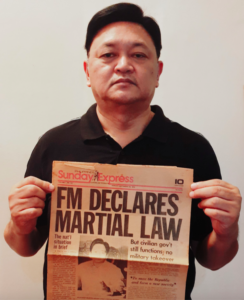

Nester Castro (left), professor of anthropology at the University of the Philippines, holding an English-language Filipino newspaper from 1972, when Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in order to secure his grip on power.

“My brother joined the communist guerrilla movement in the Cordillera in 1974,” Castro said when we met at a coffee shop in Manila’s Makati district–with its shopping malls and posh hotels, a spot as unlike the simple villages of the Cordillera as any other in the Philippines.

“He was arrested in 1975,” said Castro, who related his remarkable stories with a social scientist’s wry detachment. “When he was in prison, his comrades were contacting me, asking me to deliver messages. So when I graduated, I went full time into the underground movement, organizing students.”

The leader of the indigenous movement opposing the Chico River dam project was Macli’ing Dulag, a chieftain of one of the tribes that initiated the peace pact initiative between the Kalinga and other Igorot groups. Dulag soon gained national fame as the voice of the Marcos opposition among the mountain people of the Cordillera.

Castro met Dulag and spoke of him with great respect.

“People from the National Power Corporation came and said to Dulag, ‘Why are you opposing this project? You don’t even have papers to show that you own the land,’” Castro recalled. “And his response was, ‘How could a piece of paper own the land when it is the land that owns us?’”

In 1980, Dulag was killed by a paramilitary group loyal to the Marcos regime. Castro himself was arrested, imprisoned and tortured by the regime in 1983.

Castro said that the syncretistic Catholic culture of CICM, the Belgian Catholic order that took root in the Cordillera during the early 20th century, accommodated left-wing resistance to dictatorship as easily as it incorporated indigenous ritual into the Catholic mass.

“When I was in the underground, we would hold meetings in CICM facilities,” Castro said. “And when I was a prisoner, Belgian priests visited me and gave me a gift of a cooking stove because they heard that there was not enough food for the prisoners.”

Return to “Sapi’s Struggle.”

Nick Street was a senior writer with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.