This post originally appeared in Zócalo Public Square.

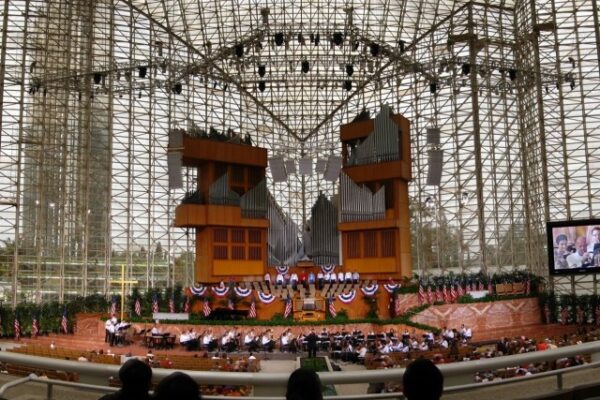

If this year were like years past, the Crystal Cathedral, the Philip Johnson-designed Protestant megachurch in Garden Grove, would be abuzz with the “The Glory of Christmas” pageant, with angels suspended from ropes and with a parade of camels, horses, sheep, and donkeys. Not so this year. Bankruptcy is dampening the holiday spirit at the institution that once embodied the megachurch movement in the United States, and the pageant is off. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Orange has put up the cash to take over the Crystal Cathedral.

The Crystal Cathedral is certainly among the most famous megachurches in the world, but it is just one of many. Los Angeles and Orange counties have nearly 80 megachurches. They range in congregation size from 2,000 to 25,000 and include all races and ethnicities. In all, they claim over 350,000 congregants. The question, now, is what the demise of the Crystal Cathedral may portend for megachurches more generally. Was this simply a story of changing demographics in Orange County, which has become more racially and religiously diverse? Perhaps. But it’s also possible that the megachurch model is, ever so slowly, going into eclipse.

Megachurches like the Crystal Cathedral have become successful by doing two things really well. First, they use professional-quality entertainment and familiar (and often secular) cultural themes in their services to make their members more comfortable. Second, through these programs, megachurches have turned themselves into a destination for their members on days besides Sunday, and this creates a distinct sense of community. One result has been the creation of a huge market in Christian consumer goods like T-shirts, hats, bumper stickers, and music. The church grounds are often campus-like, with bookstores, public gathering areas, and food courts–which of course serve Starbucks coffee.

Yet this large-scale consumerist model also entails immense costs: not only employees to run and track the many ministries and programs but also maintenance of the physical plants that support all these activities. Just think, for example, of the cost of maintaining a building made entirely of glass.

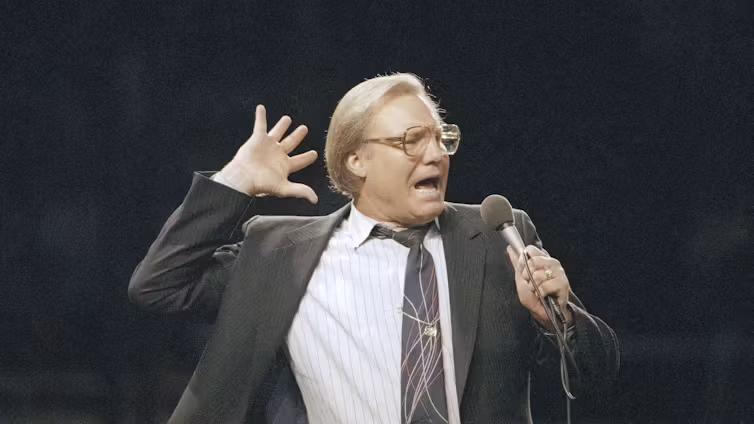

For this reason, megachurches cannot easily withstand drop-offs in attendance or membership, and they are compelled to compete with each other for religious market share. Who has the most members, offers the widest array of programs, and produces the glitziest Christian-oriented media? This “keep building, keep growing” mindset necessitates more and more new programs and products to keep attracting new members. The results are often a form of “religiotainment” for seekers, and, whether the product is Christian-oriented positive thinking (“possibility thinking” in the parlance of the Crystal Cathedral’s Robert Schuller), T-shirts, CDs, or bumper stickers, the goal is to get people into the pews and make them want more.

Unfortunately for the megachurches, congregants have not always wanted more. Over the past decade, the megachurch model has been showing signs of giving way, slowly, to a more intimate spiritual culture. Some megachurches have even tried to accommodate this apparent trend by creating multi-site churches to give the impression that they are smaller than they actually are. The new form of religious infrastructure manifests itself in churches that focus less on physical sprawl than on cultivating what they call a more “organic” understanding of religious organizations. The new communities are expected to have a birth, life, and–yes–even death.

These are generally (not always) smaller groups that rent space for their weekly worship services and spend a lot of time creating a spiritual and physical community of mutual care. They don’t put on big, highly produced pageants to draw in the masses; instead, they create space for anybody to come and join in worship. They see themselves as a part of local civic life and seek to play an active part in those communities as an equal partner, sharing with others rather than imposing their programs and vision on them.

What these groups also have in common is a more democratic form of authority, in contrast to the more top-down model that characterizes most megachurches (and indeed most religious organizations). These newer groups are taking authority and leadership out of the hands of the few and putting power in the hands of the many who make up the religious community of the church.

Whether this newer model will continue to gain ground is of course uncertain. Organized religion, after all, is about authority, and democratizing it may threaten religious institutions in ways we haven’t even thought of yet. Quite possibly, some of these new movements will succumb to the inevitable temptation to create their own empires, regardless of how “authentic” they may appear. For now, a model of shared, democratic religious authority is on the ascent, and it has more in common with grass-roots political activism or NGOs than it does with a church modeled on American business culture.

Regardless of what format people choose to worship in, the biggest social contribution that religious groups can make is to lend their moral voice to the cacophony in the public square. The examples of figures such as the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Rev. Cecil “Chip” Murray, formerly of Los Angeles’ First AME, remind us that the prophetic power of religion in civic life is about more than giving us what we want. Ideally, it encourages us to engage each other in the pursuit of a just and moral society. If the form of religious community that emerges after the era of Crystal Cathedral and other megachurches embodies this potential, the real glory of Christmas may be just a bit closer to reality.

Click here to read the original article.

Richard Flory is the executive director of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.