The following article originally appear in Tui Motu InterIslands Magazine, a New Zealand publication.

One of the first survivors that I interviewed in Rwanda after the 1994 genocide told me that his Catholic priest refused to give him communion because he did not give the body and blood of Christ to a “cockroach” — which is what Tutsis were referred to by Hutu extremists.

In 100 days, beginning in April 1994, more than 800,000 Tutsis were killed by militia, but more astoundingly, by their Hutu neighbours, with whom they had previously enjoyed good relations, including being the godparents to their children.

Building Up to Genocide

How can such atrocities occur? In every instance of genocide, it is preceded by demonising the target group, making them less than human. Humans do not kill one another on a mass scale for fun; they concoct theories that justify their extermination. This is the role of propaganda: To dehumanise people so that they can be killed without ruffling one’s conscience.

In the case of Rwanda, tens of thousands of women were raped, sometimes in front of their children. And not raped once, but multiple times. One survivor told us that every man in the village knew her body.

Family structures were destroyed. The roles of mother, grandparent, sister or brother were lost when nearly everyone in the family unit was killed. Houses were destroyed, ensuring that survivors would not return. Social roles related to employment no longer existed. And for many survivors, their religious views were called into question: Where was God? Why didn’t God intervene? Did God not care about his children?

Destroying Moral Compass

Genocide is not just about death. It is a moral rupture in one’s world view, which is the basis of psychological trauma after a genocide. Nothing makes sense anymore. Indeed, in the process of interviewing hundreds of survivors, of both the Rwanda genocide and the Armenian genocide, which occurred in 1915 in Turkey, my world view was shaken. I experienced a form of vicarious trauma.

For those of us who identify with the Christian tradition, there are many questions to ponder. In the case of Rwanda, it was Christians killing fellow Christians. The only thing that separated victim from perpetrator was their tribal identification. In fact, there were more people killed in churches than any other location, because Tutsis often fled to their local church when the killing started, thinking they would be safe. But, instead, too often clergy were bystanders to the violence and, in some instances, had actually set the stage for genocide by spewing racist rhetoric in their sermons.

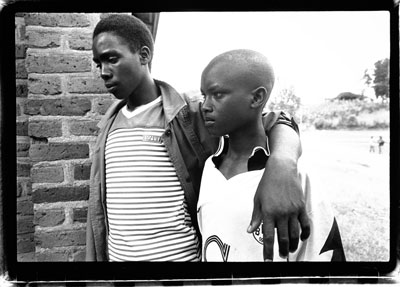

In the post-genocide period, orphans were wandering the streets; women had been infected with the AIDS virus from rapes; survivors were nursing amputations and wounds. And institutions had failed to function.

Can Religion Help Recover Personhood?

The question is whether religion can play any function in a post-genocide situation such as Rwanda. Can it help survivors regain their humanity, their sense of dignity?

My answer is ambivalent since I am troubled by the fact that most Churches, both Catholic and Protestant, did not counter the racist propaganda prior to the genocide, and only a few Hutu priests chose to die with the people of their congregations in active resistance to the killers.

Nevertheless, I would like to share my experience of Solace Ministries, a faith-based programme that emerged after the genocide in Rwanda. I believe it is a model that has lessons for other experiences of genocide, and, more generally, any situation in which large numbers of people have experienced a collective trauma.

Jean Gakwandi, the founder of Solace Ministries, lost all of his extended family in 1994, although miraculously his immediate family survived because they were sheltered in the home of a German living in Rwanda. When the genocide ended, Jean said that he felt numb, unable to feel anything. However, during the 100 days of the genocide, he read a verse from the Old Testament book of Isaiah (40:1) that kept echoing in his mind after the genocide ended: “Comfort, comfort my people, says your God.”

Comfort My People

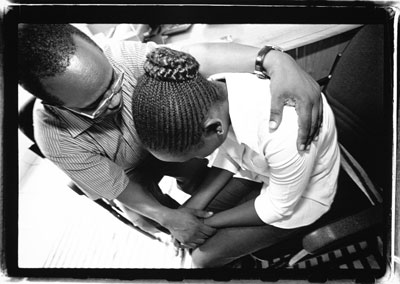

In response to this command, Jean invited some survivors to meet with him. Initially, only a handful of women came. Jean invited them to tell their stories, and he wept with them. Although a layman — an Anglican by religious background — he prayed with these survivors as they cried, comforting them and acknowledging their pain.

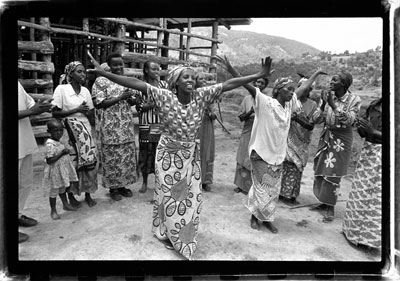

Before long, a hundred and more survivors were meeting weekly. The format that evolved was the following: Those who gathered would sing for a long time to the beat of a drum, but with no other accompaniment. Jean would read comforting passages of scripture. And then survivors would be invited to “testify” about their experience.

Telling the Story

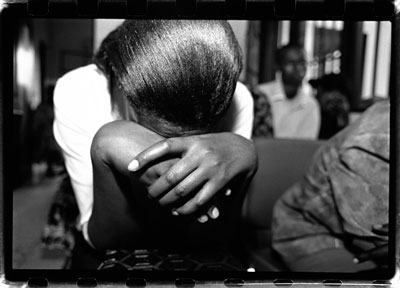

Initially, survivors would stand and choke out a few sentences about how their husbands, and often their children, were killed. They might refer to rape with a euphemism such as “the killers did whatever they wanted with me.”

Sometimes a survivor would ramble on for a long time, giving a completely disjointed account of what happened. Then survivors would collapse in tears, and women sitting next to them would gather around and comfort them.

One time I remember a young boy telling the most horrific story of how his mother was beheaded, and he didn’t shed a tear. Jean whispered to me that tears would come with the healing of his trauma. His experiences were still too raw and undigested. Later, Jean told me that survivors who had jumped from one experience to another in their telling, would gradually develop a narrative about their lives, locating the genocide within a larger context of purpose that would enable them to move forward in life.

Finding Purpose

These testimony meetings were only one element of a larger experience for survivors. Solace Ministries took a very holistic approach — helping survivors with food and housing, assisting with the educational needs of children and, more generally, becoming the extended family that survivors had lost in the genocide.

Orphans found surrogate parents and grandparents; widows found new purpose in life caring for orphans. And this was done within the larger framework of a loving community that believed in the possibility of new life.

Jean Gakwandi told me that when he first meets survivors, their identity is totally wrapped up in their problems — that is how they see themselves. The point of sharing their trauma with a community is that it helps release the revolving thoughts of revenge, anger and repetitious memories so that survivors can live in the present. And, maybe at some future point they may experience the beneficial catharsis of forgiving the perpetrator, although doing this prior to significant healing often results in emotional blunting — the inability to feel, love and play, because the wound has been covered over prematurely without processing the trauma.

Nurturing Community

In interviewing members of the Solace, they frequently described how they had become human again through the nurture of this healing community. Psychotherapy has its benefits — although it is often not possible in the face of mass disasters. This is where religious communities can play an important role — being a place where tears can freely flow; where a person can find an extended family of nurture and care; where in a holistic way life can be put back together.

However, would it not be even better, at least in the case of genocide, if Churches were prophetic, and challenge the hate and racism that gives rise to violence?

Click here to read the article on tuimotu.org.

Republished with permission: Tui Motu Magazine. Issue 245 February 2020: 6-7

Photos by Jerry Berndt. See more photos in Orphans of Rwanda Genocide

Donald E. Miller is the co-founder of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.