How spiritual exemplars work to create a world befitting of our inherent nobility

A key question we are asked by consumers of our research on “spiritual exemplars” is about the qualities of this group of extraordinary humanitarians. What allows them to do what they do? What makes them unique as a global peer group? Do they embody some special quality that others can learn from or emulate?

Though we’ve grappled with lists of personality traits and qualities, and we have tried to identify key turning points within their life trajectories, the one thing that has dogged us throughout the project is the way that so many of our exemplars hold within them a special tension or paradox.

While our exemplars are extremely different, and they draw on different spiritual tools working in radically different contexts, this same paradox emerges in so many of them that it cannot be ignored. It is the coexistence of radical resistance and radical surrender.

On the surface, it seems like these two things should not go together. Our exemplars demonstrate a superhuman form of grit. In the face of extreme poverty, oppression or environmental destruction, their tenacity and commitment to the change they wish to see in the world is unparalleled. They are in so many ways unstoppable, acting in deep love for the communities they are a part of, refusing to accept the status quo, swimming upstream and taking immense risks that many of us could never imagine.

And yet, at the same time, they embody a pervasive spirit of surrender and acceptance. They seem to have the ability to simultaneously hold fast and to let go, to dig their heels in and to flow.

This tension within individuals parallels another: Our exemplars live and work in some of the most difficult contexts in the world, yet so many of them are effervescent in the peace and deep joy they emanate. It feels welcome — like a breath of fresh air — but out of place given their daily experiences and the struggles of the communities they work with.

To be certain, the toll the work takes on exemplars should not be minimized. They experience burnout, illness, strained family ties, vicarious trauma, and even torture and threats to their lives. Still, their ability to continue their work over so many years, to remain deeply committed to their communities, and to exhibit joy and seemingly limitless flows of love is mystifying.

Are they superior beings, or is there something that happens within their work itself — a clear relationship or process that unites these apparent opposites?

To understand the coexistence of radical resistance and radical acceptance, it is important to look at how exemplars experience their own lives and work, and how their spirituality operates for them on the inside. For example, Tom Catena, a doctor working in Sudan, says people always tell him, “Gosh, you are a masochist!” But, internally, he doesn’t experience it that way at all.

Immigration advocates Sister Pat Murphy and JoAnn Persch, now in their 80s and 90s, embody that spirit of grit and tenacity over many decades of their lives: “It’s hanging in, and being persistent….It’s going back respectfully and peacefully….But we never take no for an answer.”

That perspective has landed them, and a number of other exemplars, in jail. Their response is to let go and to flow: “That would [be] okay if I stayed in jail for a while….We’d just start a new ministry. We’d know that’s where we were supposed to be right then.”

As exemplars describe this process of letting go even in the midst of their resistance, they use words across their different spiritual traditions like “complete trust,” “surrender as a form of salvation,” “freedom from the bondage of things,” and “letting go.” So between radical resistance and release, what happens?

One dynamic we see clearly in their lives is a reciprocal relationship between their work and their spiritual practice. As spirituality and spiritual practice grounds our exemplars and gives them strength, so too does the hard work itself deepen the practice and their spiritual orientation. At some point, they become inseparable — in fact many exemplars could not articulate a separation between their work and practice.

Many of them take enormous time in their spiritual practice — from chanting, to prayer, meditation, rituals and even shouting into the void. Some take month-long retreats, others rise at 3 am to begin their daily ritual. A key force that drives them into practice, and informs what happens in that space, is precisely the very difficulty of the work they are engaged in.

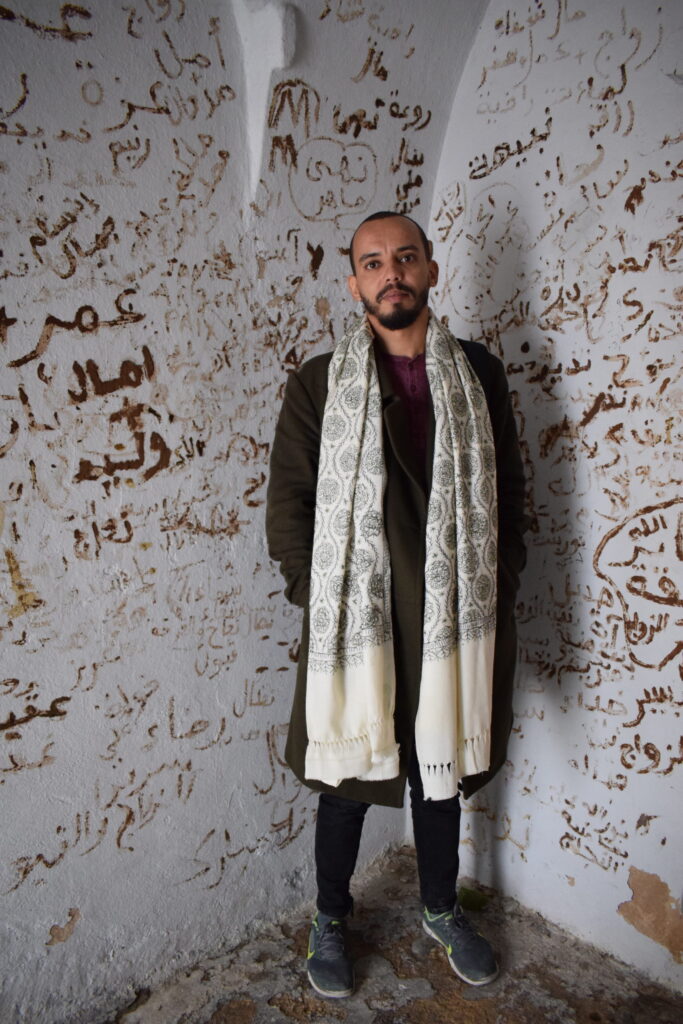

Badr Baabou, a human rights activist in Tunisia, explains of his daily life, “I’m being chased constantly, my cell phone is always stalked.” Others bury the children and youth they work with regularly. Sameer, a peace activist, speaks of the difficulty of being in a space in which Palestinian homes are routinely demolished, there is pervasive killing, “and all of this tension” around him and within him.

That difficulty drives our exemplars into spaces that Julie Coyne describes as “forced surrender.” “Let’s put her in a situation where it is so far beyond her ability to fix that she will learn to let go,” she jokes. Sameer explains that when things are so difficult, when he feels everything they are doing in the struggle for human rights is useless, he goes to the Wadi: “I like to sit there and scream and hear the echo around me. It feels like letting go. It feels like releasing.”

Hear Sameer perform his ritual of screaming into the desert

Others working in extreme contexts, like Archbishop Jacques Mourad, who was held by ISIS in Syria, offer a prayer of surrender every day: “I abandon myself into your hands….I am ready for all, I accept all.”

It is clear that exemplars’ work contexts — whether due to the physical or emotional demands — are pressure cookers that nudge them over and over toward spaces of radical release and surrender. And as longtime, dedicated practitioners, they have trained their hearts in a discipline of spiritual grounding, to create and inhabit the “architecture” of spaciousness within them in which the magic happens.

Within spiritual rituals and practices, exemplars experience many things. Across traditions, they use language like catharsis, surrender and letting go. Many speak of quieting their ego or stilling their heart to receive new insights that are later put into practice in community. Deep renewal, joy and peace exist with this drink, with this exhale, with this quiet listening. There is a remembering, a growth or an affirmation of purpose. They are in the right place and the right time, they don’t need all the answers, they have deeply accepted their role, not as a savior, but as a vessel for love and humanity.

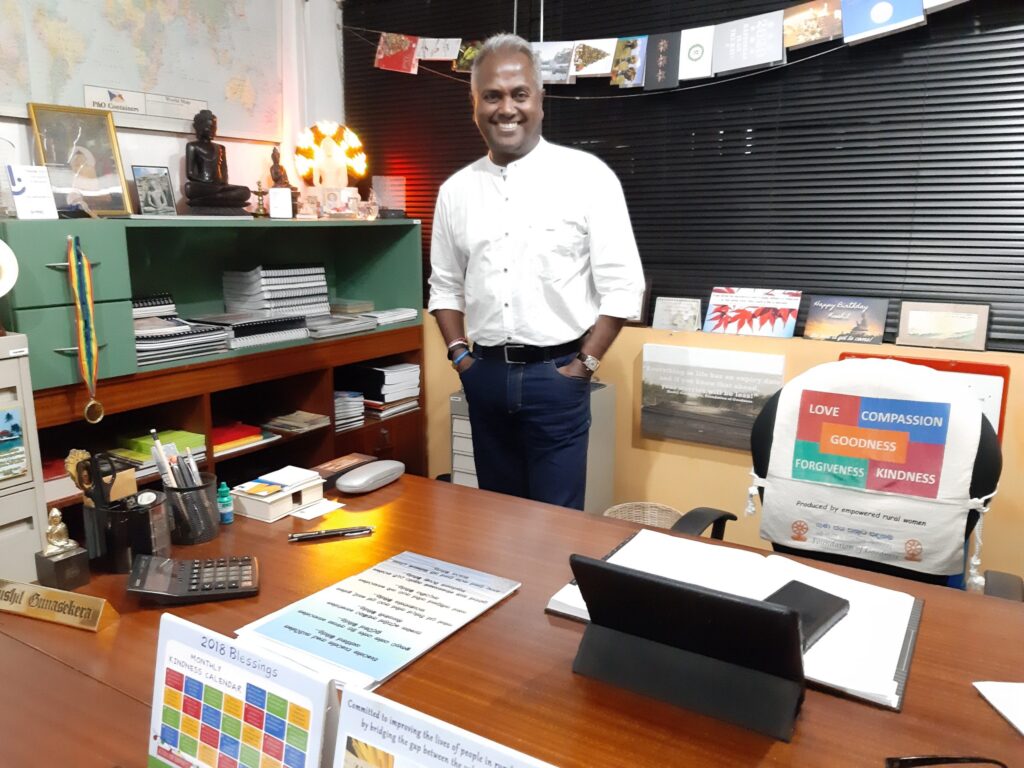

“It’s unshakable bliss. Peace begins when the expectation ends,” says Kushil Gunasekera, a Buddhist humanitarian in Sri Lanka.

“Someone asked me the other day, ‘Tom are you happy?’” Tom Catena says. “Happiness is an emotion which goes up and down. Joy is something you have deep inside you. Joy means you are in the right place.”

After these rituals of renewal, our exemplars go back out into their work in what could be called a kind of avatar state — with more strength than ever and with an acceptance, flow, freedom and vibrant love they bring into their projects. While burnout and physical toil should not be ignored, this process helps make the work more sustainable and focused. And it doesn’t end there.

More grounded and nourished, many exemplars go back into the work as a spiritual practice. Each conversation, each action, each hard decision is treated as part of the practice, continuing to strengthen the muscle of spirituality itself, allowing them to meet each difficult moment. Work as a spiritual practice alone might not be enough, but coupled with the quiet worship or meditation time, there is renewal, resolve, soul expansion and invigoration.

The spiritual work done in retreat and early morning rituals could be described as more vertical, private or internal work. But as exemplars move back into their day, that spiritual fire is flipped horizontally into the laboratory of the community, and it becomes relational.

All day, in interpersonal exchanges with staff and with the people nurtured in their programs, sacred exchange is at play between humans. A flow of love and energy moves within their project, with the exemplar serving as a key vessel or reflector, both giving and receiving that love and energy.

From our exemplars, Indigenous, Catholic, Buddhist, Muslim:

“The sacred and the divine are the very human things of life; human connection is divine and sacred.”

“There is a oneness.”

“There is an intimate exchange.”

“We see one another’s inherent nobility.”

Oneness, that recognition of inherent dignity and connection, can’t be unseen by exemplars or their staff. It can’t be unknown. It is a constant relearning that comes directly from the people they work with. The work, then, is to preserve, to nurture, to learn from and to liberate that dignity over and over again.

As ordained Ifa practitioner, artist and abolitionist Patrisse Cullors has put it, “The fight for life is a sacred fight.”

In the pressure cooker of intractable conditions, exemplars fine tune their vessel, opening themselves to share and receive sacred insight, sacred light. Accepting what is before them as it is, they resolve again and again to create a world, small or large, befitting of the inherent nobility of those who inhabit it.

Explore map of spiritual exemplars around the world

Arpi Miller is an affiliated scholar with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.