This article originally appeared in BOOM: A Journal of California.

Mt. Hollywood Congregational Church was in trouble. Its congregation had become too small to sustain the decaying Los Feliz building that had once been the spiritual home for a community of about 300 people. Its pastor had resigned in poor health.

So it fell to Jim Burklo, chair of the church’s building committee, to state the obvious to the remaining seventy-five or so members: “We got no pastor. We’ve got a building that’s a wreck. And there’s no money.”

Burklo said later of his fellow congregants: “These are all teachers and actors and musicians. You know, these people don’t have any money. There were maybe three people in the whole group who could cough up more than a standard pledge. So it’s like, forget it.”

So in 2011, the congregation decided to sell its building, a century-old outpost of a rapidly declining Protestant denomination, and rent space from a nearby Lutheran church that was also becoming a shadow of its former self. For some, a minority of members, Mt. Hollywood’s identity was inseparable from its historic home, and they chose to leave the fold rather than move into the Lutherans’ renovated Sunday School space.

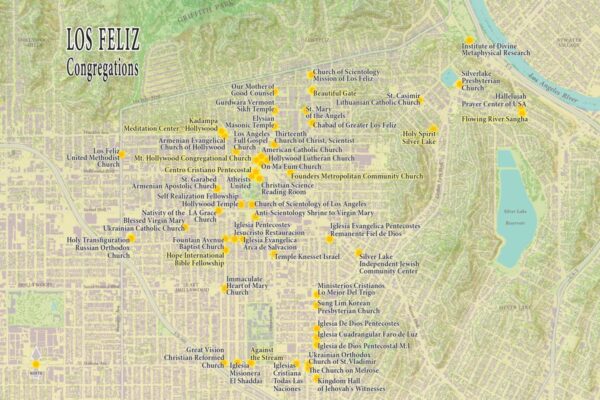

Explore an interactive map of religious congregations in Los Feliz

Burklo cast Mt. Hollywood’s transition in a positive light. “Some of the people who quit were kind of very traditional,” he said. “I think the most important aspect of this transition has been that we did not wait until we completely evaporated before we decided to make the change.” The congregants who remained, he said, “were loose, free-spirited characters who were like, this is great. It was like a millstone dropped off the neck. Let’s focus on our community and not on the churchy stuff. The whole group just felt light.”

Mt. Hollywood’s willingness to divest itself of some of its institutional trappings—in addition to selling its physical plant, the church dropped many elements of its formal liturgy—was a prerequisite for Anne Cohen, who accepted a call as minister to Mt. Hollywood a few months after the congregation made its move.

“If they had not sold the building I would not have applied for the job,” Cohen said. “They had such an amazing reputation of being world-changers and community service people, and they couldn’t do it anymore, because that building was a mess and they didn’t have the money to fix it. I didn’t want to serve a church where maintenance was the main issue.”

At first glance, Mt. Hollywood’s story seems to affirm the broader narrative that dominates news about religious affiliation in the United States. We’re living in a time of great religious flux. Nearly a third of young adults in the United States have left organized religion altogether. Survey data from Pew and other national polling organizations show that mainline Protestants are losing the numbers game, and that most of those who are still drawn to established communities are far less attached to traditional institutions than were their parents and grandparents.1 Many traditional institutions—particularly mainline Protestant denominations like the Lutherans and Congregationalists—are edging toward extinction.

Still, the news of religion’s imminent demise is more than a little premature. Our research on religious innovation and change in Southern California suggests that understanding how Mt. Hollywood and other diverse congregations fit into the vibrant religious ecology of their neighborhoods yields a far more complex—and dynamic—picture of the potential future of American religion than those reports suggest.

“We were doing a food pantry with them every week here on this site,” said Reverend Dr. Neil Cazares-Thomas as he stood in the basement of the building that had formerly housed Mt. Hollywood Congregational Church. Over the buzz of saws and the thump of hammers, he said, “They contacted me just before Christmas and said look, you know, we’re in decline. We can’t afford the building. Would you be interested in buying it from us? And I thought for two seconds and said absolutely.”

Cazares-Thomas’s congregation, Founders Metropolitan Community Church, had outgrown its facility in West Hollywood and purchased a former Methodist church in Los Feliz in 2008. Five years later, Founders MCC—a “radically inclusive” Protestant denomination founded in the late 1960s by a gay, former Pentecostal pastor—was already bursting at the seams of its new home. Mt. Hollywood’s church, about a mile away, was just the right fit. “We’re now averaging about 300 folks over three services on a Sunday,” said Cazares-Thomas.

Founders MCC’s former home was in turn bought by the Kadampa Meditation Center-Hollywood in 2013. KMC-Hollywood, one of eight Kadampa centers in California, has become a sort of neighborhood Buddhist temple, typically attracting forty to fifty people to the classes and guided meditations they offer most days of the week, according to resident teacher Gen Kelsang Rigpa.

“It’s really local,” Rigpa said. “I would say literally 95 percent of the people that come here say the same thing: ‘I’ve been driving by this place for a year. I’ve seen it, I live around the corner, I just wanted to check it out.'”

In Los Feliz, in neighboring Silver Lake, and across the rest of Southern California, our research team—two sociologists, an anthropologist, and a journalist—found a dramatic proliferation in the number of choices available to those who are looking for both spiritual practice and community. To our surprise, we did not come across many religious mashups—few Muslafarians or Buddangelicals in the mix—though we have come across a few. But if you want a self-help take on Tibetan meditation, a godless recovery group, gay-friendly Catholic mass, hipster Bible study, socially conscious evangelicalism, or freeform mainline Protestantism, you are living in the right era. Far from being vitiated by the overall religious disaffiliation trend evident in the United States, religion in Southern California is being revitalized by it, as religious “nones” create new forms of purposeful community and spark innovation among groups that may have never before experimented with rituals, worship styles, or modes of organization.

Indeed, in our research, we are not finding a spiritual wasteland but, rather, a wild, wild West of religion.

Los Feliz is a small neighborhood—about two square miles, bounded by the Los Angeles River, Griffith Park, and Western Avenue to the east, north, and west. The neighborhood’s southern boundary is subject to some debate. Depending on whom you ask, Los Feliz is a rectangle completed by Sunset or Santa Monica Boulevard, or an inverted triangle with its bottom angle composed of the intersection of Heliotrope and Melrose (known to the local hipsters as “Hel-Mel”).

More than 40 percent of its roughly 40,000 residents are foreign born—an unusually high statistic, even by Los Angeles standards. Among the diverse array of immigrant groups, the most common countries of origin are Armenia (21 percent) and Mexico (10 percent). At $50,000 a year, the average household income in Los Feliz is in the middle of the bell curve for Los Angeles County, but that unremarkable number belies a very atypical range of incomes in such a small area. Tony hillside mansions between Los Feliz Boulevard and Griffith Park attract A-list actors, rock stars, and movie producers. Dense, pedestrian- and transit-friendly areas along Vermont and Hillhurst are popular with young creative types. The “flats” below Sunset are much poorer and denser than areas farther north.

This dramatically varied cultural and socioeconomic mix makes Los Feliz a microcosm of the diversity of Greater Los Angeles. Within the neighborhood’s two square miles, there are no fewer than fifty religious groups, including Catholics, Mormons, Pentecostals, Buddhists, Jews, Self-Realization Fellowship, the Church of Scientology, and Atheists United, which although it is irreligious, functions as a type of “church” of unbelief. Los Feliz’s eclecticism is also remarkably dynamic. Gentrification is rapidly reshaping its cultural landscape, along with its religious ecosystem.

Los Feliz and neighboring Silver Lake combine to form one of the “coolest” areas in Los Angeles, putting it in the running for one of the coolest places on Earth. How do you measure cool? In 2012, Forbes magazine analyzed neighborhood data such as walkability scores, the prevalence of coffee shops, the percentage of residents who work in artistic occupations, and access to food trucks. Once the numbers were crunched, they named Silver Lake as the “Best Hipster Neighborhood” in the United States. The writers at Forbes are not the only ones measuring cool. In late 2013, the Los Angeles County real estate website PropertyShark.com crowned Los Feliz as LA’s “Most Rapidly-Gentrifying Neighborhood.”

Whether it is called urban renewal or gentrification, the process is fairly straightforward. Artists, recent college grads, yuppies, and empty-nesters—largely but not exclusively white—move into strategically situated urban neighborhoods like Los Feliz. The new arrivals open coffee shops and restaurants, renovate their homes, and attract improved city services, all of which increase the demand for housing and cause home prices and rents to spike.

Although gentrification in and around Los Feliz has had a predictable impact on the cost of housing, the impact on religious congregations is not as clear. Some congregations have been immune to the demographic shifts. At first glance, Centro Cristiano Pentecostal seems vulnerable to the exodus of working-class Latino residents from the area. The Spanish-speaking Pentecostal church sits only a few blocks from vintage clothing stores and bars offering “hand-crafted” cocktails on Vermont Avenue, but it isn’t going anywhere. Its three weekend services followed by potluck meals served in the parking lot draw over 400 worshippers, and the building buzzes with activity nearly every day of the week.

The Centro Cristiano Pentecostal owns its building, so the congregation’s operating budget doesn’t need to rise to keep pace with climbing rental prices. As the surrounding neighborhood has changed, fewer members walk or take the bus to church than in the past, but the church offers a sense of belonging and a traditional Pentecostal worship service that is hard to duplicate. Membership has remained steady because congregants are willing to drive from all over the city for the vibrant and intense experience of its Pentecostal service.

Other congregations have recently opened in Los Feliz to cater to the spiritual needs of the creative class that has flocked to the area. Pastors Sam and Priya Theophylus emigrated from India as church planters and were drawn to the neighborhood because, as Pastor Sam says in a video posted on their church’s website, “Los Feliz is a neighborhood that creates. . . people are such seekers here.”2

Their church, the Beautiful Gate, occupies a rented space above a clothing boutique. Pastors Sam and Priya lead weekly services that they have specifically tailored to new and emerging sensibilities in this rapidly changing neighborhood.

Not all religious groups are equally equipped to weather the gentrification process. Pastor Ed Carey built his congregation, Hope International Bible Fellowship, by ministering to the down-and-out living on the area’s grittiest streets. Twice a day the fellowship serves hot meals to local homeless and working poor people, and the church has graduated hundreds of people from its residential, substance-abuse recovery program. The transformation of Los Feliz over the past decade or so has both dramatically decreased the number of local residents in need of a free meal, and increased the number of neighbor complaints about the small crowds that assemble outside the church during mealtimes. Passing by a new, stylish restaurant offering “organic, local, and small-farm produce” Carey recalled that, ten years ago, “People were scared to come here. Now on Sunday mornings they line up all the way down the block waiting in line for brunch.” There was no sarcasm or animosity in Carey’s voice, but, gazing philosophically at the sharply dressed lunch crowd, he asked, “I wonder if our congregation will gentrify, too?”

Founders Metropolitan Community Church is the flagship congregation of the Metropolitan Community Church movement, which was established in 1968 by Rev. Troy Perry. Historically, Founders MCC—and the MCC movement—has served the spiritual needs of the LGBT community, though more recently the church has been attracting straight members who are drawn to its nonjudgmental approach to religion. The church describes itself as “radically inclusive,” which most obviously relates to sexual identity (LGBT and straight), but also encompasses the wide range of spiritual needs and beliefs that people bring through the church door. In addition to telegraphing its openness to an unusually wide range of identities, the phrase “come as you are” at Founders MCC also means that worshipers are invited to shape their own beliefs about what or who God is, and about how “s/he” operates in the universe as well as in their individual lives.

Lisa Arnold, who has been attending Founders MCC for several years said, “I had heard about it and I knew it was a gay church. I didn’t know the history of it, about Reverend Troy. I’ve learned all of that since I’ve been here. But the one thing that I felt was love, acceptance, and worthiness. The fact that you can walk into a place that fully accepts you. . . really is just such a blessing.”

Most of Founders MCC’s members are middle-aged or older, although there are a handful of younger people in the congregation. Its cultural and ethnic mix is remarkably diverse for a Protestant congregation, and the crowds at Sunday services are about evenly divided between solo attendees and couples. Just like many predominantly straight churches, Founders MCC has a big focus on “family.” This emphasis is a part of a broader push to create a deeper sense of community for members, many of whom—both gay and straight—are parents of young children. PJ Escobar, who is originally from Texas and who spends almost all of his free time volunteering at the church, said that when he first came to the church, he realized he had found a home. “I knew that I finally belonged somewhere,” Escobar said. “These people here are my family.”

This keen focus on the cultivation of a sense of belonging points toward one of the most remarkable characteristics of Founders MCC, which is in some respects a “mini-megachurch.” Even though each of the three Sunday services draws no more than 100 people, the church operates as a community center of sorts for Los Feliz. Over the course of any given week, several different community organizations, spiritual and Bible study groups, twelve-step groups, and a pre-school use the church’s meeting spaces. Founders MCC has also nurtured relationships with other churches and organizations in the community, collaborating, for example, with Holy Spirit Silver Lake and a nearby Mormon church on different service-oriented projects. These different groups and activities mean that about a thousand people pass through Founders MCC during a typical week, giving the relatively modest church an outsize cultural footprint in the community.

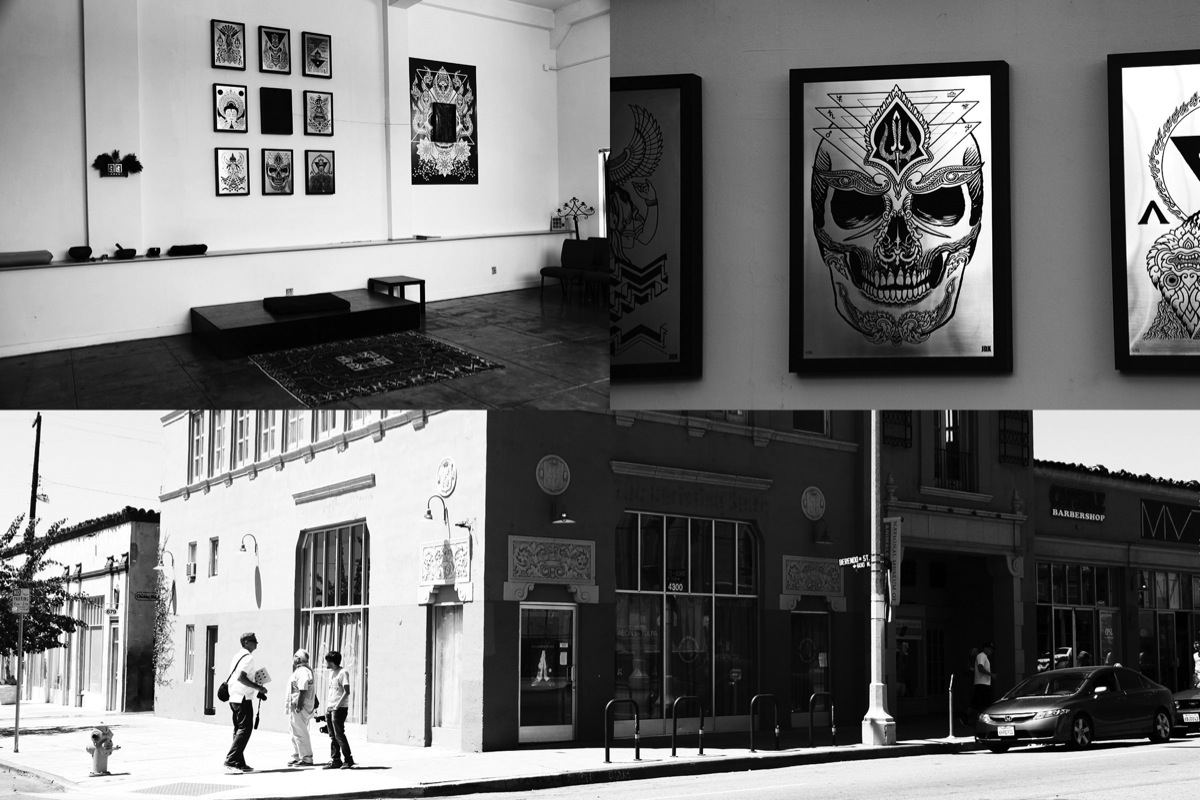

Located in a loft-like gallery space above Barella’s Bar and Kitchen on Hyperion Avenue, Holy Spirit Silver Lake is a small, “off the books” experimental congregation. Holy Spirit started as a home Bible-study group that has evolved into a small congregation with twenty to twenty-five people attending services on Thursday evenings. Randy Kimmler, one of the organizers, at whose home the first Bible studies were held, said that Holy Spirit grew organically from the group’s first meeting during Lent in 2005.

“We said, let’s just go ahead and meet weekly for Eucharist together in the middle of the week,” Kimmler recalled. “So we did that for like, I guess for a year. No one was invited in or anything, it was just, you know, done.”

Attendees include a core of regular participants, and a revolving group of others. The membership of the church is directly tied to the LA Episcopal Diocese. Several of the leaders and organizers, as well as other semiregular participants, are employees of the diocese or are otherwise active in diocesan activities. Others, however, have no connection to the Episcopal church and are not otherwise drawn to Holy Spirit because of its Episcopal identity.

A number of local Episcopal priests also come to Holy Spirit on Thursdays to have their own time of worship and reflection. Often they want to try out elements of the homily they are preparing for the coming Sunday morning. Visiting priests also administer the Eucharist as a part of the Holy Spirit service.

Holy Spirit has organized its evening service into a triptych that they call “the Lord’s supper in three courses.” The first course allows participants to socialize with one another around food and drink. The second is a contemporary Eucharist service—where congregants stand in a circle and pass the bread, cup, and blessing to each other—and includes a time of reflection usually based on a piece of biblical scripture or other related material. The final course moves to more socializing over dessert.

Unless you knew that Holy Spirit is affiliated with the Episcopal Diocese, you probably wouldn’t recognize the church culture as Episcopalian. They have intentionally styled their community as a place for non-church types to gather for spiritual fellowship and to connect with one another around service projects. Toward that end, several members of Holy Spirit launched a program to provide laundry services once a month to homeless people and the working poor. Their initiative is part of a national nonprofit Laundry Love movement that many religious as well as nonreligious groups have joined over the last several years. Holy Spirit has partnered with Founders MCC in its local Laundry Love effort.3

“I’m really glad we started to do this,” said twenty-four-year-old Joey Courtney, who recently decided to enter the Episcopal priesthood. “It’s a little bit more action based, and I think that’s something I would definitely remember when I start in a church, is that action needs to be there and that people really respond well to it. And I think we’ve seen our numbers rise because of it.”

Under the name “Spirit Studio,” Holy Spirit sublets its rental space to support a variety of community-oriented activities, including a gallery for art showings, a twice-monthly writing workshop, a group that meets to write letters to prisoners, a Saturday morning yoga-for-beginners program, and a social gathering for local LGBT seniors. As with Founders MCC, Holy Spirit has a disproportionate impact in its community relative to its size.

Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk and founder of the Order of Interbeing, has said that “the next Buddha, the Buddha of the West, will come as the sangha.”4

For anyone paying attention to recent reports on the changing American religious landscape, which suggest that attendance at religious services has been declining for decades, Thich Nhat Hanh’s claim that the West will be the wellspring of sangha, the Sanskrit term for “spiritual community,” might seem woefully mistaken.

Yet that assumption overlooks one of the most important innovations that Buddhism in the West has produced over the past several decades through the proliferation of mindfulness practices: the emphasis on “taking refuge in community.” Although psychological therapy, self-help, and personal wellbeing figure into most discussions of mindfulness, mindfulness practitioners are also actively creating moral or spiritual communities that support their individual commitments to personal growth.

The Western idea of sangha is perhaps most enthusiastically embraced in cities such as Los Angeles, which is often characterized, somewhat unfairly, as the poster-child for fragmented urban landscapes marked by isolation and disconnection from community. Take for instance Joshua Kauffman, who helped organize and establish the Flowing River Sangha, a community practicing mindfulness in the Thich Nhat Hanh tradition in Silver Lake. Before he and his fellow sangha members started meeting in their current location in a yoga studio, Kauffman drove every Saturday morning across LA from his home in the Atwater Village area to meditate with a sangha in Culver City. Having to schlepp across LA might seem like as good a reason as any to lose one’s religion, but for Kauffman, who was supporting his recovery from a serious illness through regular mindfulness practice, it was a worthwhile commute.

“My evolution to sort of be more of a regular practitioner allowed me to move through the whole experience with a certain degree of grace,” Kauffman said. “I didn’t fight it. I didn’t struggle against it. I really focused on just being open to the experience instead of pushing against it. All of my practice during those years was really about figuring out how to, you know, to not resist and therefore to not suffer.”

Kauffman made the weekly journey for five years, interspersing his practice routine with visits to Deer Park Monastery, a Buddhist sanctuary and retreat center in rural San Diego County. At Deer Park, Kauffman met other devoted mindfulness practitioners who were also yearning for a sangha in northeast LA. Kauffman was already an ordained lay member of the Order of Interbeing—which meant that he knew the rituals, chants, and form of mindfulness practices—so the group began meeting regularly at a yoga studio in their neighborhood on Saturday mornings. Leadership now rotates among the regular practitioners, which means that the appointed person gets to choose a reading of his or her choice by their spiritual teacher, Thich Nhat Hanh (known informally as “Thay” to his followers).

Attracting about a dozen practitioners from northeast LA neighborhoods including Los Feliz, Flowing River Sangha is one of the many hyper-local mindfulness communities that are popping up around Los Angeles. Their proliferation is a sign not only that people are seeking meditative mindfulness practices to ease the anxiety, stress, and emptiness that can accompany life in twenty-first-century California, but also that people in an age of flux and disaffiliation are eager to find new forms of meaningful community. Noah Levine, the lead meditation teacher of Against the Stream, an LA-based Buddhist meditation society, regularly conveys this desire for a community of spiritual practitioners in Dharma talks he gives at the organization’s centers in Hollywood and Santa Monica:

This kind of spiritual practice, and really all kinds of spiritual practice, is very much solitary. Meditating by yourself, inside yourself, training your own mind.. . . But the Buddha was quite clear that his teaching, that this path was a relational path. Yes, we have to all meditate for ourselves. . . but he was insistent that we do it in groups, in community, that we do it in refuge, which means a place of shelter from some level of suffering, that we go take refuge in a community of people and that we do our individual work in a relational environment.

Speaking to an audience of about a hundred mindfulness practitioners who had come to hear him talk one evening, Levine emphasized the need for mindfulness practitioners to embed themselves within a community of other meditators, whom he referred to as “spiritual friends following the path.”

That search for a sense of self-transcendence, both through a commitment to some form of practice associated with the examined life and within a community of likeminded practitioners, is the foundation of any religious movement. For various reasons, many of the institutions that formed centuries or even millennia ago are no longer fulfilling the yearnings of the current generation of seekers. As we are finding in Los Feliz and elsewhere, that doesn’t mean that religion is dead—rather that, as in any other ecosystem, old growth must eventually die off to make room for new.

Notes

Photographs by Nick Street.

1 See, for example, the General Social Survey, conducted each year (with a few exceptions) since 1972. See also decennial Religious Congregations and Membership Study. Both the GSS and RCMS are available for analysis at thearda.com.

3 https://crcc.usc.edu/laundry-love/

Richard Flory is the executive director of the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

Nalika Gajaweera was a senior research analyst with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture through 2023.

Andrew Johnson is a contributing fellow with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

Nick Street was a senior writer with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.