By Addison Baker

Addison Baker is an undergraduate student at The University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. Addison spent time researching the Black Lives Matter movement, along with healing modalities and spiritual practices used by the movement, alongside CRCC’s Hebah Farrag. Baker won a student research grant and spent the summer of 2021 researching healing justice organizations and the virtual intersections of religion, environmentalism and social justice at Dignity and Power Now, a nonprofit organization in Los Angeles, CA. This blog is a reflection of her experience as a student researcher in BIPOC healing justice spaces.

Two years ago this month, Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old frontline medical worker, was murdered in her bed while trying to sleep. She was killed by law enforcement executing a no-knock warrant in Louisville, Kentucky. Two years later, many organizations and social justice activists continue to work on the frontlines of dual pandemics: state violence and COVID-19.

It’s a powerful experience to witness the resilience of a community in the face of these traumas. And if there’s one word to describe the advocates, organizers and community members at Dignity & Power Now (DPN), it’s “resilient.” Established in 2012 by Black Lives Matter (BLM) co-founder Patrisse Cullors, DPN is at the center of the healing justice movement. As a Los Angeles-based grassroots abolitionist organization, their mission is to fight for the dignity and power of all incarcerated people, their families and their communities.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, community members in the organization have participated in digital healing justice spaces. During the summer of 2021, I worked with DPN as their remote Health and Wellness Program intern. As an outsider to the community, I bore witness to the trauma and loss of community members impacted by police violence and incarceration. Through the ethics of deeply listening and holding space, I experienced the incredible resilience of the organizers, advocates and community members at DPN and the power of healing justice.*

Addison created the following poster for the the University of Puget Sound’s 2021 Summer Research Symposium:

Healing justice” is a term coined by Cara Page, a Black queer woman, to describe a movement created by queer and trans people of color to combat the burnout and ableism ingrained in social justice work—challenges that are amplified by the lack of access to quality healing services and health care in marginalized communities.

Organizations like DPN see healing justice as completely intertwined with their social justice work. Healing justice’s spiritual and community care principles work to support communities directly impacted by state violence. Healing justice also pushes back against individualistic and Western notions of “self-care”—from manicures to massages—that commodify healing practices for the sake of profit. Healing justice centers Black, Brown and Indigenous healers and reclaims appropriated practices, such as smudging, to cultivate community healing.

Healing justice intervenes on trauma and violence by providing individual and collective care in the forms of counseling, reiki, acupuncture, yoga, plant medicine, somatics and many other practices. As queer disabled writer and healer Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha writes, “If it’s not centering Black/Indigenous/people of color (BIPOC) healers, it’s not healing justice. If it’s not affordable, it’s not healing justice.”

Healing justice also encompasses a multitude of spiritual and religious practices from different cultures. One spiritual tradition in particular, Ifá, is a Yoruba faith and divination system practiced by Patrisse Cullors (founder of DPN and co-founder of BLM) and Leah Penniman, author of Farming While Black. Both Cullors and Penniman are ordained Ifá practitioners. Penniman is a farmer and food sovereignty activist who connects food and healing justice to Afro-Indigenous religious practices. In DPN’s virtual healing justice spaces, community members are able to reclaim spiritual traditions such as Ifá, which are frequently demonized in Christian culture, in an effort to own their stories and connect to their ancestry.

DPN has adapted to combat the greater stress on a community made even more vulnerable by the COVID-19 pandemic. The organization’s ability to quickly adjust to new needs is exemplified by the creation of their COVID-19 Emergency Relief Fund. The fund provides essential supplies, such as personal protective equipment, COVID testing kits, emergency food, household goods, clothing assistance, baby necessities, and rental and financial assistance.

DPN staff also moved their work onto Zoom and cultivated engagement on social media such as their Facebook and Instagram profiles. Digital work through the Health and Wellness Program helps the community grapple with losses caused by the hardships of state violence and COVID-19. Through my work with DPN, I identified how healers virtually facilitate connection to nature, spirituality and activism, and how this connection allows participants to claim their stories, develop sovereignty over their bodies and empower their community.

A central part of my work as an intern was planning for family meetings. Held once a month on Zoom (and in-person before COVID-19), these meetings were created for individuals and families in the Los Angeles area who had suffered the loss of family members at the hands of police violence. In these meetings of around 25-30 people, DPN staff offer a space—even if one mediated through Zoom—where individuals can share their trauma and be guided through a healing practice by a guest healer.

In addition to holding family meetings, the Health and Wellness Program works with healers to put together informative videos about accessible healing at home during the pandemic. For instance, DPN healer Thanh Mai created a video on plant medicine for grief and stress that was posted on DPN’s Instagram and Facebook accounts in July 2021. In the video, Mai shares Indigenous plant knowledge to inspire community members to connect to the nature that is around them.

Police violence, incarceration and COVID-19 create challenges for marginalized communities that prevent them from connecting to nature. Each causes physical and psychological harm that alienates individuals from the environment around them. Healing justice seeks to create spaces of solace from harm by connecting communities with tools to exercise autonomy over their bodies and reclaim their relationship to nature.

From DPN’s lens of Afro-Indigenous spirituality, nature is valued as kin, and one is to live lightly on the earth. This ethic embodies the values and practices of nepantla environmentalism. This kind of religious environmentalism challenges the dominant perspective of white progressive activists who view nature as separate from themselves, a mark of Enlightenment thinking. DPN’s work cultivates decolonial environmentalism, which takes into account how race and class affect experiences of nature.

Watch CRCC’s 2016 video about Dignity and Power Now

In addition to nature and spirituality, DPN sees healing as inherently attached to social and political engagement. At DPN, the Health and Wellness Program exists directly to combat the “martyr mentality,” the idea that activists should give all of themselves to the cause. The program also provides trauma care rooted in community engagement. Michele Ynfante, Senior Campaign Lead at DPN and founder of the monthly family meetings, discussed in a debriefing session how families have to be their own investigators when it comes to police violence and incarceration because no one will help them figure out what happened to their loved ones. By getting involved in coalitions that support them through their grief, families narrate their own stories and find solace in the fight for justice. For this reason, DPN’s Health and Wellness Program is completely entwined with their Activism, Coalitions and Leadership Programs.

The power of DPN’s healing justice extends far beyond just one community. My experience doing ethnographic and intern work with DPN required me to deeply listen to and feel the discomfort of devastating experiences of racial trauma and violence. While the healing I observed and resources DPN provided to community members were powerful, pain and grief were still palpable in every space without a clear solution or quick fix. I came to see my role in these spaces as bearing witness.

In this way, DPN’s work creates a broader reckoning when others outside the immediate community are invited to deeply listen and hold grief together. To acknowledge and honor the suffering of another person is important because it recognizes our shared humanity—that we are not separate from each other. In the words of Jewish and queer healer Dori Midnight: “My body is made of stars and dirt and the blood of my ancestors and the breaths of all the people who have been here before me and the green exhale of the trees. How can I possibly think my pain and my joy is mine alone?”

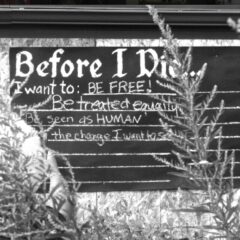

Breonna Taylor’s death, other instances of state violence and the COVID-19 pandemic have created overwhelming pain for communities and activists. My time working with DPN taught me not to hide from the pain, but to confront it and feel the weight of it together, in community. Healing justice creates the tools for healing within communities and asks for the space to share pain and be deeply listened to. DPN embodies one model for healing justice, that endured the test of the pandemic, and may allow communities of color to get the rest that Breonna Taylor deserved.

* My presence as an outsider in the community was rooted in the practice of “speaking with” others and striving to create the conditions for dialogue, as Linda Alcoff’s essay “The Problem of Speaking for Others” discusses. My work was also guided by Robin Wall Kimmerer’s insight in her book Braiding Sweetgrass and her idea that “experiments are not about discovery but about listening and transplanting the knowledge of other beings.”

Photo by FloNight (Creative Commons)