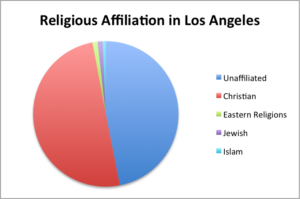

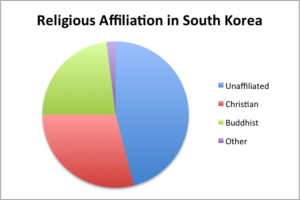

Looking at a simple pie chart depicting current patterns of affiliation in Los Angeles and Seoul—the comparison case in CRCC’s Religious Competition and Creative Innovation (RCCI) project—the cities seem remarkably similar.

About half of the adult population in Los Angeles identifies with some established religious institution, which makes L.A. more traditionally religious than other big coastal cities like New York City or San Francisco, but much less religious than Middle American metropolises such as Chicago, Dallas or Atlanta. (Source for pie chart.)

About half of the adult population in Los Angeles identifies with some established religious institution, which makes L.A. more traditionally religious than other big coastal cities like New York City or San Francisco, but much less religious than Middle American metropolises such as Chicago, Dallas or Atlanta. (Source for pie chart.)

South Korea’s adult population (which resembles Seoul’s population) is also divided about evenly between “nones” and people who adhere to some conventional form of religious practice or belief. But that’s where the comparison with L.A. becomes more complicated—and interesting. (Source for pie chart.)

South Korea’s adult population (which resembles Seoul’s population) is also divided about evenly between “nones” and people who adhere to some conventional form of religious practice or belief. But that’s where the comparison with L.A. becomes more complicated—and interesting. (Source for pie chart.)

Seil Oh, a research associate on the RCCI project and professor at Sogang University in Seoul, is currently studying the unaffiliated in Seoul. Oh’s dissertation research at Boston College also focused on some of the trends that were becoming apparent among American “nones” in the Northeast a decade ago.

“There were already many unchurched believers,” said Oh, pointing to a phenomenon that makes “nones” in the U.S. different from their counterparts in South Korea, where disaffiliated adults tend to express no interest in any kind of spiritual belief. “In America the discourses around spirituality versus religiosity have been driving efforts to explain the beliefs and behaviors of unchurched believers.”

Why are “nones” in the U.S. typically more interested in non-institutional forms of spirituality like yoga, meditation and energy healing than their counterparts in South Korea? The influence of war and authoritarianism on Korean culture as well as the interplay between Protestantism and capitalism in Korea’s post-war economic development are all key factors in that very complex equation.

After the end of open warfare on the Korean Peninsula in 1953, nominally democratic South Korea suffered through a series of coups and authoritarian regimes until the 1980s. During those decades of instability, the South also experienced an influx of capital from the U.S., along with waves of Protestant missionaries who dramatically increased the religiosity of a populace that had been largely indifferent to its ancient Buddhist culture and small Christian minorities before the war. But during the country’s rapid industrialization all of that changed.

“Workers left rural areas for Seoul to earn money,” said Oh. “Whether they had their own religion or not, they became Protestant to get support from the local church.”

Then, in the pivotal year of 1987, a student leader of Seoul National University’s pro-democracy movement died during a brutal interrogation at the hands of government security personnel. The student’s death became the rallying point for millions of protestors around the country who compelled the ruling party to allow for the direct election of the country’s president.

The heyday of South Korea Protestantism occurred between the advent of full democracy in 1987 and the turn of the millennium. Megachurches like Yoido Full Gospel flourished, and the percentage of disaffiliated adults dropped from about 90 percent at the end of the Korean War to 50 percent.

While it might seem that religious affiliation rates in Los Angeles and Seoul are heading in opposite directions, Christianity may have reached its saturation point in Korean culture. The entanglement of Protestantism and capitalism in South Korea has proved to be a poor bargain for Protestant Christianity: At start of the 2000s, stories of corruption began to taint the reputations of many Korean megachurches, including Yoido, and the appeal of the faith began to diminish for the country’s millennials.

“In American culture,” Oh said, “youth don’t go to church, but they’re still spiritual. The majority of South Korean youth are not interested in spiritual life at all. They’re more interested in material life, secular life.”

A photo posted by USC Religion & Civic Culture (@usccrcc) on

Oh sees that difference as a consequence, in part, of the deep history of civil religion in the United States—a country wrested from its indigenous inhabitants by ardent colonial religionists and founded on the notion that citizens could believe whatever they want, as long as they believed in something. Without a similar interweaving of national and religious identities, South Korea has instead made a civil religion of the free-market capitalism that defined its identity during the Cold War.

Still, even if the current cohort of South Korean “nones” lacks the impulse toward spiritual seeking that defines their counterparts in the U.S., Oh believes their children will begin to look for deeper existential meaning than the latest K-Pop tune or digital gadget can provide.

“I feel like it will be the next generation that rediscovers religion,” he said. “Should I be happier? That will be the next conundrum for Korean youth.”

Korean youth culture seems vibrant on the surface—Seoul’s abundant and affordable cafés, restaurants and clubs are filled with young people, and the quirky exuberance of K-pop influences fashion and advertising as well as music. But South Korea also has one of the highest suicide rates in the world. The crisis that prompts a turn toward religiosity may not be in Seoul’s future—it may be happening right now.

Nick Street was a senior writer with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.