Abstract: Competing voices within spiritual groups help to create boundaries of belonging within and beyond the group by articulating notions of identity and meaning that are based in history, myth and gender, among many other factors. Hebah Farrag’s article, “The Spirit in Black Lives Matter: New Spiritual Community in Black Radical Organizing,” in Transition, Issue 125, 2017, pp. 76-88, Published by Indiana University Press, focuses on locating these competing voices in the African American community following the emergence of the #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) movement.

This article seeks to bring to light the ancestral spiritual practices nestled within a political movement. It also highlights the process in which the creation of spiritual community has been often missed or ignored in lieu of a focus on violence and dissent. BLM chapters and affiliated groups have employed a variety of spiritual practices to generate meaning, heal trauma, combat burnout and encourage sustainability in their organizations. This along side with a notion called “radical inclusion,” has centered marginalized groups within the movement and has worked to disrupt a legacy of Black leadership that is largely hetero-normative and almost exclusively male. This article also seeks to bring to life African traditional beliefs and other spirit focused practices used by BLM to heal the sickness of violence ravaging Black Americans.

***

In November 2014, Evan Bunch graduated from American Baptist College in Nashville, Tennessee and moved to Los Angeles, California to work as an organizer for Dignity and Power Now (DPN), a grassroots organization founded in 2011 by Patrisse Cullors. Patrisse, by then, was also the co-founder of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, which had catapulted to the fore of American consciousness, altering the fabric of radical organizing and igniting a conversation about race that would travel across the globe.

Evan grew up poor, one of seven, raised by a single mother in Jefferson, Ohio, “a very small country town, where the cows moo,” he describes. If you ask him, he will tell you that he was raised in the “Black Baptist Church tradition” but when you text him, he responds with words like ‘Ashé,’ a Yoruba term often used by practitioners of Ifá, a faith and divination system that originated in West Africa.

In June of 2015, Evan participated in what news outlets dubbed a ‘protest’ in front of the home of Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti. Evan, like many of the other participants that gloomy morning, saw this action not as protest but as a ceremony. The action came as a response to the exoneration of two Los Angeles police officers responsible for the brutal killing of Ezell Ford, a mentally impaired young homeless man, shot in the back while on the ground, in August 2015.

If you click through the Los Angeles Times article on the ‘protest’ you will see video of Evan singing an African American spiritual, ‘I Shall not be Moved’, but that is not what he remembers about the morning. Evan remembers participants arriving to the Getty House, the official mayoral residence in Windsor Square, many dressed all in white, a custom often required in many traditional Ifá ceremonies. He remembers joining hands and the power of prayer, though not in the way one might expect.

“We did an Ifá ceremony in front of his house, ” Evan begins, “the preacher, I guess he was the facilitator of the ceremony…he was able to conjure up Ezell Ford’s spirit and kind of transfer it to the group. And it was evident through the participants that they were feeling something that was not of the temporal world.” There in historic Hancock Park, amidst calls for justice, divination had occurred and Evan began to see faith differently.

“It’s inexplicable, of course,” he explained, “however, it provided confidence in that moment. Ifá is a faith of not only just ancestors of African slave origin…It was our spirituality before we became a broken people here in America and with Ifá, [practitioners gain] the strength of their ancestors.”

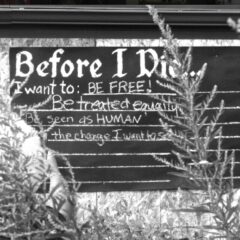

The #BlackLivesMatter movement tends to invoke images of Ferguson, statements like “I Can’t Breathe,” or perhaps the list of hashtagged names that grows larger every 28 hours. What is generally missing from these depictions are images like the white-clad Black woman burning sage across a militarized police line; documentation of the chants in front of the Los Angeles courthouse declaring “summon our ancestors,” and grassroots organizations’ use of spiritually infused tools to heal those directly impacted by state violence.

Evan is one of many organizers involved in DPN and more broadly BLM, who have begun to reinterpret African spiritual practices and beliefs, embracing ancestor worship, Ifá based ritual such as chanting, dancing, and summoning deities, along with healing practices such as acupuncture, reiki, therapeutic massage and plant medicine for a variety of personal and professional functions.

BLM chapters and affiliated groups like DPN have been blending a variety of spiritual practices to impart meaning, heal grief and trauma, combat burn-out and encourage what is called transformative justice in their organizations. Transformative justice, an abolitionist philosophic orientation to peace-making and community accountability emerging from the Quaker tradition, sees harm within in a continuum of experience, offense as an opportunity for education and crime as a community problem to be solved through understanding. The BLM network has also employed a ‘radical inclusion,’ embracing female and queer leadership along with members often shunned and/or marginalized by traditional Black faith groups, thus disrupting a legacy of Black leadership that is largely hetero-normative and almost exclusively male. In this process, a new spiritual community has been created, which observers have largely overlooked.

***

Jayda Rasberry grew up in Los Angeles as one of six siblings in a large family. She became an organizer at DPN in 2014 after spending six years in Valley State Prison for Women. Jayda endured medical neglect while in prison which significantly impacted her health. Jayda is also Black and queer.

I spoke with Jayda at DPN’s regular health and wellness clinic hosted at Mercado del la Paloma in the Figueroa Corridor of South Los Angeles, a neighborhood that has historically suffered from disinvestment. Housed in a converted garment factory, The Mercado is a community gathering space dedicated to economic revitalization, hosting the DPN office along with dozens of other non-profits on its second floor, and a bustling market filled with local vendors and programing space promoting arts and culture on its first floor.

This spiritual health fair uses this community space to provide what it calls “wellness and resilience,” to those directly impacted by state violence and their families along with community members free of charge. Within this space an assembly of healers gather. Acupuncturists, reiki practitioners, herbalists, those trained in somatics, massage therapists, aroma therapists, art therapists, practitioners of theater of the oppressed, tarot card readers; each with a table and a line. Each of the practitioners here donate time to serve people because they believe trauma, pain, and historical violence is a sickness trapped within the bodies and spirit of those impacted by violence. The introduction of holistic healing practices to communities directly impacted by state violence serves a direct purpose: empowerment. For those who have embraced this broadened perception to health, spirit, body and mind, the orientation seeks to create a mindset towards liberation, connecting environment to harm and allowing for agency.

It is within this colorful overflowing space, bustling with conversation, candles, pungent aromas, and laughter, that Jayda tells me her story.

“I never thought I would find a family, I mean other than my own and they have to because were blood, who would take me in and DPN, they really took me in like family. With all my flaws and with open arms. They all really cared about the traumas that were stopping me, telling me constantly, ‘Jayda, you matter.’ Most organizations, people really, would throw someone like me to the side and say, ‘wait, you have a lot of baggage,’ with DPN they say, ‘we see you and we see something in you.’ Something that often I didn’t even see in myself, you know.”

Jayda explained to me that the three pillars of DPN were abolition, transformative justice and healing justice, each working together to help enable community resilience, growth and revitalization. “Healing is important to each aspect of our work,” she explained, “it is integral to the social justice movement. There is a lot of trauma that comes with us in our work, we have to make sure we are okay, to make sure our community is ok.”

When asked to describe what being okay looks like, Jayda tells me, “As a formerly incarcerated person from a directly impacted community, I was never taught about eating well, about acupuncture, about herbs, about how stress affects the body. In order for me to able to do the work that betters my community, I have to learn about wellness. Spirituality and healing has to be at the forefront.”

For those working in organizations like DPN, this organization becomes more than work, it becomes family, future and a way of life. DPN’s radical inclusion, an openness and transparent nature that often comes in stark contrast to the portrayals of protesters as angry and vengeful or hateful and violent, is one of its defining markers.

“You are welcome in any way that you are,” Jayda emphasized to me, as so many before her, “Heterosexual, Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, transgender, gender nonconforming. We accept everyone. We all have different outlooks, we all have different traumas, and we work to revamp everything to make everyone comfortable, we never just exclude because that is another form of trauma.”

Violence, whether at the hands of the state, law enforcement or the church, is often a topic at DPN member meetings; meetings that begin with introductions that ask participants to specify preferred gender pronoun or PGP, a prayer adapted from Assata Shakur’s Letter to the Movement, and hold space for attendees, a term used to indicate creating a zone free from judgement and harm, to discuss what they are carrying in their spirit at the time. For as often as DPN programs, clinics, protests, and panels become ceremony, they also become therapy. Meetings, clinics, protests at city hall and town hall meetings, successful campaigns, programs at prisons, conferences on women’s issues, all are included as part of the collective healing from state violence as well as personal rejection from within the community. As Jayda says, for many that attend health and wellness clinics, often times scheduled Sunday mornings, DPN has become church.

Mark-Anthony Johnson, Director of Health and Wellness, describes it in this way:

We try to have a wellness component to a lot of our meetings…the unfortunate thing is a trend where wellness and thinking about care is thought of as something you do outside of movement work… you take care of yourself outside of the office type of thing, but I actually think it’s necessary to pull that into the work. And for me that’s where the connection is made around spirituality. Right? It’s like wellness, mental health, spirituality, they all overlap in a really intimate way, and so I think it’s critical for work.

The infusing of spirituality into Black radical organizing is intentional if you ask Patrisse Cullors.

Patrisse grew up as a Jehovah’s Witness, but left the religion at an early age. “I think some of the things that impacted my… ability to feel peace at the Kingdom Hall was that at any given moment the elders, which were all men, could decide if you were going to be disassociated in the fellowship from the Kingdom Hall”

Patrisse is well aware of the toll spiritual violence has had on specifically queer people of color.

As a queer Black woman, Patrisse went on to continue her search to “feel deeply connected to spirit and the universe.”

Patrisse found a new faith in Ifá but not before facing continued discrimination for her sexuality when her initiating babalawo (priest) refused to initiate her, requiring her to find an alternative.

“I practice Ifà. Ifà is my spiritual home,” she describes, “but I’ve done ten day Vipassana retreats. I’ve done all types of spiritual quests. I have a deep practice of generative somatics. I have a meditation practice. I go to therapy. I exercise. I’m actually doing a juice cleanse for the next few days. So I’ve learned a lot from the last fifteen years about health and wellness.”

For Patrisse and many others in DPN and BLM, their faith resembles the Mercado, remade from spaces of trauma and theft, into an assemblage of healing tools used to promote equity in a united commitment to sacred respect. And while each person may have their own primary practice, their ‘spiritual home’, each person also feels welcome to engage any of traditional practices and modalities at the Mercado and are comfortable using a broad range tools to reach peace.

“I think it’s an everyday journey, like, every single day is a new day to be present for my aliveness,” Patrisse emphasizes this when discussing her spiritual rituals and beliefs. ‘Being present for my aliveness’ is in and of itself a radical statement for Black Lives Matter organizers. Being alive, is in and of itself an act of resistance to Patrisse. In this context, healing from incarceration and state violence, living a healthy life, coping with histories of violence and working to be a whole spiritual being becomes not only a personal act of defiance but an organizational act for the movement, an act that at once fortifies the self, the spirit and the work.

“I think I’ve learned this from Audre Lorde, and then bell hooks, and then from Generative Somatics, and from Lisa Abrigiando, from Lisa Perry, from Black women, from Black queer folks in particular,” Patrisse says. “My living actually is a form of resistance. My being alive and being courageous about how I live, which is really healthy, exercising, very rudimentary things that are essentially taken from us as black folks in particular. To reclaim our bodies and our health, is a form of resistance, a form of resilience.”

***

If you ask anyone in DPN or BLM, the “healing justice networks” are growing. Groups such as Generative Somatics in Oakland, CA, Harriet’s Apothecary in New York, Social Transformation Project and Black Organizing for Leadership & Dignity (BOLD), all of which use a variety of alternative practices, such as somatics, alternative medicine and psychoptherapy, as tools to transform and empower individuals.

One reason for this growth may have to do with a key shift in ideology. DPN actively works to dismantle martyr mentality, an ethic where activists, humanitarian workers, community organizers and volunteers burn out by devoting themselves almost entirely to the cause. DPN uses a language focused on self-care to advance the opposite notion—that you must take care of yourself first. It has also worked to flatten its organizational structure, leading to it often being dubbed a ‘leaderful’ movement, in stark contrast to its depiction as ‘leaderless’.

This perspective is evident in the structure of Dignity and Power Now (DPN), which aside from employing, training and providing therapy to those directly impacted by state violence, has a paid Director of Health and Wellness, a position often seen within a church but not often within a non-profit organization. Patrisse calls the creation of the position a political choice:

The Director of Health and Wellness is both for the health and wellness of the organization and the people in it, but also it’s the health and wellness of people who participate in our organization and participate in building this team of people that can really help support a different narrative about what we are supposed to be doing in the world. It’s not just about changing policy, it’s not just about changing lives, it’s about changing our culture and it’s about changing how we fight. So we can change policies all day but if the fight to get there was full of trauma, was replicating oppressive dynamics and abusive dynamics, then what is the point? What is the real point of the work that we do?

This call, to work to replace oppressive dynamics, not only in the criminal justice system or between law enforcement and the black community but also within organizational structures and religious practices that emanate from inside the Black community, has appealed to many.

Mark-Anthony Johnson, director of health and wellness and a founding members of DPN, was born and raised in Los Angeles. Mark-Anthony was raised Christian and then practiced Judaism with his family until being introduced to Ifá in his early twenties.

“I wouldn’t say that we’re a religious organization but we have spiritual conversations all the time,” Mark-Anthony says, “We’re always having conversations around how this work and abolition work is very much de-colonial work, and spiritually de-colonial work. Right? Like what does it mean to be black folks in a colonized context and what does that do to your spirit?”

For Mark-Anthony, the response to the historical violence carried by directly impacted communities is a philosophic framework. “I think for me, having an explicit, or implicit spiritual framework that is rooted in the traditions of our folks is really important to healing from incarceration…it’s actually really important, because of just how much that trauma is ubiquitous in some way.”

He provides the following example, “in Yoruba spirituality, and Ifá, there’s this concept that everyone has a destiny, everyone has some meaningful purpose in the world,” he continues, “…(and) mass incarceration is one of the biggest assaults on our purpose…when you talk about a system that’s systematically targeting black and brown folks in a way that it’s restricting freedoms, restricting people’s access to their own self-determination, that is restricting people’s access to a sense of purpose and a sense of, the ability to do meaningful work in their own lives, I think that’s a spiritual question. And I think it’s a spiritual assault in some ways.”

Mark-Anthony uses a faith-infused framework, based in African and non-western spirituality to try to create new and what he views as healing narratives, which both disrupt narratives of inferiority and work to provide agency, it also gives voice and acceptance to those that don’t fit within traditional philosophic frames around morality, good/evil and punishment.

Mark-Anthony is also a licensed acupuncturist and substance abuse specialist, who came to these trades after Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. Acupuncture to Mark-Anthony is a way to impart immediate relief to those in pain. “I was really inspired by this idea that you could impact someone’s mental health via a physical modality such as acupuncture,” he discusses at length, “I was looking for a bridge and another resource to address people’s immediate trauma. Because I had these other broader questions, if mental health is this spiritual context and there’s all this violence happening to us on a mental health level, on a spiritual level, how can we influence that. So acupuncture became my solution.”

Mark-Anthony, while directing policy, providing care for team members and community members, and campaigning for no new jails, also does acupuncture on site. “At DPN we make it a point to know that trauma is always in the room,” he explains, “particularly for folks who have experienced state violence or have been incarcerated, it’s a very real thing. We have some our campaign leaders who’ve been brutalized by sheriffs and at the same time are going to meetings with sheriffs, in uniform, and speaking truth to power, and [have] PTSD…there’s a place in which I think there’s this intersection in terms of thinking about spirituality on a very basic level of just access to purpose and feeling purposeful, and it’s hard to do that and, when you’re having flashbacks of how you were being brutalized…So, acupuncture is a really effective way to soothe that.”

How do those brutalized by a system, gain the personal power to fight the same system that traumatizes them? How do they do so without replicating the same systems of oppression they are attempting to overcome? Black radical organizers have asked these questions for generations and for DPN and BLM, the answer is simple, heal the self, change basic relationships fundamentally, create just organizations built on equitable leadership and give people opportunity and possibility to imagine and the future will emerge. When trauma, brutalization, denial of purpose, and loss of community are discussed, their container allows the target to move from state violence to member disputes to mindfulness practices, it allows the focus to move from outside, to within, from past to present, from history to future.

“For me, spirituality has the ability to support one’s safety, has the ability to support one’s resilience,” Patrisse explains, “I say the ability because I don’t believe all spiritualties do that. There are many spiritualties that further repress and subjugate people in their communities, but I’m calling for spirituality to be deeply radical in its ability to heal people. I don’t think we’re people to be fixed but rather how do we hold faith for people who’ve had harm caused to them in a way that makes them feel like they have agency again? That’s what spirituality has the ability to do.”

In DPN and largely in BLM, spiritual tools are remade, and often divorced from their traditional contexts, in order to be used solely to heal, revive, rebuild and create community within groups often marginalized by mainstream religion.

Given the zeal with which many mainstream black religious leaders have criticized Black Lives Matter, it is no wonder why many BLM supporters feel alienated. Organizations like ultraconservative Staying True to America’s National Destiny (STAND) have issued statements calling BLM “divisive and demonic.” Pastor J. Edgar Boyd of First African Methodist Episcopal Church — the oldest black congregation in L.A. — was quoted as saying BLM was “is a tremendous force that is … lacking of the kind of direction that it needs to have.”

Najee Ali, director of Project Islamic Hope called BLM ‘undisciplined,’ and said “they seem like a one-trick pony and all they can do is disrupt and make noise.”

In a interview with Krista Tippett on the radio show, On Being, Patrisse described the pain attacks from faith leaders have caused her and how that rejection has inspired their philosophic stance:

To be honest with you, so many of us in the Black Lives Matter movement have either been pushed out of the church, because many of us are queer and out. Many of us, the church has become very patriarchal for us as women, and so that’s not necessarily where we have found our solace. And I think we have had to contend with that during this movement. How do we relate to the black church and how do we understand ourselves in relationship to the black church inside of this movement?

But that hasn’t stopped us from being deeply spiritual in this work. And I think, for us, that looks like healing justice work, the role of healing justice, which is a term that was created probably about seven or eight years ago, and was really looking at how, as organizers, but also as people that are marginalized, that are impacted by racism and patriarchy, that are impacted by white supremacy, how do we show up in this work as our whole selves? How do we be in it as our best selves, and how do we look at the work of healing?

There are many voices from within the black church which have called for an acceptance and dialogue with BLM, or have even whole heartedly accepted and joined the movement. In Los Angeles, Pastors like Eddie Anders at McCarty Memorial Christian Church and Pastor Jean Marie Cue from The Row Church, have both joined and supported BLM directly. Yet, in each conversation where voices from within the black community vie for acceptance and space, a wall is placed between faith and BLM.

My question to you is, when we ask how the faith community can embrace BLM, why do we not also ask why we do not accept BLM as part of the faith community?

Within the space that has become known as Black Lives Matter (BLM), lives a religious experience and political ethic grounded in new notions of spirituality. These new notions are informed by and inform political ideas around organizing, activism, leadership development, organizational structure, and ultimately, political goals and motivations focused on state sponsored violence and historical trauma against the black community.

While this movement has captured the world’s attention, its nuanced use of spiritual language and targeted focus and healing and self-care in its organizational model has been over-looked.

There are many possible reasons why BLM’s spiritual work may be currently sidelined. Organizations like DPN employ tools from a very new tool box, namely, new spiritualties, which blend traditional African faith practice, such as Ifá and Santeria, with healing practices from what is seen as indigenous communities around the world. BLM and affiliated organizations have also worked to embrace all parts of the black community, including groups often shunned by conservative and mainstream Black religious’ groups, including the Queer and Transgender community, not only in its slogans and direct campaigning but among its leadership. This radical inclusion and focus on widening the scope and promotion of acceptance of the fringe has led to a tension between BLM activists and Black religious’ leaders along with a general fissure within the Black church over issues raised by the BLM movement.

The characterization of BLM movements as a disruptive, inexperienced, secular, leaderless movement has blinded many to the innovation, novelty and genuine invention that has been have given to the movement. Much of this innovation has centered around new approaches to spirituality and healing. While many have speculated that BLM has worked to secularize the new civil rights movement, instead, BLM’s marginalization of patriarchal and hierarchical modalities of religion has served to inform its members’ reinterpretation and expression of faith, political expression, radical organizing and community building.

Click here to read the full article on JSTOR

Hebah Farrag was the assistant director of research of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture through 2023.