Accounts of the Hong Kong campaign for political choice and universal suffrage that began in late September have emphasized the prominence of Christian activists in planning and leading that movement. Community organizer Samuel Chu points out that Christians have in fact been divided over the protests: Older churches that were founded by missionaries during the colonial period and whose activities were generally aligned with colonial priorities have not taken the lead, and more recent churches affiliated with conservative evangelical groups are similarly cautious about activist participation in the public sphere. On the other hand, Chu notes that for socially engaged churches and “outlier” Christian clergy and academics there is a direct moral connection between the belief that “Jesus loves everyone equally” and the demand for equal participation in the political, social and economic life of the community.

Some reports have reflected a degree of surprise at this convergence of religious and secular impulses, but historically the practice of Christianity in China has often involved the interplay of religious conviction with civic activism. To take one case in point, recent events in Hong Kong display striking similarities to public responses to the so-called “Shameen Incident” of June 23, 1925. On that that day in Guangzhou (then Canton), a very large and diverse assembly of Chinese nationalist demonstrators converged on the European commercial establishment on Shamian (“Shameen”) Island in the Pearl River. They came to protest a confrontation that happened in Shanghai three weeks earlier, when British security forces killed several Chinese protesters, including some students, who were challenging labor conditions in areas controlled by Europeans.

In the subsequent event in Guangzhou, armed cadets from the nationalist Whampoa Military Academy were among the demonstrators. Whether British security forces were provoked by these cadets is unclear, but in the course of the confrontation, one European and as many as 50 demonstrators, again including students, were killed. A protest parade through the city, focused on the humiliating “unequal treaties” that protected European commercial interests in China, followed as an immediate reaction. For weeks afterward a growing mass movement produced strikes that enveloped the entire region, the British crown colony of Hong Kong included.

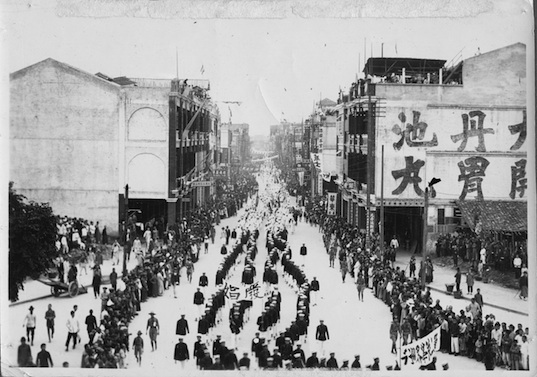

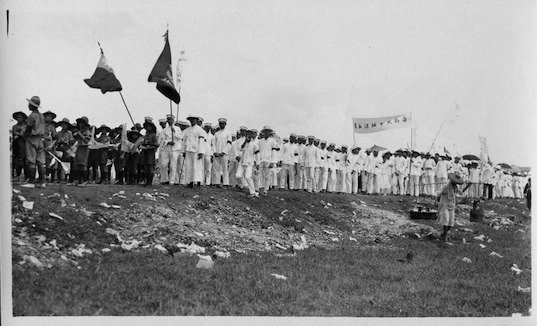

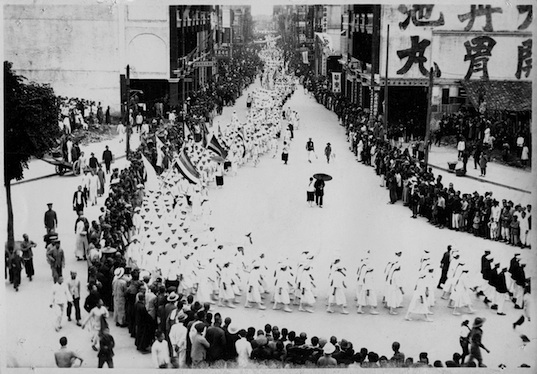

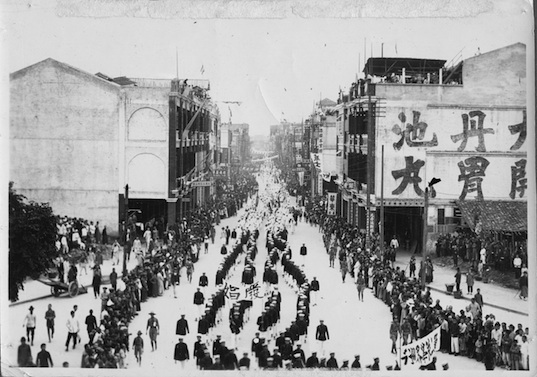

Outwardly these events from an earlier time, like those in Hong Kong today, appear to be essentially secular, but photographs of the Guangzhou march taken by missionaries provide a substantially different perspective. These images and their accompanying archival descriptions are preserved in the Day Missions Library of the Yale Divinity School and are accessible online through the International Mission Photography Archive, developed jointly by CRCC and the USC Digital Library. The six images reproduced here show that disciplined Christian protesters from missionary-founded Canton Christian College (later known as Lingnan University), were conspicuously present in those demonstrations, coming together in a de facto alliance with prominent secular politicians, Soviet advisors from Russia and nationalist military cadets.

The first photograph shows the assembly of Canton Christian College students before the parade in Guangzhou began. Picture notes indicate that they were gathered for a motivating speech by a nationalist (Kuomintang) politician characterized in the record as an “ultra ‘Red’.” This man, Liao Chung Kai, is the central subject of the second picture, where the notes indicate that he was assassinated soon after the picture was taken.

1. Students at protest parade, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, 1925

2. Liao Chung Kai at parade, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, 1925

The striking third picture below is accompanied by these notes: “Canton Christian College Boy Scouts and Students forming for parade and demonstration in Canton, off Shameen, the foreign concession, June 23. The arm bands of mourning are being worn for the students slain by British police in Shanghai, May 30.”

3. Students and Boy Scouts at protest parade, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, 1925

Female and male students, in uniform and marching precisely (albeit separately), dominate the next two pictures:

4. Female university students in protest parade, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, 1925

5. University students in protest parade, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, 1925

Finally, in the last picture, a contingent of conspicuously armed military cadets who shared the parade route with the students appears with this revealing description: “Whampoa Military cadets on the parade grounds in Canton City previous to the parade off Shameen, the foreign concession, June 23. This group [was] the only armed part of the parade, and it is claimed by the foreigners that they fired the first shots which led the Shameen [European] side to open fire on the paraders. It is said that these cadets are under Russian leadership. They played a large part in defeating the Yunnanese in the middle of June. Newspaper reports have recently said they have gained control of Canton City.” [The banners read:] “We demand immediate abolition of foreign settlements. Abolish extra-territoriality.”

6. Military personnel in parade, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China, 1925

Acknowledging the precedent set by these determined Christian students and Scouts in Guangzhou in 1925 helps to put the civic activism of Christian youth in Hong Kong in 2014 into a broader perspective. Both episodes, then and now, exemplify the unintended and often unanticipated secular consequences of religious change. If the conviction of religious equality has been internalized, some will simply find the imperatives of that conviction impossible to reconcile with social structures that support economic inequity and political repression. The energy of indignation produced by this reasoning, however politely it is displayed, is likely to resist confinement to approved channels of expression and participation. There is irony in the fact that the 1925 protests sought to end British influence in China, while the current demonstrations seek a measure of independence from the Beijing regime that displaced the British in 1997.

Jon Miller is a guest contributor and formerly a senior research associate with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.