When CRCC’s “Spiritual Exemplars Project” team was invited to present about “resilience,” it was easy to think of many examples within our sample of 100+ spiritually engaged humanitarians who had endured and rebuilt after disaster strikes. Indeed, the majority of spiritual exemplars utilize faith to undergird a gritty perseverance and hopeful perspective, which allows them to stay on the front lines of many of the world’s most intractable problems.

At the same time, inspired by a subset of our exemplars, we wanted to show another side of resilience, one that problematizes the idea that exemplars must be martyrs or saviors to their causes and displays a little acknowledged value of spiritual sustenance: the prophetic call to end human suffering.

This subset — maybe 10 to 15 percent of our sample — embodies a perspective that I tentatively call “holistic resilience,” uniting resilience work with social justice activism by going beyond approaches that focus only on individual coping with vulnerability. Instead, these exemplars operate using an orientation to resilience which seeks to challenge the structures that create adversity in the first place.

Such exemplars ask, as resilience researcher Dorothy Bottrell does, “To what extent will adversity be tolerated, on the assumption that resilient individuals can and do cope? How much adversity should resilient individuals endure before social arrangements rather than individuals are targeted for intervention?” (From “Understanding ‘Marginal’ Perspectives: Toward a Social Theory of Resilience.” Qualitative Social Work. Research & Practice 8 (2009): 321-339.)

The little we know about faith and its ties to resilience focuses on faith’s ability to help people persevere, bounce back and find meaning in suffering. By focusing on some examples of holistic resilience, we get to see another side to the way faith fuels individuals through difficulty, one that highlights human flourishing in the face of trauma. Below you’ll find four examples from our sample of 104 spiritually engaged humanitarians. After briefly describing each of their relationships with resilience, I’ll conclude with three principles that others in the nonprofit, humanitarian and philanthropic spaces could benefit from.

Patrisse Cullors

Patrisse Cullors, one of three co-founders of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, is an archetypal model of this perspective on resilience. In my profile of her, I describe how Cullor’s vision and deep connection to her faith can be seen in the spirituality that sustains and inspires BLM and the other organizations she has founded. “The fight to save your life is a spiritual fight,” she says of working with people directly impacted by state violence and heavy policing.

But Cullors also believes that not all spiritualities support one’s resilience. As she told me, many spiritual traditions, in fact, further subjugate people. The organizations she founded, therefore, intentionally work to disrupt “martyr mentality,” in which people burn out mentally and physically in their attempts to serve others. They do so by using a mix of spiritual tools, often outside their traditional contexts, and by entrusting leadership to people shunned by traditional faith (the formerly incarcerated, sex workers, lgbtq identifying individuals, women).

This orientation has enabled the creation of a big tent where many religious orientations and faith beliefs, including the lack of belief, can co-exist in the fight against police violence and anti-black racism, while working to empower some of the most directly impacted communities recovering from contemporary and historic incidents of state violence.

Sr. Mary Scullion

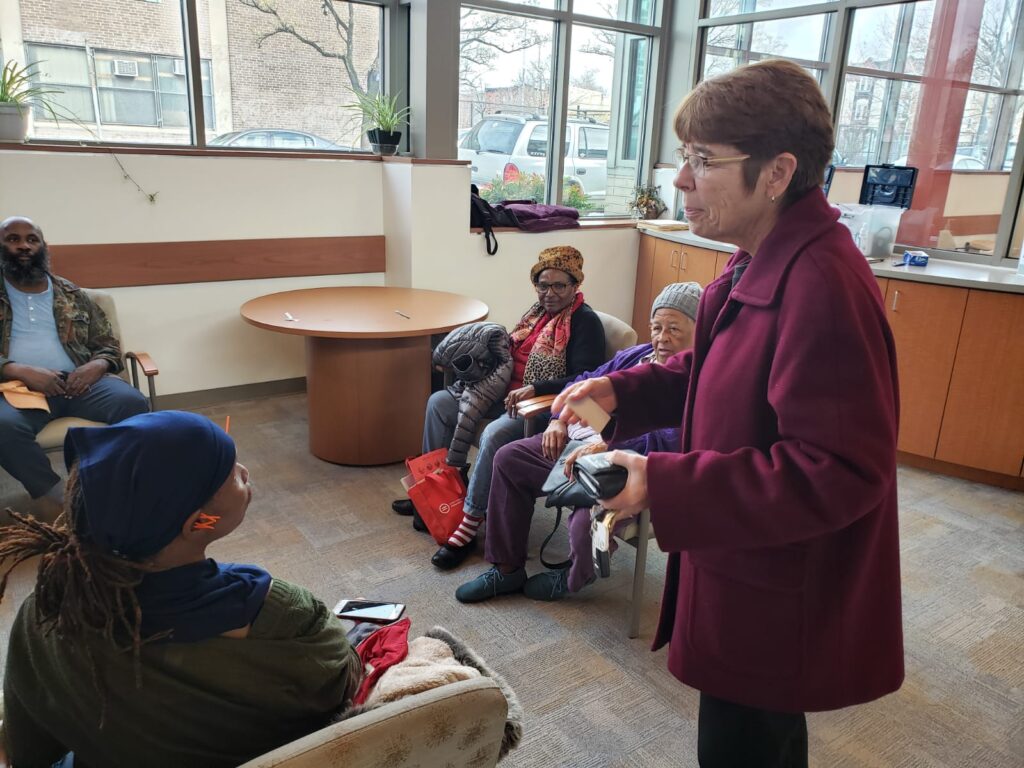

A consecrated Catholic sister, Mary Scullion heads Philadelphia’s Project HOME, one of the most prominent anti-homelessness organizations in the United States. Chris Herlinger profiled her for Global Sisters Report. Scullion believes that those who are experiencing homelessness are her real teachers, saying that they are “a prophetic presence” calling American society to a radical transformation of values and spirituality.

“In the Project Home community, we’ve always understood that homelessness is the canary in the mine,” she emphasizes. “It’s the prophetic call to all of us that there’s something radically wrong in our society that anybody is living on our streets.”

For Scullion, it’s not enough to pray or serve — she wants to solve.

Scullion also believes that her faith remains alive not just in service, but also in pursuit of reform within her own faith, to ensure equity and equality for all. For Sr. Scullion, that focus remains on women being allowed authority and leadership in the Catholic Church. As she puts it, “[T]he institutional structure of the Church needs radical transformation…. The role of women in the Church is an example of historical discrimination, and if the Church is going to survive, it’s going to have to change.” She goes on to quote Saul Alinsky saying that sisters must lead that change themselves, lest they be complicit in their own second-class citizenship. “Our faith has to be alive, and transformative,” she argues.

Sr. Scullion’s orientation to her faith and her commitment to those suffering homelessness provide proof that even in highly institutional environments, a holistic orientation to resilience can flourish — grounded in a commitment to correcting harms wherever you see them, even in your own institution.

Emily Saunders

Emily Saunders is a volunteer with Ajo Samaritans and No More Deaths, which leaves gallons of water and easy-open-cans of beans in the desert in an effort to reduce the number of migrants and asylum seekers who die on their journey crossing the US-Mexico border. As of May 2020, Saunders had participated in the recoveries of 23 migrants’ bodies in the desert.

The Spiritual Edge episode about her and her then-partner Scott Warren describes how their spirituality inspires them, despite their not identifying with an organized religion. Reported by Jude Joffe-Block, it tells the story of how Warren was acquitted of felony charges for aiding refugees after using a religious freedom defense. Another interesting aspect of her story reveals her grappling with what “resilience” looks like.

“Pain can carry us through to post-traumatic growth, resilience and aliveness,” Saunders, a licensed clinical social worker, says. “But then there’s a lot of unnecessary suffering in this world, fueled by hatred and greed and I think acting to alleviate that is skillful.”

Saunders has learned to trust directly-impacted populations and their ability to heal in their own way, learning from the communities she is serving. In many ways, she feels rescued by the migrants she has helped to survive the desert.

“As a teacher and a therapist, I am holding a witnessing presence for people who are also doing healing work within themselves and within their lineages. Here, healing violence that was created by border infrastructures and state violence…it’s not just on the landscape, it’s also in my body now too. In our bodies. And I don’t think I can talk about that with us without also talking about resilience, which is the inherent wisdom of people to heal ourselves.”

She calls this healing personal and collective, a reconnecting and transformational process that allows you to see the hope in communal experience. This is a perspective she believes she was gifted from the people she works with, citing a poem from Luis Valdez:

“tú eres mi otro,” you are my other me;

“si te hago daño, daño a mi,” if I harm you, I harm myself;

“si te respeto y te amo, me respeto y me amo a mi,” if I love and respect you, I love and respect myself.

Rachel Sumekh

Rachel Sumekh, one of our project’s three under 30 exemplars and founder of Swipe Out Hunger, exemplifies how young spiritually-motivated leaders have infused a holistic understanding of resilience into their worldview.

The daughter of two Jewish Iranian immigrants, Sumekh has many achievements, as I note in my profile of her. What I found most interesting about her is her leadership style, which embraces diversity, empowers young adults and incorporates self-care/spirituality in their advocacy.

Her model is attractive to the young people in that it empowers them while being highly replicable and centered on solving big problems. She has taken the scope of her organization from enabling college students to help feed their classmates, to addressing hunger on campuses nationwide, to trying to solve the higher education affordability crisis. Sumekh also feels it is her mission to make her faith more equitable, both in how it treats people of color within the community, and how it engages in issues of relevance outside the community, creating a platform focused on Jewish voices of color for change.

Finally, Sumekh is a strong advocate for cultural reform in her immigrant community. A staunch feminist, she refuses to be bullied into conforming to mores about her appearance or her choice to delay marriage. Instead, she embraces a strong vision of femininity inspired by Jewish lore, with hopes of interrupting the process of passing on harmful notions that may have infiltrated her religious practice. In the process, she also shrugs off an adherence to what she calls “a model minority mentality,” or the need for unachievable perfectionism.

“They (older generations) act with a model minority mentality because they think it’s still survival. Now my whole thing is, take a deep breath. We’ve made it, and now the question is not, how do we survive, but how do we thrive?”

Sumekh represents a dual consciousness of wanting to operate within systems while working to make them less harmful — from government, to big business, to higher ed to her faith communities. She sees all these spheres as connected to our collective well-being.

Common Principles in Holistic Resilience Approaches

Resilience researchers have noted that attempts to build resilience often hold individuals responsible for the barriers that they face, and maintain rather than challenge the inequitable structures of society.

As these brief snippets illustrate, spiritual exemplars who embody a holistically resilient perspective shed light on how resilient individuals can work to create impactful humanitarian organizations that support the resilience of others, using faith-based tools and insights, while fostering opportunities for systemic inequality to be challenged. They share principles that those in humanitarian, nonprofit and philanthropic spaces might learn from:

- Listen to those directly impacted by the problem you are trying to solve. In order to address the issue that caused the crisis in the first place, it is important to see directly impacted communities as authoritative sources of information about their own experience.

- Resilience is not resignation, and often requires an element of revolution. Holistic resilience approaches often involve questioning systems of authority or tradition in order to create solutions to problems and/or to provide tools for coping, recovery and support.

- Caring for oneself and one’s communities is an act of resilience. Exemplars of holistic resilience prioritize wellness in their lives and the lives of the communities they work with.

While work toward systemic change can be draining and often requires reservoirs of spiritual sustenance, that work can also be generative, in the right conditions. For these spiritually engaged humanitarians, the work of alleviating human suffering itself can often be a source of spiritual renewal.

As Grace Lee Boggs, famed civil rights activist, says in her work, Living for Change, “To make a revolution, people must not only struggle against existing institutions. They must make a philosophical/ spiritual leap and become more ‘human’ human beings. In order to change/transform the world, they must change/transform themselves.”

The work of holistically resilient spiritual exemplars shows that it is possible to give equal and simultaneous attention to individuals, communities and the wider systems in which they are embedded, striving for a model of resilience that is not simply persisting but also flourishing.

Hebah Farrag was the assistant director of research of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture through 2023.