This article originally appeared on The Conversation.

A heaping plate of partisan politics, sprinkled with religious faith, topped the menu at the 68th National Prayer Breakfast.

On the morning of Feb. 6, President Donald Trump surprised listeners by eschewing traditional themes of unity, humility and reconciliation. Instead he called out “dishonest and corrupt people” who tried to “destroy” him and “hurt” the nation.

And though he did not name Sen. Mitt Romney, who voted for one article of impeachment, and U.S. Rep. Nancy Pelosi, who steered the impeachment effort through Congress, the president lashed out at those who he believes use religion to justify hypocritical actions. Romney, a member of the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, said his religious faith prompted his vote, and Pelosi, a Roman Catholic, said she prays for the president.

An annual Washington, D.C. event, the National Prayer Breakfast is an opportunity for new friends and old associates, from 50 states and 140 countries, to break bread and forge fellowship in Jesus’ name. As a scholar of American religious history, I follow the annual the get-together because I am intrigued by how political leaders approach religion.

Convened on the first Thursday in February, the gathering, known as the Presidential Prayer Breakfast until 1970, has always included the American head of state.

Trump, putting his personal stamp on the event, has used it to praise his accomplishments, malign his enemies, and thank God for being on his side.

Faith first

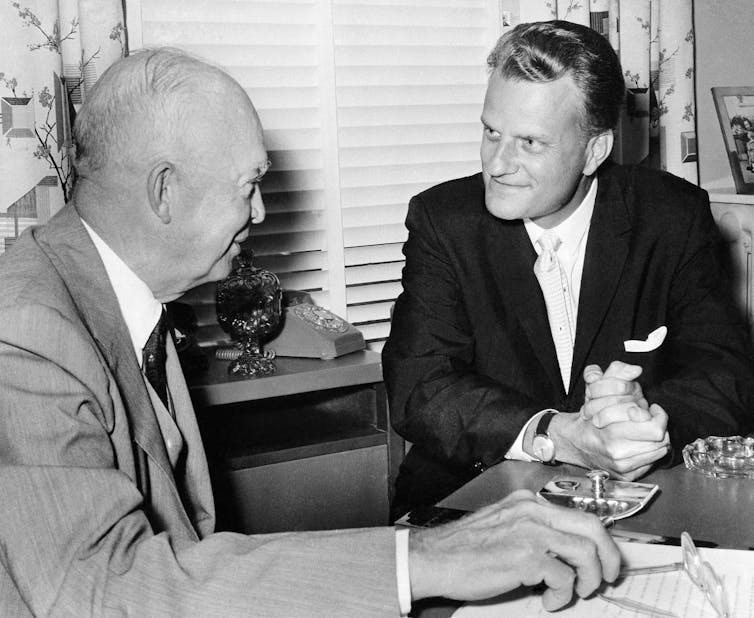

President Dwight Eisenhower began the tradition with the first breakfast in 1953. While Eisenhower was initially wary of attending a prayer breakfast, evangelist Billy Graham convinced him it was the right move.

Speaking to an audience that included Graham, hotel magnate Conrad Hilton and 400 political, religious and business leaders, Eisenhower proclaimed that “all free government is firmly founded in a deeply felt religious faith.”

Today, “Ike” – the 34th president’s nickname – is not remembered as being deeply religious.

However, he was raised in a pious household of River Brethren, a Mennonite offshoot. His parents named him after Dwight Moody, a famous 19th-century evangelist who likened the state of the world to a sinking ship and stated,

“God has given me a lifeboat and said … ‘Moody save all you can.”

AP Photo/Ziegler0

Soon after his election in 1952, Eisenhower told Graham that the country needed a spiritual renewal. For Eisenhower, faith, patriotism and free enterprise were the fundamentals of a strong nation. But of the three, faith came first.

As historian Kevin Kruse describes in “One Nation Under God,” the new president made that clear his very first day in office, when he began the day with a preinaugural worship service at the National Presbyterian Church.

At the swearing in, Eisenhower’s hand rested on two Bibles. When the oath of office concluded, the new president delivered a spontaneous prayer. To the surprise of those around him, Eisenhower called on God to “make full and complete our dedication to the service of the people.”

However, when Frank Carlson, a senator from Kansas, and a devout Baptist and Christian leader, asked his friend and fellow Kansan to attend a prayer breakfast, Eisenhower – in a move that seemed out of character – refused.

But Graham interceded, Hilton offered his hotel and the rest is history.

A strategic move

It is possible that Graham may have used the breakfast’s theme, “Government under God,” to convince the president to attend. Throughout his tenure, Eisenhower promoted God and religion.

When he famously said to the press, “Our government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is,” he was not displaying a superficial attitude to faith. Rather, as Ike’s grandson David Eisenhower explained, he was discussing America’s “Judeo-Christian heritage.”

The truth is, Ike was a Christian, but he also was a realist. Working for a “government under God” was more inclusive than calling for a Christian nation. It also was strategic. Under his watch, the phrase “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance, and “In God We Trust” imprinted on the nation’s currency. But legitimating the National Prayer Breakfast was a signature achievement.

A guide for the powerful

The prayer breakfast’s success would have pleased Abraham Vereide, the Methodist minister behind the meetings. Vereide immigrated from Norway in 1905 when he was 19. For many years, he ministered to the down and out – society’s cast-offs.

He started Goodwill Industries in Seattle and provided relief work throughout the Depression. But seeing how little progress he’d made, Vereide turned his attention from helping the poor to guiding the powerful.

According to author Jeff Sharlet, Vereide’s ultimate goal was a “ruling class of Christ-committed men bound in a fellowship of the anointed.” A fundamentalist and a theocrat, he believed that strong, Christ-centered men should rule and that “militant” unions should be smashed. Between 1935 and his death in 1969, he mentored many politicians and businessmen who agreed.

During the 1940s, Vereide ran small prayer breakfasts for local leaders and businessmen in Washington, D.C. The groups were popular, but he wanted to spread and enlarge them. Sen. Frank Carlson was Vereide’s close friend and supporter. When Eisenhower, the first Republican president since Herbert Hoover, was elected, Vereide, Graham and Carlson saw an opportunity to extend their shared mission of nurturing Christian leaders.

Using the breakfast moment

In the years since, presidents have used the prayer breakfast to burnish their image and promote their agendas. In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson spoke about the harrowing days following John F. Kennedy’s assassination and his desire to build a memorial for God in the nation’s capital.

Richard Nixon, speaking after his election in 1969, said that prayer and faith would help America’s fight for global peace and freedom. In 1998, Bill Clinton, faced with allegations that he had a sexual relationship with a White House intern, asked for prayers to “take our country to a higher ground.”

But while presidents have been cautious about their prayers, preferring generalities to specifics, keynote speakers – who are not announced until the morning of the event – are forthright.

In 1995, Mother Teresa condemned abortion as President Clinton, who supported women’s right to choose, quietly listened. In 2013, pediatric neurosurgeon Ben Carson castigated the nation’s “moral decay and fiscal irresponsibility” while President Barack Obama sat in the audience.

More changes with time

In 2017, his maiden appearance, Trump broke precedent with a powerful no-holds-barred speech that put other countries on notice, threatened church-state separation and mocked actor Arnold Schwarzenegger. At the time, his performance stunned listeners who expected the breakfast to be a staid event.

This year, Trump again had his say at the morning meeting. Supporters tuned out his vitriol and focused on his example of strong Christian leadership.

“We know that our nation is stronger, our future is brighter, and our joy is greater when we turn to God and ask him to shed his grace on our lives,” Trump said. “On Tuesday, I addressed Congress on the state of the Union and the great American comeback. That’s what it is. Our country has never done better than it is doing right now.”

This is an updated version of an article first published on Feb. 1, 2017.

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Diane Winston is a university fellow with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.