From “pagan idols” to “avant-garde art,” over the course of the 20th century westerners have often evaluated the same non-western objects very differently at different historical moments. For the past three years I have been engaged in archival research about the intersection of art history and anthropology with an historical focus on the “social life” of what was once called “primitive art” and its display in western museums.

Although I did not initially conceive of the project as having a focus on religion, as I delved further into the 20th century history of the western transformation of items of material culture produced in non-western, primarily tribal societies, from their categorization as ethnographic artifacts to objects of fine art I found that the objects’ status as ritual or religious items was indeed significant. Since many of the objects that westerners consider to be “primitive art” come from societies in Africa, Oceania and the Americas, their provenience—who made them and when they were made—is unknown. This means that art dealers, collectors, and museums need to determine whether such an object is authentic or not based on a different set of criteria than that used by for western art.

Moreover, since many of the societies where tribal art is produced were formerly European colonies, at some point western missionaries had contacted most of them. When they first encountered these objects in the 18th and 19th centuries, especially things such as masks and statues used in various rituals or displayed in temples and other sacred places, the missionaries considered them to be associated with pagan practices and thus “idolatrous.” According to the missionaries, the destruction of such objects was a necessary first step towards the conversion of native heathens into Christians.

However, by the early 20th century, with the advent of avant-garde artists and intellectuals, the status of non-western sculpture, masks, and other ritual paraphernalia, began to change. Throughout the 20th century many museum curators and “primitive art” collectors based the authenticity of such art on whether it had been used in traditional religious rituals or was believed to have spiritual value to the people from whom the object had been obtained. Thus, an object’s spiritual value in one cultural context increased the object’s desirability, economically and aesthetically in its western context.

I will be presenting my Getty research as the Jensen Memorial Lecturethis coming May and June at the Frobenius Institute, Goethe University, in Frankfurt, Germany. The lectures have traditionally had a focus on some aspect of the anthropological study of religion and mythology. The lectures, titled “From Artifact to “Primitive Art”: The Inevitability of Cultural Commodification?” focuses on the historical and cultural dimensions in the United States of the transformation of objects westerners once thought to be pagan or heathen—and therefore either of no value or negative value—into valuable items of fine art, an event that happened relatively late in the 20th century with the decision of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to establish a Department of Primitive Art in 1968. I will demonstrate how the changing attitudes towards so-called “primitive art” both reflect and influenced changing ideas about race and religion in the United States.

Artifact to “Primitive Art”: The Inevitability of Cultural Commodification?” focuses on the historical and cultural dimensions in the United States of the transformation of objects westerners once thought to be pagan or heathen—and therefore either of no value or negative value—into valuable items of fine art, an event that happened relatively late in the 20th century with the decision of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City to establish a Department of Primitive Art in 1968. I will demonstrate how the changing attitudes towards so-called “primitive art” both reflect and influenced changing ideas about race and religion in the United States.

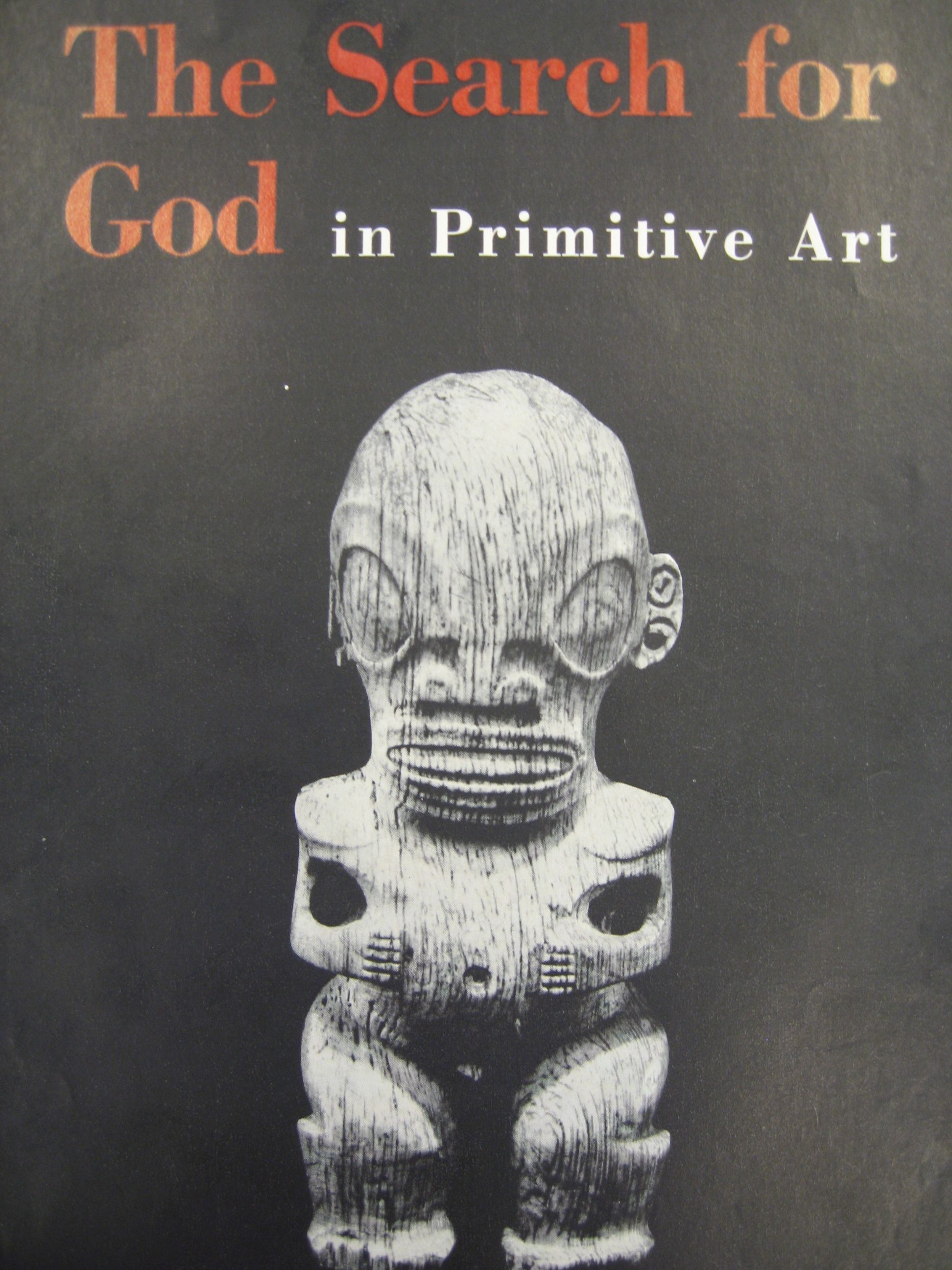

For example, in the archives of the former Museum of Primitive Art I came upon a review of the Museum of Primitive Art’s 10th Anniversary exhibit published in 1966 by the Board of Missions of the Methodist Church. The review was titled “The Search for God in Primitive Art.” It not only noted that much of the art in the exhibit was religious but that it represented “an attempt to translate myth and symbol, dogma and ritual, into earth and stone and wood.” It also recognized that “as we look at the way men have tried to express their religious beliefs, we may have a truer understanding of both religion and art.” How different these statements are from those of the London Missionary Society 150 years earlier!

Nancy Lutkehaus is a guest contributor with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.