There is a great boom in psychotherapy these days. Especially among a younger generation, people are lonely, anxious about the environment, insecure financially—fearful they will not achieve the same standard as their parents—and burdened with choice, about their gender, vocation and life commitments.

Among young people, the meaning crisis is inversely correlated with kids having sex, going to church and experiencing face-to-face community, all of which are on the decline. And it is positively correlated with rising rates of teen suicide, anxiety attacks and depression. In his recent article in The Atlantic, David Brooks describes our current state as an “emotional, relational and spiritual crisis.”

“Teenagers are Telling Us that Something is Wrong with America,” read the title of a New York Times piece. The teen years have always been a period of identity confusion, the author explained, but something more is going on today. The guardrails of meaning-making have lost their poignancy. And in this void, people are seeking out therapists as moral guides, surrogate mentors and spiritual counselors.

I have no doubt that therapy can be useful in many situations, although in the same issue of the New York Times, an article asked the question, “Why Do People Think Going to Therapy Makes You a Good Person?” The subtitle responded: “The recent focus on therapy as a cure-all overlooks that there are other ways to heal.”

In any cultural crisis, there is not one solution, one cure-all. Personally, I doubt that we are going to turn the clock back on technology. Nor are young people going to find their way back into institutional religion. And shutting down a woman’s ability to choose or banning gender choice will not solve our cultural crisis of meaning.

Instead, I want to offer a small, very modest proposition: We need more awareness of moral heroes in our lives.

And by that, I don’t mean political gurus of the MAGA sort. Rather, people who have earned their stripes through a deep commitment to humanitarian work.

In this regard, I have been privileged to direct a project at the University of Southern California that told the stories of 104 exemplary people around the world who are involved in health care, poverty reduction, climate change and various interventions on behalf of vulnerable people. We are pleased to be sharing these through a new exhibit at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

In sifting through thousands of pages of interview transcripts with these individuals, I found several characteristics that make these living heroes models for people—young and old—who want meaning and connection in their lives.

First, they are purpose driven. For some, they are following a religious calling. For others, there was a crisis in their life or an event, such as a natural disaster or genocide, to which they responded. And some became involved in a life-long commitment to social justice in an almost accidental way—they encountered children in need or a situation that demanded a response.

Second, they are counter-cultural, not in a hippie sense, but in a way that sets them against the stream of material values, social norms and often political ideologies. They find freedom, not in accumulation of wealth or possessions, but in meaningfully doing something daily, whether it is caring for people with AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa or advocating for Indigenous rights in Alaska.

Third, they have an indomitable spirit in service of the challenge they are addressing. This grit is rooted in a deeply held set of values and is nurtured daily in a set of spiritual practices that may involve prayer, meditation (or silence) and corporate worship. They understand that burnout is a liability of their work if they do not retreat on a regular basis into some form of communing with a higher power than themselves.

Rather than turning inward, they have found identity, meaning and purpose in serving others, in journeying outward. This does not mean that they have not faced their own demons. And it certainly does not mean that their lives are without struggle. But they have learned to “let go” in the act of meditation so that they can follow a practice of “engaged Buddhism.” Or, if Catholic, to spend an hour of adoration and prayer every noon so they can continue providing health care the rest of the day and into the evening.

While there are saints and heroes of the past—Gandhi, Mother Teresa, Martin Luther King—there are multiple contemporary exemplars, such as Greg Boyle, who runs a remarkable program in Los Angeles for ex-gang members and recent inmates. Fr. Greg is up every morning at 2:45 am as he begins his day at a home altar in his room, gaining perspective on a full schedule of meetings with homies who are seeking a way out of violence and abuse.

While therapy can help one sort through traumatic life experiences, profound meaning comes in uniting with a purpose higher than oneself. This is where we need models of exemplary people that we can emulate—hero figures.

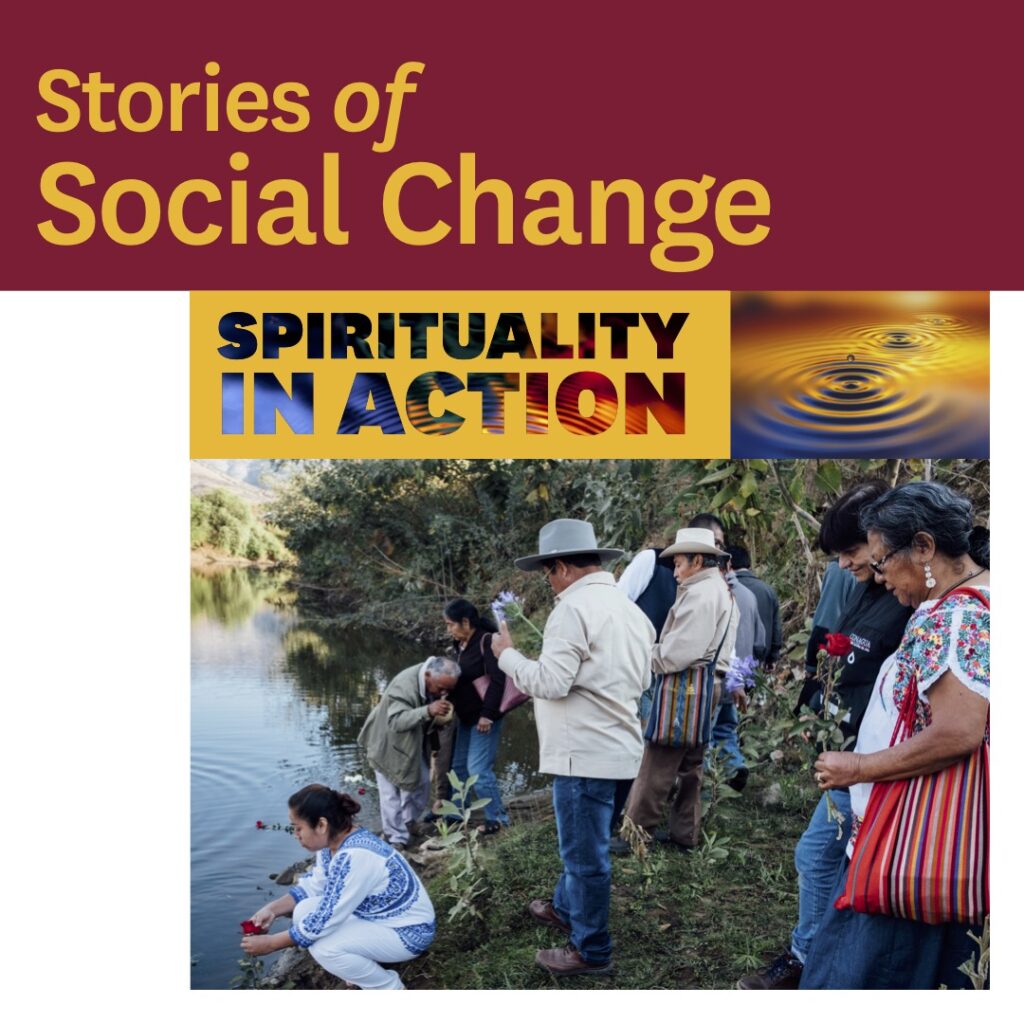

As USC launches the Fall 2023 semester, photographs of some of the 104 heroes we profiled as part of the “Spiritual Exemplars” project now grace the walls of Wallis Annenberg Hall (ANN) at USC. As they go to class, students will see people of all faiths—and none—in contemplation and action, and read quotations from their interviews with our journalism fellows.

We hope that the “Stories of Social Change: Spirituality in Action” exhibit provides inspiration to future journalists at USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism to keep on telling these stories. Heroes can be found in great literature and in inspiring movies. And as our journalism fellows showed us, there are countless heroes all around us. Their stories—told in articles, videos and podcasts—can inspire readers, viewers and listeners.

We also hope that the pictures, quotes and “stories of social change” might provoke those who walk through the exhibit—or glance at an image on the way to class—to consider how they can build a meaningful life, rather than worry about their grades or how to land the most prestigious internship.

Three moral exemplars will join us for a panel and reception on Tuesday, September 12: Father Greg Boyle, Sabrina Sojourner, and Brother Phap Dung, who was once a USC student himself.

All are welcome to join us for an evening of inspiration.

Exhibit Information:

Stories of Social Change: Spirituality in Action

Wallis Annenberg Hall (ANN)

Open to the public

Visit the exhibit website

Reception

Tuesday, September 12

4:30-7:30 pm

Tour the exhibit starting at 4:30, panel at 5:30 and reception to follow

Click here to RSVP

Donald E. Miller is the co-founder of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.