“Religion is personal but it isn’t private,” says Rev. Dr. Cecil “Chip” Murray in a typically pithy summary of belief capturing a tension that shapes the lives of individual Christians as well as the loosely confederated group of religious movements collectively called the black church.

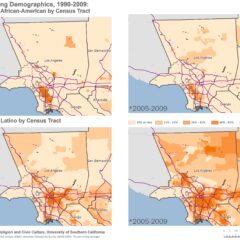

Murray joined the faculty of USC in 2004 after retiring from his post as pastor of First African Methodist Episcopal Church (FAME). During his quarter-century at FAME, he transformed a congregation of a few hundred into an 18,000-member mega-church with multi-million dollar community and economic development programs that brought jobs, housing and corporate investment into many South Los Angeles neighborhoods.

His association with the PTM program as a senior fellow at the Center for Religion and Civic Culture has been essential to attracting participants, many of whom cite the opportunity to work in a mentoring relationship with Murray as a key reason they decided to enroll. But a selfinterested desire to emulate Murray’s success as a church-builder—particularly if that impulse is tinged with the materialism of the Prosperity Gospel—is a setup for disappointment.

“I would admonish those who preach prosperity to remember that the one who founded the Christian church had just one pair of sandals for his feet,” Murray says.

In Phase I of the program, which usually occurs over two days at the end of June, students have their visions of the social role of the church and faith leaders challenged and reformulated. The two-fold purpose of this mindset reorientation is to counter the institutional paralysis that often prevents African-American congregations from responding effectively to the urgent needs of their communities as well as the near-term focus on personal prosperity that PTM’s directors see as a betrayal of the spirit of their movement.

“We believe Christ came to set the captives free,” says Mark Whitlock, “to bring sight to the blind, to clothe the naked, to find shelter for those who are looking for housing. That’s the work of the church. We have to return to the values that made the black church an agent of positive social change.”

Still, there is often a tension between that goal and the desire of some participants simply to bolster their own membership rosters. A handful of students have left the program at this early stage, though the PTM staff say they are careful to establish that while their purpose is not to equip participants to build a personal pastoral empire, they are committed to helping students do the hard work of spiritually rigorous civic engagement.

“They can expect an experience that’s academic, theological as well as political,” says Eugene Williams. “But not political in a partisan sense. We try to help people to think differently about the world and their faith and to use that new thinking as a way to expand the public square.”

Mentoring Change

The clarification process that underlies Phase I of the PTM program includes presentations on the nuts-and-bolts of community development and policy advocacy as well as the theological and historical impulses that inform PTM’s mission. Equipped with this theoretical introduction to civic engagement, participants are then divided into clusters and assigned mentors from the PTM staff.

As they begin to shape their ideas for the projects that will be the focus of their written and on-the-ground work during the next phases of the program, students are encouraged to see both their mentors and the other members of their cluster as resources to help them assess and address the needs of the wider communities their congregations serve. In a practical sense, this emphasis on collaboration encourages participants to cultivate the kinds of skills and relationships that will allow them to sustain and build social capital over the long term. It also reinforces the premise that civic engagement is integral to the history and vision of the black church.

“This part of the program gave me a clear understanding that I can be a part of civic life without jeopardizing spiritual gifts,” says Robert Rubin, an alumnus of the PTM program in 2007 and executive director of the Crenshaw Christian Center’s Vermont Village Community Development Corporation, which works to seed affordable housing, business investment and home ownership in L.A.’s Vermont-Manchester corridor.

“It’s not a social service perspective versus a salvation perspective,” Rubin says. “People have to be saved in order to be changed, but the church has also been an organization that is socially oriented to do the right thing in the community.”

Reigniting Embers

About a month after their introduction to the PTM program, fellows meet for Phase II, a sixday residential intensive that deepens their relationships with mentors and peers in their cluster, who become key resources for trouble-shooting and inspiration as each participant is pushed to develop her or his plans for civic engagement more fully. PTM staff members expand on the community development and policy-oriented components of Phase I, and guest speakers— from prominent scholars like Lawrence Mamiya of Vassar College and public theologians like J. Alfred Smith to seasoned veterans of state and local politics—further illuminate the close connections between activism, history and applied theology in the black church.

“The speaker that stuck out in my mind was Dr. Aldon Morris,” says 2010 PTM alumnus Marcus Farrow, a lay leader at New Dawn Christian Village, where he co-founded a faith-based youth mentoring program to help keep ado- lescent and teenage boys out of the criminal justice system. Morris, a professor of sociology and African-American studies at Northwestern University, outlined larger trends that Farrow sees playing out in the lives of the young men he works to shepherd through an often treacherous cultural landscape.

“There has been a tendency to say that there has been advancement in overall systemic attitudes about race in America,” Farrow says. “People like Oprah Winfrey or Michael Jordan are used as examples of progress in a situation that I don’t think has progressed that much. And having a black president has started this post-racial discussion—like we’ve gotten past something that I don’t think is really behind us.”

Morris’s lecture impressed on Farrow not only the importance of a clear-eyed view of the present but also the urgency of learning the skills needed to effect change.

“It was like embers being reignited,” says Farrow, who has spent two decades in the mortgage and banking industries. “It all goes back to interests”—personal and commercial as well as political—“and capital formation and access to credit. That’s the connection I needed to make.”

Building Human Infrastructure

Before she enrolled as a PTM fellow in 2010, lawyer and educator Lydia Hollie says that while she felt pulled to express her faith through the violence-prevention work she was doing with the Long Beach Human Relations Commission, she was at a loss for a conceptual framework that would allow her to integrate her on-the-ground activism with the spiritual life of her community at the Greater Open Door Church of God in Christ, where she serves as director of public affairs. The penny dropped for her during Phase III of the PTM program, a three-month practicum during which students hone their formal plans for future civic engagement projects and continue to work with the members of their mentoring clusters to meet the day-to-day challenges of leadership.

“I realized that what I was doing to try to shut down the pipeline to prison was the same as what was going on inside the church on Sunday,” says Hollie, who also studied as a fellow at CRCC’s Institute for Violence Prevention. “Community work is sanctuary work. That was the real ah-ha moment for me.”

Bolstered by her ongoing consultation with mentors and peers, Hollie began to broaden her relationships with key stakeholders in the Long Beach neighborhoods where she saw young people were at greatest risk. The confidence that she had professional and spiritual resources to match the needs she wanted to address prompted another revelation.

“It’s all about knowing where to start,” she says. “We often think of community development as bricks and mortar, or policy work as building the legitimacy of an issue. That’s true, to an extent. But in my mind, especially through my experience with PTM, both of those things begin with the development of human infrastructure. Real community change starts by having conversations with the people who are in it.”

Download a PDF of the report

Nick Street was a senior writer with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.