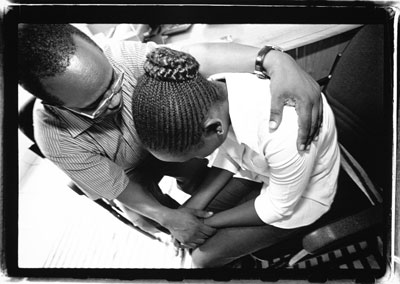

The hero image of religious saints involved in humanitarian work warrants examination.

I have come to this conclusion in the process of leading a global project on “spiritual exemplars” at USC’s Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

At one level, the roots of humanitarian compassion are as old as humankind, if defined as willingness to care for those in need. But the first use of the term “humanitarianism” occurs in the early 19th century and escalated dramatically in the 20th century, fueled by technology and media as individuals witnessed famine, genocide and natural disasters beyond their national boundaries. Organizations such as the International Red Cross, Oxfam, Save the Children, CARE International and Médecins Sans Frontières became household names. Simultaneously, a number of religious non-governmental organizations (NGOs) also appeared: Catholic Relief Services, World Vision, Lutheran World Relief and Islamic Relief.

Initially, many of these organizations were crisis oriented, but in time they realized that long-term development projects were necessary, rather than simply shipping food, tents and blankets to alleviate immediate suffering. Agencies became aware that aid could result in dependency over the long term and that dealing with the root causes of suffering was important.

Various ethical principles emerged for both secular and religious humanitarian groups, including “Do more good than harm,” taking a chapter from medical ethics. In addition, various Enlightenment values became central, including impartiality (intervention regardless of race, ethnicity, class or nationality), the dignity of all persons, and the view that all individuals are worthy of respect. Secular and religious organizations shared a common transcendental view that there are values larger than oneself and one’s own tribal group — even though the stories told to justify these views differed. Secular entities might appeal to universal values, while religious groups refer to notions of duty: Zakat for Muslims; Tzadakah — “repairing the world” — for Jews; the story of the Good Samaritan for Christians; dana for Hindus and Buddhists.

Countering the sanctimonious spirit of humanitarian work was a Marxist critique that efforts to bind up the wounds of the distressed indirectly perpetuated their suffering within a capitalistic world order. Humanitarianism, like religion for Karl Marx, was part of the superstructure of society that smoothed over social grievances and thereby contributed to the development of bourgeois society. In the words of Michael Barnett, a historian of humanitarianism, “Global capitalism needs humanitarianism.” While aid workers appear to be emancipatory, they are actually agents of social control.

More recently, another critique has emerged, although it may simply be an attempt to blunt the halo status of notable humanitarians such as Mother Teresa, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King or Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Namely, humanitarianism serves the needs of the giver as well as the receiver. In a study of Finnish Red Cross workers, the anthropologist Liisa H. Malkki said that serving in distant countries provided an opportunity for travel, living an exciting on-the-edge existence that mundane social service work did not. She applied this argument even to women who knitted blankets for children in impoverished countries—a transnational act that gave them a sense of purpose in life.

Both of these perspectives—the Marxist and the self-interest view—warrant consideration. However, during the last five years of studying exemplary humanitarians who are inspired by their religious faith and practice, I have a more complex response than might be achieved from an armchair vantage point. For example:

Dr. Tom Catena has spent almost 20 years in a rural part of Sudan where he works 24/7 running a hospital that serves thousands of people each year. He sees up to a hundred patients a day and does surgery multiple days a month. In some ways, he is an unlikely Catholic missionary doctor. At Brown University he was an all-star football player majoring in engineering. During his senior year, in part influenced by a mentor at a Christian organization on campus, he decided to go to medical school. He enrolled in the Air Force so that his medical school tuition would be paid.

His decision to buck the traditional path he could have followed may have satisfied some underlying desire for adventure and travel, but if it did, that motivation wore out quickly. His continual decision to stay, even as bombs were dropping around the hospital, was much deeper. In Tom’s view, following Jesus, who ended up on a cross, is not an easy path. He says the goal of life should be joy, not happiness — and he finds great meaning and purpose in his work.

Jean Bouchebel is another example of someone who had a complete change of life and orientation. He grew up in Lebanon in an orphanage after his father died. As a young man, he worked his way up from a bus boy to a management position at an exclusive hotel. In his early 30s, he felt empty inside and had a life-changing conversion experience in an Evangelical church. After multiple challenges because of the civil war in Lebanon, he was asked to lead the relief work of World Vision in Lebanon and surrounding countries. On his retirement from World Vision, he then started his own organization to serve the many Syrian refugees in Lebanon, working with local churches.

In our project on Spiritual Exemplars, there are multiple pathways to engagement with humanitarian work. For some, it is nearly accidental. Julie Coyne, for example, responded to a need, serving poor children in Guatemala, and years later continues running an expansive program for preschool children, some who end up going to college. For others, like Dr. Catena, the path was more linear and intentional. And for others, such as Jean Gakwandi in Rwanda, it was a political crisis — the Rwandan genocide — that called him to the work of healing and reconciliation after most of his extended family was killed in 1994. For Sister Rosemary Nyirumbe, it was children seeking refuge at her convent during a civil war in Uganda that led her to develop an extensive training program for girls.

Does their humanitarian work give them meaning and purpose? Absolutely.

Does this diminish the human good they are doing? Not at all.

To argue the latter would be to engage in reductionist thinking, a type of utilitarian logic that one’s actions and life choices are based solely on what one receives in return. In the cases just mentioned, each individual has a profound faith in what Sister Rosemary calls a “provident” God — a God who cares and provides. Without this faith, a belief in what William James refers to as an “unseen” reality, they would not live with hope and purpose.

But what about the Marxist critique? Are they simply putting bandages on wounds that would better be dealt with through social revolution?

This is a legitimate question and one that has preoccupied Catholic theologians and social reformers who embrace “liberation theology.” Abstractly, Marx offers a tantalizing viewpoint. But in concrete practice, it is difficult to ignore the human good done by Dr. Catena in his clinic and hospital, measured by the people cured from leprosy, the babies born with good prenatal care, the people stitched up after bombs were dropped on their village by the Khartoum government. Likewise, the traumatized people who found healing at Solace Ministries, which was started by Jean Gakwandi, give witness to the role of intervention. The Syrian refugees fed, given jackets and fuel to make it through the brutal winters in the mountains of Lebanon would dismiss the Marxist viewpoint. Or the girls who were raped by members of the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda, and found healing and hope in Sr. Rosemary’s school are testimony to the value of someone taking up a challenge.

Humanitarianism is a complex topic and religion is intertwined in it. Historian Michael Barnett states, “Religious agencies can take credit for pouring the foundations for humanitarianism. . . . Throughout history, religious, spiritual and philosophical commitments have inspired acts of compassion.”

What is often ignored in the discussion, however, are some of the complexities and challenges of religiously inspired humanitarianism. For example, the sexual abuse linked to some humanitarian efforts and individuals. The compromises in family relationships required by individuals who give themselves unstintingly to their work. The toll on humanitarians of vicarious trauma as they encounter poverty and disaster on a daily basis.

Nevertheless, religious humanitarians have oftentimes been social innovators and entrepreneurs, even though they typically are operating within the “iron cage” of capitalism. Historically, they have been at the forefront of human rights issues. They have been models of living a purposeful and meaningful life, inspiring emulation and hope in a transcendent moral order.

Life is filled with complexity and religion is no stranger to it.

Donald E. Miller is the co-founder of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.