This post originally appeared on Religion Dispatches.

Early this morning, when Donald Trump accepted the presidency of the United States, Ronald Reagan and Jerry Falwell were somewhere enjoying the last laugh. Their vision for the nation had held firm for almost four decades, culminating with a candidate who spoke their truths more clearly than either could have imagined. As leaders of America’s turn right, the two had convinced millions of Americans that a godly America was a good America, and that God wanted a strong nation of self-reliant, successful conservatives who if not Christian, likewise supported free markets and traditional families.

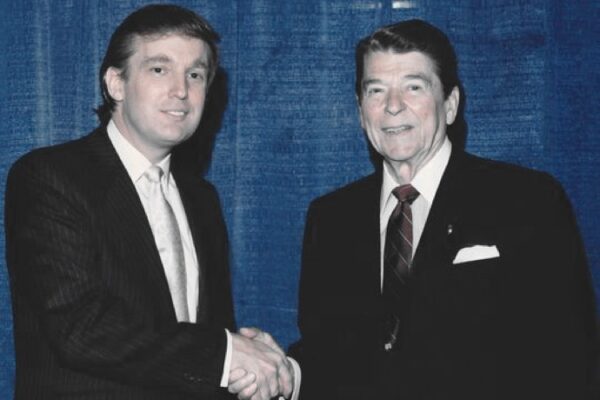

Trump, who espoused similar ideas in saltier language, is their heir.

The Reagan/Falwell message was tailor-made for white evangelicals, a newly identified bloc when Reagan ran for president in 1980, and it also appealed to Roman Catholics, Mormons, conservative Jews and libertarians. Its sanctification of America and its vindication of family values were a positive outward-facing message. But the president’s policies and the reverend’s rhetoric revealed a DNA that was racist, sexist, jingoist and opportunistic. Reagan’s smooth demeanor took the edge off the message’s ultimate aims, but his words and actions made plain his vision for a nation that bestrode the globe with might, right and white privilege.

Reagan truly believed that his notion of freedom—democracy, free markets and religious liberty—was God’s plan for America. He also believed that America was God’s tool for spreading freedom worldwide. In the years following his presidency, his vision was enacted through domestic and foreign policy. Welfare reform, trade agreements, and the War on Terror may have seemed to further neoliberal or neoconservative aims. But they also fit with Reagan’s notion of a Godly America that believed its self-interest was in tune with the divine.

Trump personifies this vision of freedom; he has pursued his own ends with the zeal of one who expects God is on his side. Trump both embodies and caricatures the freedom that Reagan and Falwell esteemed; he feels free to revise the truth, promise the moon, and edit the facts of his life. He also feels free to say whatever pops into his mind. His subsequent litany of misogynist, nativist and false statements, compounded by his professional failures and personal foibles, caused pundits to wonder how his campaign could rally evangelical support. Yet Trump is the quintessence of a certain evangelical vision.

Trump is a family man. Despite his lapses (and who among us doesn’t have some lust in our hearts), he is head of traditional family and supports his wives and children.

Trump is an economic success. Notwithstanding news stories about tax evasion, bad business decisions, and unpaid contractors, Trump says he a billionaire. His name is a brand, he had a successful TV show and he lives large.

Trump is a patriot. He wants America to be great again, he will put America first and he knows who the real Americans are.

Trump is a Christian. Trump may not be an exemplary believer, but he says he is one—and scores of ministers, rabbis, priests and pastors agree.

The 2016 election will be sliced and diced for years to come. We will debate whether the outcome was due to sexism, racism, economics, health care, anti-globalization, Clinton’s campaign decisions, anti-incumbency, and a host of other reasons. But let’s not forget the role of religion. And let’s not assume religion, in its evangelical Christian form, is a Sunday-only, simple piety, scripturally unsophisticated business. Conservative evangelicalism, like all other forms of religion, is entwined with all aspects of human existence.

Religion is a vision that encompasses politics, economics, nationalism, gender, and race. Religious people don’t vote based on a candidate’s support of the Ten Commandments; they support candidates who promise to inch the world closer to their own vision of what should be.

Ronald Reagan empowered religious conservatives, many of whom were white, working class and disenfranchised after the recessions and economic upheavals of the 1970s. He told them that they counted and that, thanks to God’s blessing of freedom, their futures would be brighter than their pasts. He promised them morning in America. Today, those who long waited for that dawn are finally seeing its orange tinge.

Diane Winston is a university fellow with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.