It is reasonably easy to be an armchair critic of religion. There are ample examples of religious leaders who compromise the values of their tradition, and the fundamentalists of every religion are inevitably out of step with the latest findings of modern science. Furthermore, it is morally abhorrent when power-hungry political leaders justify violent acts in the name of their religion.

But the storyline about religion gets more complicated when one examines religious people in the trenches, serving the poor and disenfranchised of their societies. During the last six months I have traveled in five different African countries with Sister Jane Wakahiu, executive director of the African Sisters Education Collaborative. When you see what nuns are doing on the ground, it is quite amazing. And I say this as a non-Catholic.

Sisters are heading some of the best primary and secondary schools throughout Africa. They are also administering health clinics and hospitals in many of the poorest areas of society. And they are intervening in the lives of children with disabilities, affirming their rights as human beings.

For example, in Nairobi, Kenya, I met with several sisters who were working with over 3,000 children in the city’s slums. With the assistance of World Vision, they had trained 50 health advocates from the local community who were teaching parents basic hygiene and other skills—tackling health problems at their root, rather than simply providing secondary care. They had a first-class primary school that was overflowing with children. And they had gotten into the farming business in a major way, hiring local people to grow vegetables of every description. They also had a fish farm where they were raising tilapia. And they had chickens, pigs, cows, geese and other animals—tended by people that they hired from the nearby slum.

Two weeks ago I was in Zambia and traveled by four-wheel drive vehicle outside of Lusaka to an isolated area where three Missionary Sisters of the Holy Rosary had put down roots. The sisters had developed a skills center where they offered training in tailoring, cooking and catering. They had a dozen or more healthy cows and had established a dairy collaborative with a number of local farmers. They also had a bakery that was producing trays of bread that were sold to the local community. In addition, they were raising maze and vegetables, and had a number of beehives. Perhaps most intriguing to me was that they had engineered a series of concrete-lined ditches that were draining swamp water from their property into a lake. The profits from these various enterprises supported the sisters and also enabled them to hire a number of local residents. The sign at the entrance to their property included their mission statement: “Community empowerment through community development, education and health.”

Catholic sisters, of course, are not unique in their social commitment. On several occasions I have walked with Mama Maggie, founder of Stephen’s Children, through the slums of Cairo, where she has created an incredible network of nursery schools for the children of parents who make their living sorting garbage. I have also spent many hours with Jean Gakwandi, a survivor of the genocide in Rwanda, who has established a holistic approach to dealing with the post-traumatic stress of hundreds of widows and orphans. Along with Catholic sisters, these are people who find their strength in daily practices of prayer and meditation.

Religiously inspired social service comes in many different forms. In many cases, it simply applies a Band-Aid to the problem by offering a meal or a bed to someone. This has its value, but it doesn’t have any long-term effect on the source of the problem. I am more impressed with religious people and organizations that establish institutions, such as schools, hospitals and programs that address root causes of poverty. And I have respect for coalitions of religious leaders that attack political corruption, which I have witnessed in countries such as Uganda and Kenya.

Religion is an incredibly important institution within civil society. We should not dismiss it because of its fundamentalist strains; nor should we throw the baby out with the bathwater, simply because of a few corrupt religious leaders. Religious critics have a role—I am one of them—but let’s also look pragmatically at what religious people are doing in society and judge them by the fruits of their labors.

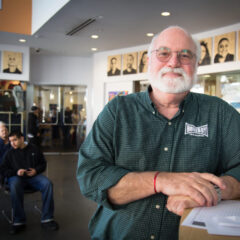

Donald E. Miller is the co-founder of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.