What exactly is the shelf life of a headlining rock band and an equally headline-grabbing pastor? When I heard that U2 had summoned megachurch pastor Rick Warren to minister to them in their grieving over the death of their long time road manager Dennis Sheehan, I thought, “This is the end.”

Now don’t get me wrong, I like U2, or at least I once did. When they forced their latest album on everyone with an iTunes account, the fiercely independent band became just another shill for corporate interests.

And in Rick Warren, they summoned another corporate leader to help them in their time of need. After all, what are megachurches if not large religious corporations intent on expanding their brand in the religious marketplace? Rick Warren’s own Saddleback Church has franchise sites across 10 cities in Southern California and another four in Berlin, Hong Kong, Manila and Buenos Aires. Just like Apple, McDonald’s or U2, you get exactly what you expect when you visit, with content quality controlled from headquarters in Orange County, California.

The U2-Rick Warren relationship is hardly anything new in American Christianity. Pastors and evangelists have long courted relationships with leading musicians, actors and other culture producers as a way to extend their religious brand in secular culture, while the celebrities burnish their brand among the faithful.

In many ways, this model is still popular among a large segment of Christianity that crosses generational and ethnic lines—although not necessarily in the same congregation. One only need visit Saddleback to see the older version, or Hillsong, an Australian megachurch with outposts in 14 cities around the world, to see a newer version. At least in its New York and L.A. incarnation, Hillsong is a younger and more ethnically diverse version of churches like Saddleback. It includes U2-worthy worship performances that draw thousands of young adults each weekend.

Hillsong Worship Service in Australia (Michael Chan/Flickr)

Hillsong Worship Service in Australia (Michael Chan/Flickr)

And, Hillsong has its own celebrity component, most notably with former bad-boy pop-artist Justin Bieber counted among its members. His participation in the church’s annual conference, of course, has been publicly noted by the church, and gossip blogs have been abuzz with his friendship with its pastors.

Yet between the increasing number of people declaring they have “no religion in particular,” and the many emerging congregations that are intentionally small and community oriented, I wonder about the future of these large churches that focus on producing pop-culture oriented spiritual experience through their music and their connections to celebrities.

I recently attended a small conference celebrating 13 years of Laundry Love, an outreach/service program that has its origins in a small church in Ventura, California. The premise of Laundry Love is to provide free-of-charge laundry services for the homeless and working poor, both as a way to help them with this essential task, and to develop relationships with people they meet. What I heard at the conference was less “we’re here to help you” than “we aim to show love for love’s sake.” There was no agenda other than building a community of mutual caring.

Watch a video about Laundry Love:

Laundry Love demonstrates an emerging sensibility on the part of spiritual and religious people, as well as those who claim no allegiance to either, to “do something” for others simply as a way to give back and to develop a sense of community, with no strings or expectations attached. These efforts can be found in a number of places—within churches, mosques, temples and just among friends who organize themselves to “give back.” For many, this is “church,” not the buildings, music or formal programming, and definitely not the celebrities.

Most people who are involved in a megachurch will tell you that the real action isn’t in the worship performance, but in the small groups where community and relationships are built. Nonetheless, in many ways, it seems as though these emerging forms of embodied and inclusive spiritual communities are attracting an increasing number of participants who are dissatisfied with the large, church-as-performance model. But are these different models of church really competing for members, or is something else going on that allows each to not only exist, but to thrive?

Based on several observations we’ve made in our research on creativity and innovation, it is clear that the mega/performance churches have a core of attenders, as do the smaller groups. But our working hypothesis is that some set of church attenders are seeking their spiritual nourishment and community simultaneously from multiple congregations. We’ll be testing this hypothesis as we go out and interview people at such churches this summer.

Just as music lovers might attend a U2 concert and a small coffee house set in the span of a few days, it seems possible that at least some people who attend Saddleback or Hillsong are also attending and participating in smaller faith communities for complementary reasons. In other words, some people may need more than one church or experience in order to find what they’re looking for.

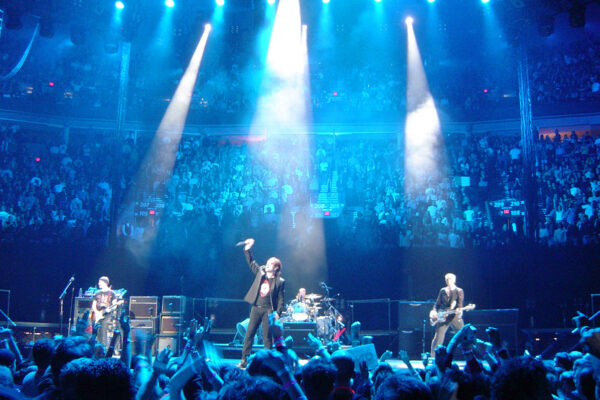

Photo Credit: Matt McGee/Flickr

Richard Flory is the executive director of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.