When Roanoke, Virginia Mayor David Bowers referred to the internment of the Japanese Americans in the context of the terrorist attacks by ISIS, he wasn’t the first to see the parallels between World War II and today. Japanese and Muslim American community leaders also have recognized that the fear of Muslims following terrorist attacks reflects the fear of Japanese following Pearl Harbor.

https://twitter.com/WesleyLowery/status/667076027198361601/photo/1

Bowers has since apologized for evoking the internment, but not for requesting that government and non-profit agencies suspend assistance to Syrian refugees.

“You would think that the common framework today would be thinking of how that should never happen again,” Traci Ishigo, program coordinator at the Japanese American Citizens League, Pacific Southwest District. “It just goes to show the education that’s needed.”

Following 9/11, JACL and other groups reached out to the Council of American-Islamic Relations to show their support. CAIR-LA has attended remembrance day ceremonies for the internment as well.

It’s not only mass internment that these two communities fear. “There were search and seizures of individuals, and we saw a lot of folks deported after 9/11, and so that concept of displacing people and detaining them was still a reality,” Ishigo said.

The general mistrust of Muslims, including both refugees and American citizens, also reflects the hostility toward Japanese Americans before and during World War II. Since the Paris attacks on November 13, CAIR has received more reports of Islamophobic threats and actions than any other limited time since 9/11.

JACL and CAIR started a program in 2007 that educates Japanese American and Muslim American young people on their ethnic identities and civil rights activism. The lessons of the Bridging Communities program hits home when the group visits Manzanar, the site of an internment camp four hours north of Los Angeles.

[RoyalSlider Error] Incorrect RoyalSlider ID or problem with query.

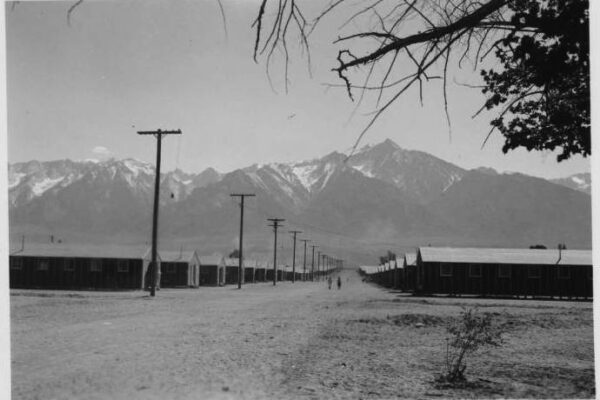

The International Missionary Photography Archive serves to capture some images of what life was like in the internment camps, as Maryknoll Catholic priests ministered to the internees. The sisters pictured were internees themselves.

A flat field with the Sierra Mountains rising dramatically behind it, today Manzanar is a memorial and museum with few remnants of the 504 barracks that housed more than 10,000 people from 1942-1945.

The government moved Japanese citizens and non-citizens to 10 camps with no more than they could carry. They had to sell or abandon their property or leave it in the hands of neighbors or religious groups.

Living conditions were difficult in the desolate camps. Manzanar’s desert location meant extremely hot summers and cold winters, and the supplies and food were poor.

Jon Miller, senior research associate and director of IMPA, says these photos reflect that “a sustained effort went into the creation of an aura of ‘normalcy’ in the camp.”

He recently visited Manzanar and pulled the above photos from the archive. You can find more photos of other internment camps on the USC Digital Library.

In one of the video displays at the museum, Miller told us, an elderly woman survivor expresses her fear that what she lived through could happen again to Muslim Americans.

By passing the stories of the internment on to the next generation, the Bridging Communities program hopes to build a base of young people who are watching the government’s actions and speaking up for each other.

“We’re hoping for them to come out of this program feeling as though they’ve grown in their own feelings of self, and also in terms of their outlook in this world and how they can be agents of social change wherever they go,” Ishigo said.

Megan Sweas is the editor and director of communications with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.