Most of my memories of Jewish worship services are an amalgamation of the hundreds of services I’ve attended throughout my life. But there are a few that stand out. At a Shabbat service years ago, the leader, Amichai Lau-Lavie—who was then a performance artist and Jewish educator—said something like: “Trying to pray using a prayer book is like attempting to have sex while holding the Kamasutra.”

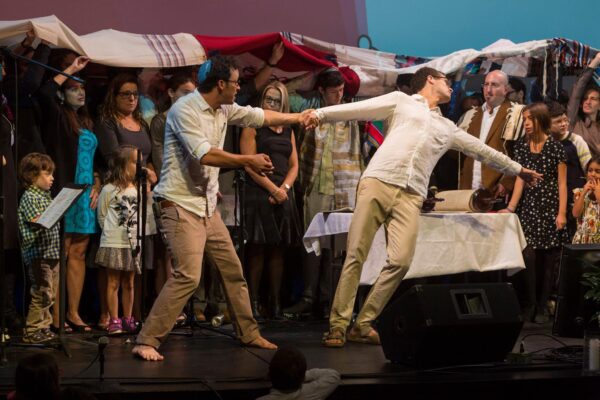

As is the case across traditions, Jewish organizations are concerned about the decline of religious affiliation and are looking for new ways to keep people interested in religion. Amichai has developed a thriving career of making Jewish texts and stories accessible with his ability to use dramatic flair to engage people in religious ritual. In 1999, he founded “Storahtelling,” a theater troupe (and later an education and training institute) that developed a method to revitalize the experience of reading the Torah—a central aspect of the Jewish worship service. Instead of how it’s usually done—a single person stands before a congregation looking down and chanting what they’re reading (in Hebrew) from an unscrolled Torah—a Storahtelling troupe imparts biblical stories in English and Hebrew, using drama, music and humor while breaking the fourth wall to share reflective observations as well as snarky comments.

This year for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, I traveled to New York City to attend Lab/Shul, the latest innovative offering from Amichai, who recently was ordained as a rabbi, and his talented team of artists, musicians and educators. Lab/Shul is an “everybody-friendly, artist-driven and God-optional experimental community for sacred Jewish gathering.” This year (2016/5777) marked Lab/Shul’s fourth Rosh Hashanah “worship event,” as it is conspicuously called, rather than “service,” which is more typically used.

Attentiveness to language and aesthetics is a key aspect of Lab/Shul’s innovative approach. Much like receiving a playbill when entering a theater, each attendee was handed an informational booklet as they entered the venue. The cover illustrated the theme of this year’s High Holidays, re:love, with a Keith Haring-esque graphic figure holding a heart. In his welcome note, Amichai described his motivation for this branding decision: “… [I]n the face of toxic politics, communication breakdowns, and digital distractions, we’re returning to the basics: what, who and how we love.” He grounded this universalistic pursuit in Jewish particularism, explaining: “‘Love’ as a verb, is a central Jewish value, echoing throughout generations as both commandment and plea.” Also included were selections from All About Love: New Visions by feminist social activist, bell hooks.

Attentiveness to language and aesthetics is a key aspect of Lab/Shul’s innovative approach. Much like receiving a playbill when entering a theater, each attendee was handed an informational booklet as they entered the venue. The cover illustrated the theme of this year’s High Holidays, re:love, with a Keith Haring-esque graphic figure holding a heart. In his welcome note, Amichai described his motivation for this branding decision: “… [I]n the face of toxic politics, communication breakdowns, and digital distractions, we’re returning to the basics: what, who and how we love.” He grounded this universalistic pursuit in Jewish particularism, explaining: “‘Love’ as a verb, is a central Jewish value, echoing throughout generations as both commandment and plea.” Also included were selections from All About Love: New Visions by feminist social activist, bell hooks.

The High Holiday branding was consistent throughout the event: The logo was also featured at the bottom of each slide projected onto a huge screen, in lieu of a prayer book. Each prayer was included in Hebrew, transliteration and English translation. (While relatively common in churches, projection screens are less frequently used in synagogues, where attitudes about the acceptability of incorporating technology vary considerably.)

While reading a translation of a prayer that I found incredibly poignant and moving, I thought: “I should read the English more often.” I stopped reading the English translations years ago, because at best, the words didn’t speak to me and at worst they included sentiments I found offensive. A moment later, Amichai stopped to call attention to how the Hebrew speakers among us likely noticed that the English translations are far from direct.

The “Sources and Inspiration” section of the booklet elaborates, acknowledging that for many, “[T]he traditional words of worship often present a barrier to finding meaning and connection.” In an effort to “attempt to make prayer accessible, relatable and honest to our personal experiences,” they’ve made a number of liturgical modifications. One major change, they explain, is in their use of God language: “We’ve replaced the baggage-laden word ‘God’ with a multiplicity of other names and prisms that reflect the diversity of historical and personal interpretations of what is ultimately beyond language.” These changes and the many others that Lab/Shul is incorporating into its events are the result of purposeful reflection about how to effectively merge the method (how we pray) with the meaning (why we pray).

There are communities around the country that are heeding the same impulse by using a variety of innovative approaches. Lab/Shul is one of seven Jewish communities that make up the Jewish Emergent Network.* The leaders of these communities “share…a devotion to revitalizing the field of Jewish engagement, a commitment to approaches both traditionally rooted and creative, and a demonstrated success in attracting unaffiliated and disengaged Jews to a rich and meaningful Jewish practice.” Each community’s approach to coupling meaning and method is unique. Some are comfortable with more traditional God-language, see prayer books as a valuable tool and take a less theatrical approach than Lab/Shul. Others emphasize social justice or practices embedded in Jewish culture.

These communities appeal to people, like me, who are not interested in conventional religious practice and affiliation, but are not “nones” (the growing share of individuals who are unaffiliated with any organized religion). By adapting and transforming Jewish ritual and tradition, these groups appeal to the scores of people who want something in between: those of us who are looking for “some.”

*With her colleague Ari Y. Kelman, Belzer will be working for the next four years to support the Jewish Emergent Network Fellowship by facilitating organizational learning through evaluation. The Fellowship, the first major collaborative effort of the Network, aims to train the next generation of rabbis to “take on the challenges and realities of 21st century Jewish life in America in a variety of settings.”

Photo Credit: Kate Glicksberg (http://www.interstatial.com/)

Tobin Belzer is a contributing fellow with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.