This piece originally appeared in Boom California.

A hallucinogenic brew called ayahuasca is having a heyday in the United States. Rolling Stone, Fusion, VICE and other trend-spotting news outlets have posted stories about spiritual adventurers tripping on the stuff during private rituals in hipster outposts like Brooklyn and Berkeley as well as remote jungle settings in Central and South America.

The thick, earthy tea is concocted from a complementary pair of plants that grow in the rain forests of the Western Hemisphere. Depending on whom you ask, ayahuasca—called “the mother” by devotees—opens the doors of perception, provides a window onto the soul, lures naïve Westerners into the heart of darkness or crams a decade of psychotherapy into a few hours.

The legal status of ayahuasca is ambiguous in the United States, though it has been used in shamanic rituals for centuries.

Why is this ayahuasca’s moment? A recent piece in The New Yorker framed the popularity of ayahuasca as yet another wellness fetish in the current “Age of Kale.” That breezily dismissive conclusion doesn’t account for the uptick in ritual use of the brew among people who aren’t chasing the latest Burning Man-inspired fad. For example, in a segment of its special digital series on mental health care, CBS News examined the buzz—and controversy—around Veterans for Entheogenic Therapy (VET). VET organizes retreats where ayahuasca is used to treat service members suffering from depression, addiction and post-traumatic stress disorder.

That focus on physical and emotional experience, particularly the experience of trauma and the search for healing, highlights an important but underreported trend: Though millions of Americans, particularly young adults in big coastal cities, are dropping out of organized religion, many of those dropouts are still looking for experiences of self-transcendence. That can mean volunteering at a homeless shelter, learning meditation or simply cultivating a sense of “something bigger than myself.” For some religious “nones”—those who check “none of the above” on religious identification surveys—self-transcendence also entails the ritual use of ayahuasca. And nowhere are these broad developments more apparent than California, which for decades has served as an engine for both counterculture and religious disaffiliation in the United States.

A “none” whom I’ll call Brianna unexpectedly introduced me to one of California’s ayahuasca subcultures during an interview about Brianna’s involvement with a secularized form of Buddhist meditation.

Brianna and I agreed to meet on a shady patio outside a coffee shop at the Farmers Market on Fairfax—it was midafternoon on a warm weekday in Los Angeles. Brianna, a financial consultant, had told me she would be coming from a workout, and that I should look for a woman in her late 20s with long, auburn hair wearing a gray tank-top and running tights.

I was instantly envious of Brianna’s arms. She had the guns of someone who manages a handstand with aplomb, who can lob a medicine ball into next Tuesday.

Not surprisingly, self-discipline and a no-nonsense approach to life quickly emerged as two of Brianna’s strongest character traits.

“I started out very skeptical,” Brianna said of her initial experience with a university-based research center that has become a leader in teaching meditation practices that have been stripped of their religious trappings. “It’s kind of like, you know, this is for hippies, and I’m not a hippie.”

Brianna said that as she deepened her level of participation in the mindfulness program and cultivated her own regular meditation practice, she noticed changes in herself that she liked.

“It’s definitely an effective tool,” she said. “Being able to distance yourself in a healthy way from emotions or experiences, you don’t have to rationalize everything. You just experience it and move on.”

Brianna, a Southern California native, grew up nominally Catholic and still believes in what she calls “a higher power.” But rather than identifying that power as the God of traditional Christianity, she said she equates it with the sense of awe she feels when she is in nature or when she contemplates the infinite vastness of the night sky.

As we began to wrap things up, I asked Brianna whether there was anything important about her story that we’d not covered. “Yes,” she replied. Then she told me that over the past year and a half, she had participated in three ayahuasca rituals.

“I was super skeptical about that too,” she said. “But now I’m a believer.”

Unlike members of the 1960s counterculture who used psychedelics to “tune in and drop out,” many of today’s religious “nones” are both squarely in the mainstream of American professional life and willing to experiment with spiritual technologies that are more typically associated with the cultural fringe. Erik Davis, a scholar of contemporary American esoteric spirituality and author of Visionary State: A Journey Through California’s Spiritual Landscapes, has observed this paradoxical trend first-hand: “In my work,” Davis said, “I’ve encountered people from a science background or secular background who are concerned about losing their reason, but who are also happy to see that there’s a way to engage the weird stuff,” like psychedelics.

Davis added that the willingness of more-or-less secular seekers like Brianna to scratch their spiritual itches by using ayahuasca “blows my mind.”

“Even in the psychedelic world,” Davis said, “ayahuasca is fucking hardcore. Its visionary dimension is robust and bizarre. But psychedelics are very plastic, and your intention helps to shape the experience.”

In keeping with her pragmatic approach to both mindfulness and shamanic medicine, Brianna said that while all three ayahuasca rituals were useful for her, her most recent experience was life altering: “It was one of the best experiences in my entire life. Perhaps the best.”

She described lying on a meditation mat in a state between consciousness and unconsciousness while the shaman chanted, drummed and made his way around the room to administer healings to Brianna and the other participants. During the last ritual she attended, she said experienced “pure joy” for several hours.

I asked Brianna whether she thought ayahuasca was compatible with the discipline and insights she’s developed through her meditation.

“They’re definitely complementary,” she said. “The idea is that ayahuasca, the plant, she gives you what you need at the time. She can be harsh sometimes or she can be very loving. I’ve only had good experiences so far.”

On a Wednesday night a few weeks later, I sat on a small pallet of bedding that I’d made for myself and swayed gently as the shaman’s chanting shifted into a languid, sweetly melancholy register.

The room was dimly lit—the only sources of illumination were a small candle and cool, silver-white streetlight seeping through sheets of creamy parchment that our host had used to cover the big windows in the living room of his house on L.A.’s Westside. There were eight other participants, along with the shaman and his attendant. The shaman—about six feet tall with short, shaggily cropped dark hair—was a Frenchman who had traveled to the Peruvian Amazon to find a cure for his heroin addiction. He spent the next ten years in the jungle as an apprentice to an indigenous medicine man.

His attendant was a fifty-something psychotherapist whose pale shawl and shoulder-length gray-blonde hair gave her a ghostly appearance as she moved around the room to check on us and administer healings.

Our little nests of blankets and pillows outlined the perimeter of the space, creating a semicircle in front of the darkly patterned rugs and tapestries that demarked the shaman’s altar. Close at hand, the shaman had a large green bottle of ayahuasca, a small octagonal drum, a wooden whistle and a feather-duster-sized bundle of papery leaves that evoked the sound of birds flapping through a forest when he shook it.

Smoke from mapacho, the Amazonian tobacco that often grows near the ayahuasca vine, hung in the air.

At the start of the ritual, the shaman told us that his singing—a combination of North and South American indigenous languages as well as a shamanic version of speaking in tongues—was meant to shape the flow of energy in the room rather than convey any sort of meaning. While he was explaining this, I was clinging to a small plastic bucket. Ayahuasca often causes intense vomiting, and in a few minutes I was retching with such gusto that, at one point, the shaman stopped chanting and said, “Nick, you need to get control of your mind.”

After the purging came the visions. In the kind of half-conscious state that Brianna had described in recounting her experience, I became vividly aware of the toxic mixture of shame and self-loathing that I’d marinated in as a closeted gay kid growing up in Alabama during the 1970s and ’80s. At one point I even glimpsed myself as a fetus, absorbing metaphysical poison through the umbilicus while I was still in my mother’s womb.

“Fuck that,” I said, banishing dark, smoky tentacles of shame that were trying to wrap themselves around me.

Dramatic insights like that are common during long meditation retreats. I’ve been a Zen practitioner for fifteen years, ordained as a priest in 2007 and soon thereafter moved into a small Buddhist temple.

Zazen (Zen meditation) and the shamanic use of ayahuasca are both spiritual technologies designed to help seekers cultivate a state of awareness freed from the distortions of reality caused by tightly held beliefs, concepts, and other habits of mind.

Carefully managed rituals traditionally surround both practices. These lattices of sound, spectacle, and movement act as a psychological container for the powerful emotional energies—awe, wonder, fear and anger, for example—that are often uncorked in the process.

A couple of times over the course of the ayahuasca ritual, the visions and physical sensations I was experiencing became almost too much to bear—for example, at one point I watched my body become transparent. At another, I felt myself melting into a liquid form. Seeing the sweater at the foot of my bed writhe like an earthworm was also disconcerting. Some prior instructions from my Zen teacher (“no matter what happens, just relax and float downstream”) helped me navigate most of those intense experiences and waves of feeling.

Toward the end of the ritual, a bout of paranoia sent me crawling (I couldn’t walk) out of the circle and onto a poolside patio. After several veteran ayahuasca-nauts failed to coax me back inside—their voices seemed out of sync with their mouths when they spoke, which didn’t help my anxiety—the shaman himself intervened: “You’re safe here,” he said as he held me by the shoulders, “and everyone here loves you.”

That did the trick. I was embarrassed by the group’s exuberance when I finally rejoined the circle. The room was suffused with golden light, and I wept in response to the intense love that I felt as the ritual reached a crescendo and began to wind down.“You have to remember that you’re always looking into your own mind,” my Zen teacher told me when I recounted my experiences to him the next day. “It’s your fear or your joy. And fear and joy are just more thinking. Don’t grab onto them and just go back to your practice—that’s staying in the circle!”

These insights into psyche and the numinous are by no means unique to Zen or the ritual use of ayahuasca. In my work as a journalist covering religion, I’ve interviewed many people who have had similar experiences during Pentecostal prayer, yogic breathing, and other spiritual practices.

Some of these paths intersect or even overlap. For example, there’s a connection between the kind of spiritual yearning that often attracts people to Zen as well as ayahuasca—specifically, the desire to see reality as it is, not filtered or refracted through the lenses of belief and cultural conditioning.

That’s why ayahuasca is the spiritual doorway of choice for many seekers in the age of religious “nones.” While some young adults are leaving organized religion to pursue decidedly unspiritual materialistic goals, many other “nones” are looking for firsthand experiences of absolute reality, which they feel the doctrines of traditional religion have obscured.

In the case of Brianna and other religious “nones,” the intention that guides their spiritual seeking is to connect with the sublime or divine in a purely experiential way that casts aside rigid ethical formulas and speculative theologies.

“I know that there’s some higher power,” Brianna said. “But do I think we have to follow any specific rules, and is there an afterlife? Like, no.”

Brianna added that the goal of life is the happiness that comes from being a good person—someone who works to create productive lives for herself and others. That hopeful formulation impressed me as good medicine for heartsick times.

“I suspect this kind of seeking is happening everywhere,” Erik Davis said, “even if California is the most obvious example. Through technology and media, we’re all kind of California now.”

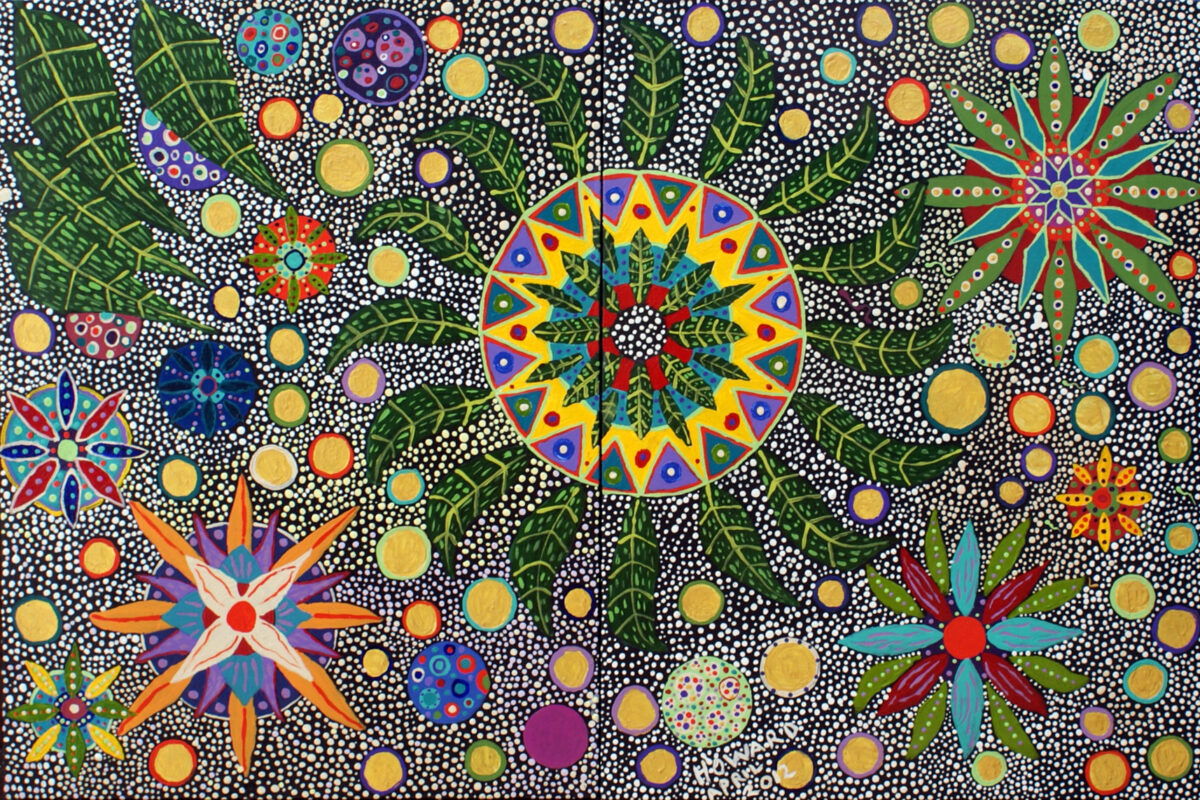

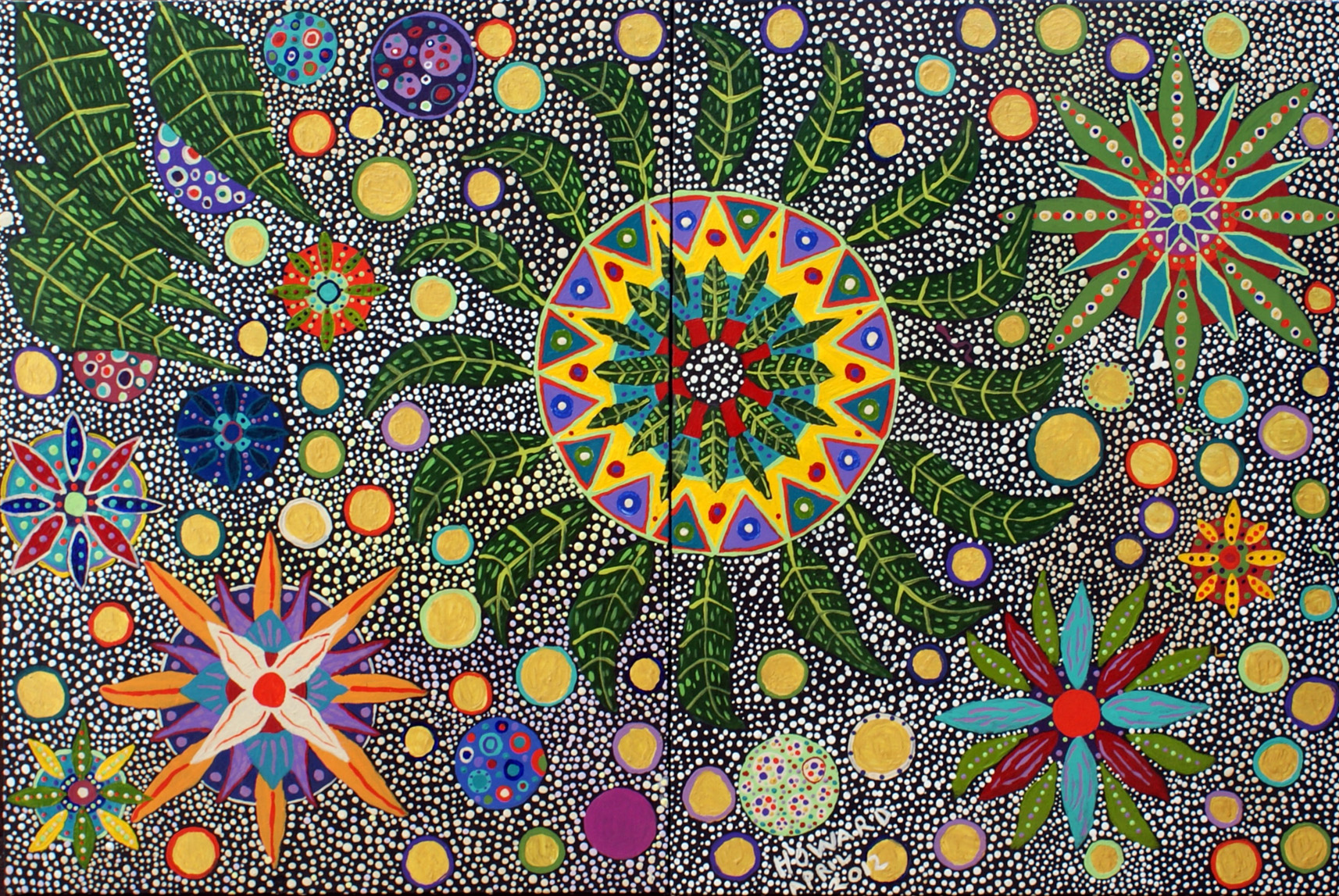

Image Credit: Howard G. Charing / Flickr

Nick Street was a senior writer with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.