For Rev. Najuma Smith-Pollard, the statistics that describe the plight of many urban AfricanAmerican communities aren’t abstractions— they’re everyday realities. St. James A M E Church, where Smith-Pollard serves as pastor, is at the heart of South Los Angeles. While problems like poverty and homelessness are acute, Smith-Pollard says that nowhere are her community’s troubles more apparent than in its high schools.

“Schools like [Alain Leroy] Locke and [ Thomas] Jefferson have an overall 95 percent drop out rate,” she says. “And half the kids in these school districts are foster-children, which means there are no parents around. Add to that the number of fathers who are in prison or in jail and you see the community is broken down on so many different levels. That’s why we need to push for programs that deal with re-entry for parents coming out of prison and that address gang violence, because that has become the new family for a lot of our children.”

Black churches like St. James have historically served as the primary reservoirs of social capital in African-American communities. But the tradition of advocacy and activism that reached its pinnacle during the civil rights era has gradually faded with the graying of the generation of leaders who came of age during the time of Martin Luther King, Jr. and activists like James Lawson—a key architect of the civil rights movement’s strategy of non-violent confrontation.

“At one time, social activism and social justice was the main message of the black church,” Smith-Pollard says. “I don’t think that is the message of most African-American churches today. Social justice action concerns are no longer necessarily on the front lines.”

This shift away from civic engagement reflects an inward turn among some African-American clergy and their congregations at a time when many black communities urgently need the kind of advocacy their religious leaders and institutions once provided. In a recent piece titled “Too Long Ignored,” New York Times op-ed columnist Bob Herbert notes a number of grim statistics related to black men in the United States: a third will spend time in prison at some point in their lives; those who die in their young-adult years are most likely felled by homicide; and less than half will graduate from high school on time.

“The aspect of this crisis that is probably the most important and simultaneously the most difficult to recognize is that the heroic efforts needed to alleviate it will not come from the government or the wider American society,” Herbert writes. “This is a job that will require a campaign on the scale of the civil rights movement, and it will have to be initiated by the black community.”

Thus recovering its legacy of passionate social activism in response to the challenges that Rev. Smith-Pollard and others like her are facing is arguably the greatest task the black church has faced in a generation. The primary goal of the Passing the Mantle Clergy and Lay Leadership Institute is to provide a spark to help reignite that flame.

“As a pastor I preach and I run the church,” says Smith-Pollard, a graduate of the first PTM class in 2006 and the current president of the alumni association. “But I also have to be engaged in what is going on in the community as well.”

The skills and networking resources Smith-Pollard acquired through “Passing the Mantle,” a program of the Center for Religion and Civic Culture at the University of Southern California, have enabled her to begin to develop Project Destiny, a series of interventions aimed at school-age girls, whose incarceration rates are increasing even more rapidly than their male counterparts. But perhaps even more importantly, she found in the program a kind of theologically grounded activism that honored the social justice legacy of the black church.

Finding a New Bottle for Old Wine

If helping African-American clergy and lay leaders reclaim that legacy seemed like an obvious way for the Center for Religion and Civic Culture to respond to the challenges facing black communities, the best strategy for shaping the PTM curriculum was not immediately apparent.

“In year one, we were still wrestling with where we were going,” says Rev. Mark Whitlock, director of the program and executive director of CRCC’s Cecil Murray Center for Community Engagement. “…she found in the program a kind of theologically grounded activism that honored the social justice legacy of the black church.”

The model for the PTM curriculum in 2006 was the Harvard Divinity School’s nearly decade-old Summer Leadership Institute, which provided executive training for clergy and lay leaders involved in community development. Two years later, administrators at the divinity school suspended their program, but the PTM team had already begun to adapt the Harvard curriculum.

“Their model focused on more economic development—job creation, constructing buildings, developing programs—that you can measure immediately versus civic engagement, which would take longer,” Whitlock says. “It was you come to class. You complete your class. You receive your certificate, and it’s over. In the second year we revised the PTM program to include a primary focus on civic engagement and policy analysis.”

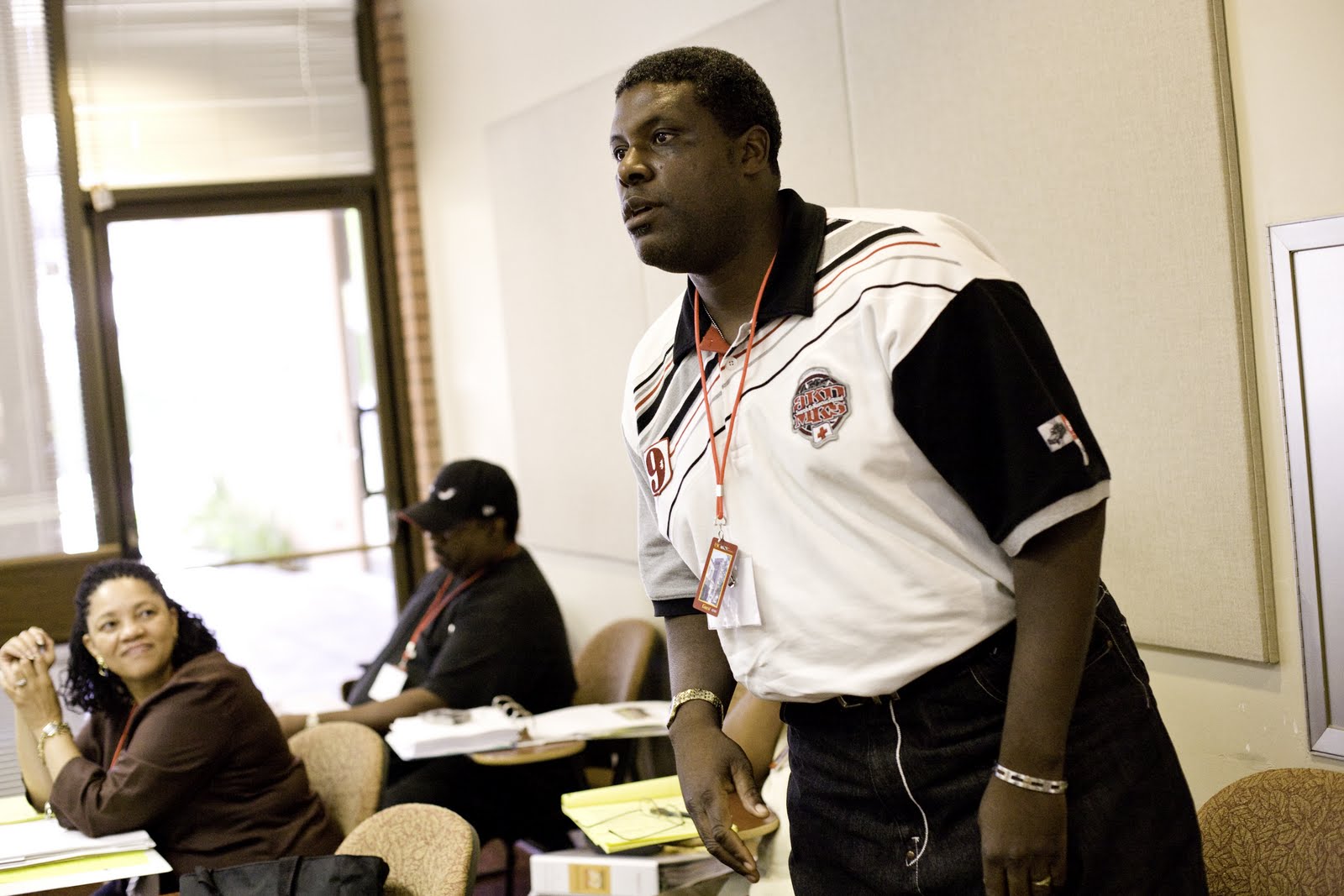

In practical terms, this meant shifting from a classroom-oriented strategy that entailed two classes a month for four months—as well as a financial incentive to keep participants engaged in a protracted, non-residential program—to a practicum-focused curriculum that included residential components, hands-on mentoring and an integrated approach to policy initiatives and community development. A modest tuition fee also encouraged participants to have a stronger sense of investment in their training.

“We take them right from the classroom into existing civic engagement work that’s going on,” says Rev. Eugene Williams, PTM’s co-founder who also heads the faith-based Regional Congregations and Neighborhood Organizations Training Center. “By year three, that became the standard we were using.” The four phases of the current iteration of the PTM program are designed to equip leaders with the skills they need to manage partnerships in the public arena and to encourage the cultivation of networks that can help sustain socially engaged activism in the black church and beyond. They are also geared to change theological mindsets that keep leaders from moving beyond the walls of their congregations and into the public square.

Download a PDF of the report

Nick Street was a senior writer with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.