that God had chosen him for a vocation.

As Melo studied for the priesthood, he connected with a Jesuit named Guadalupe Carney, whom he admired for his revolutionary ideals.

“I remember he told me, ‘So you’ve decided to become a Jesuit priest,” Melo said. ‘’Well then, he told me, remember that you are the son of a field-hand. So don’t you go and be a priest just for the rich. Remember you have to defend the poor campesinos. That’s always stayed with me.”

That defense includes writing scholarly articles, keeping up with political developments and showing up at demonstrations. Radio Progreso opened phone lines to callers commenting on how the brother of Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernandez was in a New York courtroom on trial for drug trafficking. Padre Melo also has attended demonstrations with opponents to the president calling for his resignation.

“The only thing they ask of me is to be present,” Melo said. “When I’m not there, sometimes, they feel vulnerable, but when I’m there, not saying anything, they seem to get some strength from my presence.”

After this demonstration against the president, the priest learns that police roughed up some of the protesters, and that an unknown assailant has attacked a Radio Progreso reporter in the nation’s capital, Tegucigalpa. He’s also the frequent target of attacks on social media.

Still, Padre Melo approaches people as a good friend who doesn’t take himself too seriously and who loves a good joke. Wherever he travels throughout Honduras, everyone seems to know this portly, balding priest.

A full auditorium at a university four hours’ drive from El Progreso turned out to hear him lecture against what he called “a policy of state terrorism which seeks to provoke fear among people in general in order to prevent any kind of opposition movement or social protest that might have impact on the policies of the extreme right.”

Becki Moreno, a human rights attorney married to Melo’s nephew, says the priest never seems to rest. His greatest contributions to his country, she suggests, may be his ability to mentor and inspire.

“He helps people by helping them to think, to analyze,” she says, “so that we can come out of that ignorance in which we’re submerged by some authorities in our country.”

This despite the authorities’ effort to shut down Radio Progreso. One of its commentators, Elvis Hernandez, recalled how in June 2009, a busload of military operatives arrived at the station, barged into the control booth and said, “We have orders to close this piece of shit.”

A day later, he added, the staff decided to resume programming, even as the threats continued.

The station staff faces constant reminders of the risks. On its walls hang photos and paintings of environmental and indigenous rights activist Berta Caceres, a good friend of Padre Melo’s. Attackers murdered her in March 2016. The Honduran government conducted an investigation, and three years after the fact convicted seven men in connection with her death. Caceres’ family and supporters – including Padre Melo – maintain that the masterminds behind her killing have not faced justice.

“We were very close friends,” Melo said. “I didn’t believe they would actually kill her.”

When he got word of Caceres’ death, he recalled, he had to deliver the news on the air.

“That our friend and compañera Berta Caceres had been assassinated – to say those words was to feel as if a rock were hitting me.”

The reality of her death also reminded him just how precarious life can be for activists in Honduras. But he said he can’t let fear rein him in.

“Don’t get me wrong,” he said. “I want to live. I love life, but I don’t want to be always protecting myself.

“I’m careful. I don’t go out at night. I limit my activities to some extent,” Melo said. “But I want to continue trusting, and enjoying my freedom.”

That trust, and everything else that keeps Melo busy, dovetails with his spiritual life. “For me,” he said, “spirituality is bathing every daily action with God. There’s no dichotomy between the spiritual and what we do each and every day, whether I’m eating pork rinds or at a meeting or saying mass.

“Whatever I’m doing, if it’s infused with spirit, then it’s more than material,” he said.

That’s the way he approaches working for justice in Honduras.

Click here to read the story and listen to the interview at spiritualedge.org.

Maria Emilia Martin is a journalist fellow with the Spiritual Exemplars Project.