This post originally appeared on Trans-Missions, the USC Knight Chair in Media and Religion site.

In an effort to rally evangelical support for one Republican candidate in the upcoming South Carolina primary — and beyond — “evangelical leaders,” according to the New York Times, met last Saturday to vote on who that candidate should be. Through three balloting cycles the candidates receiving the most votes were Mitt Romney, Newt Gingrich and Rick Santorum (Rick Perry, an early favorite among evangelicals, has now dropped out of the race). On the third ballot, the results favored Santorum by a factor of more than three to one.

What more needs to be said? To suggest that there are 100 or so evangelical leaders who can get together and vote on a candidate that all evangelicals will support is to believe that all evangelicals interpret their religious beliefs in identical cultural and political ways. This of course isn’t, and likely could never, be true. As with any social grouping there will always be divisions based on factors such as age, social class and the like, and evangelicals are no different from other groups in this regard. Yet evangelicals are consistently presented in news media, at least implicitly, as a monolithic cultural and political force that will march in lock-step with their purported leaders, men like James Dobson, Tony Perkins, Gary Bauer and the late Jerry Falwell.

This, however, has never been true of evangelicals, and recent evidence suggests that the evangelical movement is becoming more ragtag than ever before. As early as 1947 evangelical theologian Carl Henry was arguing for a re-engagement of evangelicals with social justice issues. In the early 1970s Jim Wallis and Sojourners began developing their social justice platform and in 1977, Ron Sider published Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger, a book that probably 75 percent of all evangelical college students have read.

More recently Richard Cizik’s excommunication from the National Association of Evangelicals over issues related to environmentalism and gay marriage–along with recent surveys showing that younger evangelicals are dissatisfied with the religion they’ve inherited and that some are starting to frame issues like care for the environment and addressing poverty much differently than their parents–suggest that more change is afoot for evangelicals. Indeed, there are even examples of evangelicals who are working as community organizers — a notion anathema to the conservative leaders gathered last weekend — and who are using their faith commitments as the starting point for efforts to help to create a better world for those who are less fortunate.

Reporters would do well to begin to investigate whether these developments—which have a much longer history within evangelicalism than just the last 5 or even 10 years—are now becoming part of a distinct movement within evangelicalism that may at some point challenge the leaders that most journalists and politicians seems to think evangelicals still have. Are the usual suspects like James Dobson, Gary Bauer, Pat Robertson and their ideological kin simply trying to hold on to some form of authority in a movement in which their time is likely up? Do the changes that appear to be happening really represent a sea change among evangelicals, and if so, will it permanently alter the course of the movement? Will younger evangelicals, as they marry and have children, begin to adopt their parents’ worldview, or will they continue to espouse the values that currently inspire them? Most fundamentally, how will notions of biblical authority evolve as the projects of this new generation begin to take root?

The results of the Republican primaries, as well as the upcoming general election, may well be decided on the vote of traditional evangelicals. Reporters should ask whether those outcomes represent an enduring phenomenon or the last political hurrah of a passing generation.

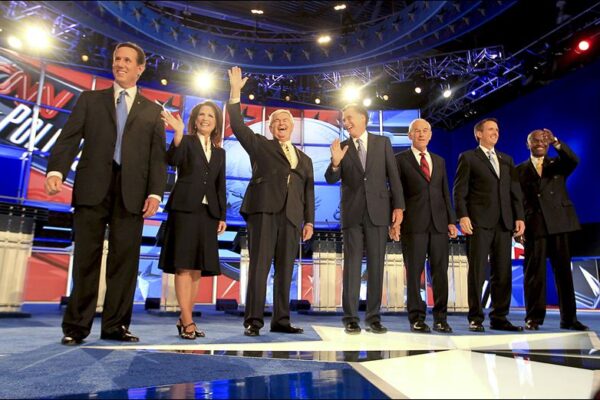

Photo from The Toledo Blade.

Richard Flory is the executive director of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.