To the chagrin of many Muslims, Ayaan Hirsi Ali is back on the talk show circuit, promoting her new book, Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now.

And, for the first time, as I watched Hirsi Ali subdivide the Muslim world into three groups—rather than paint Islam and Muslims in broad brush strokes—I began to wonder whether she was finally changing her tone. For years, Hirsi Ali has labeled Islam as a religion of violence and intolerance, pointing to her personal story as proof.

So, I picked up her book, hopeful that if Hirsi Ali believes a reformation is possible, then maybe she also has a new starting point. I did find a more nuanced argument by the author. Hirsi Ali’s fundamental problem is not that she’s asking for a reformation. Many Muslims, too, are troubled by the rise of fanaticism; they want to halt the rise of ISIS and to limit the appeal of such groups to Muslim youth. But Hirsi Ali’s language and preconditions will stall a debate about reformation from the get-go.

Hirsi Ali begins her book by dividing Muslims into three categories. She describes the “Medina Muslims” as intolerant and prone to violence—those more universally described as Salafis. The “Meccan Muslims” are the majority of peace-loving Muslims who she says are mostly at odds with modernity. She defines “dissident Muslims” as both unbelievers and believers who believe that Muslims and/or Islam must change.

Hirsi Ali then says that for a reformation to happen, Muslims must strip the prophet of his “infallible” nature and declare the Qur’an a man-made document. Muslims must re-prioritize this life over the afterlife in order to remove the appeal of martyrdom. They must embrace secular laws over “anachronistic” shariah laws and rid themselves of “religious police” or “politically empowered clerics.” Finally, Muslims must reject the use of the sword and become a true religion of peace.

Her argument has evolved. And she even makes points that I believe many Muslims would agree with. For example, on various talk shows, she has said that theological reform must come from within the religion itself (something that seems to run counter to her argument in her book) and that the West must align themselves with the reformers and those that respect democratic change, rather than despotic regimes like Saudi Arabia, which exports a harmful version of Islam.

But her requirements ask Muslims to denounce a religion they love, and in essence, declare themselves atheists. “Islam is not a religion of peace,” Hirsi Ali declares. Such derisive language makes it difficult to take her seriously as a reformer who wants peace. Instead, it only attracts other “warriors”—those who both hate Islam and those who want to fight in the name of Islam—while alienating the “reformers” out there who have been working towards change within their own communities for decades.

If she really wanted to “reform” Islam to be a “peaceful” religion, she might start by looking to others who are challenging the status quo. But the “reformers” include people who believe that shariah can be a part of our modern world, if interpreted correctly. They are people who believe that Islam can flourish under secular governments, that Islam can be a source of justice and peace simultaneously.

I grew up with hearing the words of one such person. Dr. Maher Hathout believed in Islam, he lived Islam, and he also believed in modern principles of democracy, tolerance and love. He constantly repeated phrases like, “there is no compulsion in Islam.” Even though he found Salman Rushdie’s book The Satanic Versus insulting, he condemned the fatwa against him and defended his right to free speech. (He faced death threats from Muslims because of his stance.)

Hathout called on Muslims to interpret the Qur’an for themselves—to study, to use reason and to question those in robes. There is no Islam without thinking, he said.

He became an integral part of LA’s interfaith community, joining forces with Jewish and Christian leaders to speak out against injustice and promote interfaith dialogue. He condemned violence perpetrated by Muslims and non-Muslims. And he helped mentor new generations of Muslims who see no conflict between Islam and modernity.

But he did not ask to be called a dissident or a reformer. He just was one.

He passed away earlier this year and the community felt his loss deeply. But, he left behind a legion of reformers—all around Los Angeles, the U.S. and abroad. The question is how can we make these reformers’ voices heard.

Hirsi Ali’s book fails to recognize that the calls for reform have been going on for decades—arguably even for centuries—within the tradition itself. Reformers are tackling many subjects: What is shariah? Where is its place in the modern world? What is jihad? How does one eliminate extremism in the name of Islam and how does one make such ideologies less popular to youth? It is these debates that must be heard and discussed—by both Muslims and non-Muslims.

Here are just a few interesting people—scholars and activists—who I believe should be leading the way. They are believers who begin their critiques from a place of love and compassion, along the same lines that they understand their religion.

- Khaled Abou El Fadl, professor of law at UCLA, has written a book calledReasoning with God: Reclaiming Shari’ah in the Modern Age.

- Intisar Rabb, a professor of law at Harvard, has written a book called, Doubt in Islamic Law: A History of Legal Maxims, Interpretation, and Islamic Criminal Law.

- Omid Safi is a professor, blogger and director of Duke’s Islamic Studies Center who has written a books about the prophet called, Memories of Muhammad and another book titled Progressive Muslims.

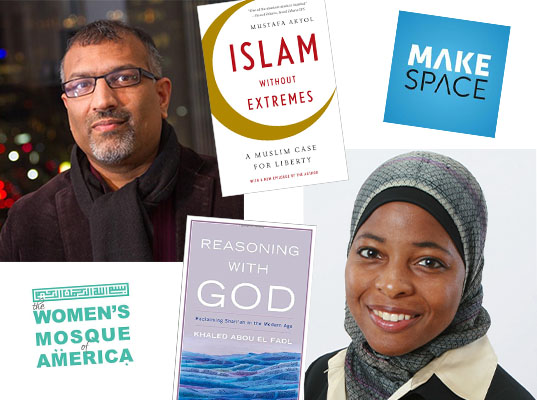

- The Women’s Mosque of America (in Los Angeles) is a group of Muslim women who recently started their own mosque as a way to “uplift the Muslim community by empowering women and girls through more direct access to Islamic scholarship and leadership opportunities… The Women’s Mosque of America plans to provide programming, events, and classes open to both men and women that will aim to increase community access to female Muslim scholars and female perspectives on Islamic knowledge and spirituality.”

- Karima Bennoune, author of Your Fatwa Does Not Apply Here: Untold Stories from the Fight Against Muslim Fundamentalism, travels around the world interviewing a wide range of Muslims who have stood up against the Muslim fundamentalists.

- Mustafa Akyol is a Turkish thinker who writes about the roots of progressive Muslim thought in his book Islam Without Extremes .

- Khaled Latif is a NYU chaplain who has worked closely with law enforcement for years and helped to build an engaged and progressive community of Muslim youth.

- Suhaib Webb is an imam who recently left Boston to join an interesting new group in the Virginia/ D.C. area called Make Space, which hopes to create a safe space of worship for all Muslims.

- Shahed Amanullah, co-founder of Affinis Labs, an incubator that helps set up companies that will draw its talent from Muslim communities as a way to counteract the influence and allure or extremist groups like ISIS.

These are just a few of the reformers out there. Manal Omar, arguably another “reformer” and the acting vice president for the Middle East and Africa Center at the United States Institute of Peace, argues the fight against extremism must come from local voices, whose respective communities help to temper the lure of extremism. We must tap into those voices as we debate how to make this scholarship and messages resonate with youth. How does one affect the group that Hirsi Ali calls the “Medina Muslims”?

The work of these reformers is exciting and intriguing. And I believe they would be willing to debate anybody, whether religious or secular or an atheist, who upholds an environment of tolerance.

This commentary was re-posted by Salon.

Rhonda Roumani is a contributing fellow with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture and a journalist fellow with the Spiritual Exemplars Project.