Many observers on both the right and the left see the 2012 national and state elections as the death knell of evangelical political power. Albert Mohler, president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, called the election “an evangelical disaster” and a “moral catastrophe.” He concluded his post-election analysis with despondent self-reflection:

Clearly, we face a new moral landscape in America, and huge challenge to those of us who care passionately about these issues. We face a worldview challenge that is far greater than any political challenge, as we must learn how to winsomely convince Americans to share our moral convictions about marriage, sex, the sanctity of life, and a range of moral issues. This will not be easy.

On the other side, Jack Jenkins, writing for the thinkprogress.org, calls the elections a “resounding defeat for the political engine that has long catapulted the GOP to power: The Religious Right.” It was nothing less than an “implosion” of the Religious Right, he writes.

In the middle are those like the moderate Southern Baptist writer, Jonathan Merritt. Writing for The Atlantic’s politics blog, he declares the 2012 elections to “mark the end of evangelical dominance in politics.”

All of this, to me, seems like diagnosing heart disease after a heart attack. If we want to see when the symptoms first arose, we could do worse than follow Rick Warren, pastor of Orange County’s Saddleback Valley Community Church, one of America’s largest churches and the focus of my new book, Sacred Subdivisions: The Postsuburban Transformation of American Evangelicalism.

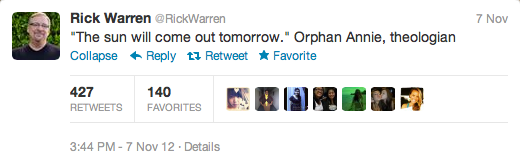

Last week, on the day after the presidential election, he made no broad statements on the impact of the election, nor sent any politically tinged emails to his followers. He instead sent out a grand total of one tweet regarding the election:

And that’s it. Since then he’s tweeted advice to young pastors, Bible verses, pithy motivational statements, and daily observations, like how his “Muslim neighbor neighbor gave #PurposeDrivenLife to his Jewish friend.” But not another word on the supposed “end of evangelical dominance in politics.”

This mostly likely has to do with the fact that Warren, as usual, is far ahead of the curve on this cultural-political shift. Back in 2004, Warren sent out an email to hundreds of thousands of followers right before the presidential election imploring them to vote according to their evangelical values. He told them:

For those of us who accept the Bible as God’s Word and know that God has a unique, sovereign purpose for every life, I believe there are five issues that are non-negotiable… In order to live a purpose-driven life—to affirm what God has clearly stated about his purpose for every person he creates—we must take a stand by finding out what the candidates believe about these five issues, and then vote accordingly.

These five issues were abortion, stem-cell research, gay marriage, human cloning, and euthanasia. There was no hint of the Orphan Annie insouciance of 2012. He ended his 2004 campaign email in no uncertain terms:

Please, please do not forfeit your responsibility on these crucial issues! This election REALLY counts more than most others have. Be sure to vote, and be sure to encourage every Christian you know to vote on Tuesday. If you are able to vote early, do so. Then ask all your Christian friends on Tuesday “Have you voted yet?” and pray for godly leaders to be elected.

What happened to this Rick Warren? I believe it is the same thing that is happening in large, dynamic, and growing evangelical churches across America. There is a growing realization that these cultural outposts along the Maginot Line of conservative Christian America are crumbling and their passionate defenders are fewer each election season. What continues to fill evangelical pews are the issues that Warren has long focused on: self-fulfillment, personal growth, small-group bonding, and active community work.

It’s fascinating that Warren realized the Religious Right’s causes as losing and irrelevant at a moment when the whole movement seemed ascendant, right after the 2004 electoral college landslide for George W. Bush. Only a few weeks after the election, Warren was on the Larry King Show when he was asked if he was concerned about how “politically motivated” the “evangelical right” was during the recent election. “Yeah,” Warren responded. “There’s a lot of things that are said in the name of Christianity, not just in the past but right now, that I’d like to totally disavow.” He went on to say that members of all faiths can come together over things they have in common, namely working to make society “less vulgarized.” Not a mention was made of those “non-negotiable issues” he had so vigorously promoted.

By 2005, he had become the most famous pastor in America, and best known for his supposedly moderate, inclusive brand of evangelicalism. Despite some cracks in this new display—most notably his 2008 election email in which he implored his local church members to vote to ban gay marriage in California, on which he later hedged, equivocated, and eventually abandoned—Warren has remained focused on those things that draw individuals to his church and keep them coming. And they happen not to be any of the things associated with the Religious Right.

Photo Credit: Mark Hogan/Flickr

Justin Wilford is a guest contributor with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.