Parveena Ahanger, a well-known Kashmiri activist, exuded her characteristic warmth as she sat cross-legged in the kitchen on a freezing January afternoon in Srinagar, the region’s largest city. The warmest corner of her modest home, the space was perfused with fragrant spices of the day’s cooking – a hearty meal of lentils, vegetables and meat – and the warm embrace of the Kangri, an earthen pot filled with burning embers to take the chill out of the air.

Raised in a traditional Kashmiri Muslim family with a “lot of loving care,” the dupatta-clad Ahanger metamorphosed from being caregiver to her family to being the “iron lady of Kashmir,” the day her teen son disappeared. The tragedy that has beset her life three decades ago hasn’t come to an end. But armed by her relentless faith in God and an innate sense of motherhood and care for others beyond her family, Ahanger soldiers on.

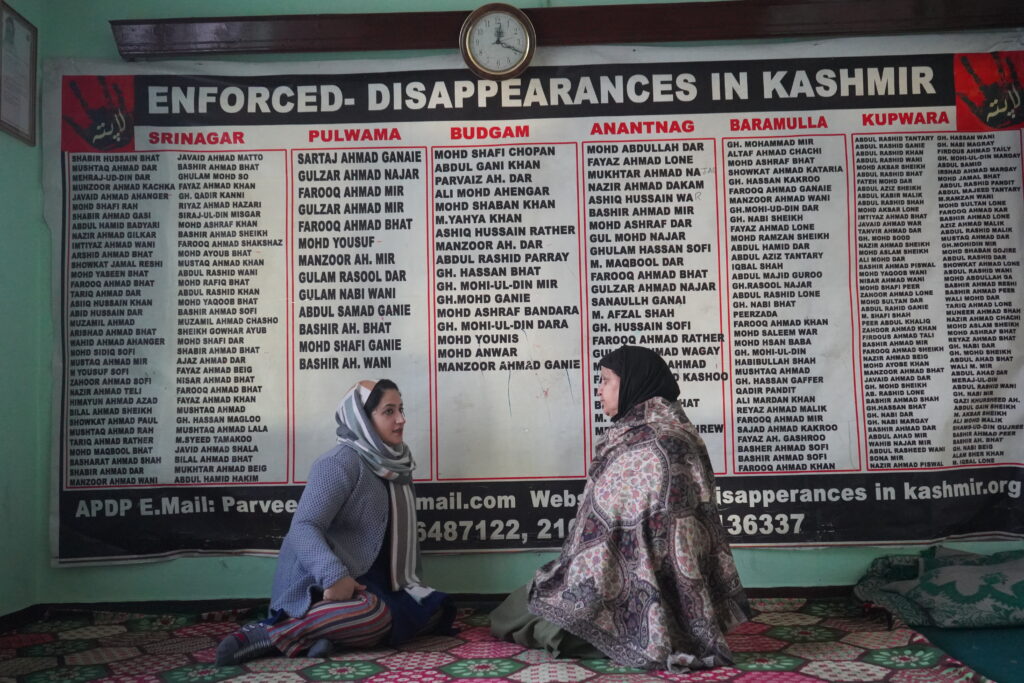

Ahanger, 63, is the chairperson of the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) and has been at the forefront of the cause for human rights in Jammu and Kashmir. In 2017, she was given the Rafto Prize and two years later, she was included in BBC 100 Women. These prizes recognized Ahanger as the voice of Kashmiri women grieving the enforced disappearances of their loved ones in one of the most restive parts of the world.

Kashmir, disputed between India and Pakistan, is home to a decades-long militancy that peaked in the 1990s. The militancy in Indian-administered Kashmir is known to be supported by Pakistan, which nurtures and harbors many militant groups on their territory. Indian security forces have also long been accused of human rights violations in the Kashmir valley, fueling further dissent among local Kashmiris and abetting pro-Pakistan insurgency in the region. While India often denies the abuses, at times it also justifies crackdowns as necessary counterterrorism measures.

In 1990, at the height of the Kashmir insurgency, Parveena’s son Javaid Ahmad Ahanger, a 16-year-old schoolboy, was picked up in a midnight raid. He was sleeping at his cousin’s house in the neighborhood, where he was studying for his examinations, when security officials whisked him away along with two other cousins. The cousins were let go. Javaid never returned.

Since that fateful morning, Ahanger has knocked on every door possible to get her boy back, including the highest court of the nation, to no avail. Many years ago, two detained militants told a judge that they had seen Javaid Ahanger at an interrogation center. Security officials never charged him of a crime, nor was he ever presented before the court. “They lied and said that my son had been released,” Ahanger says. It was Javaid’s namesake—Javaid Ahmad Bhat, a wanted militant –who the authorities were after, she claims.

In the years since Javaid’s disappearance, Ahanger’s mornings have not changed. She wakes up early for her prayers, recites the Quran, which she memorized as a young girl, and continues to fight – for her son and the numerous other sons, brothers and husbands that have been gone missing. Her search has been fueled by her faith.

“All I know is that nothing in this world happens without Allah’s wish. He is the one who has put me on trial, and He is the one who has provided me the strength to withstand everything that has come my way.”

-Parveena Ahanger

The eldest of her siblings, Ahanger attended school until grade six. She married young and would seldom leave the house. Javaid is her second-born, an obedient boy who struggled with his speech.

“When all of this started, I was very young and did not know the ways of this world,” Ahanger says. During her countless visits to police stations, detention centers, offices of politicians, she met numerous other women looking for their loved ones. In 1994, she set up the APDP to fight to unite them.

Ahanger traveled from village to village, gathering information on reported cases, helping families register police reports and file court cases. She braved through curfews and persisted despite bureaucratic hurdles and financial troubles, all while raising her three remaining children and caring for her ailing husband.

Her youngest, Saima, was only four when Javaid was taken away. “I used to cry so much that it started affecting my vision,” Ahanager says. “A pir baba [spiritual guide] once told me that I must stay alive for my daughter. My sons could endure hardships without me, but I needed to be there for my daughter.”

Today, Saima is a married woman herself, and helps her mother run the organization along with a trusted associate.

APDP is focused on various issues related to enforced disappearances, custodial torture, sexual assault, as well as medical and legal aid. It has organized peaceful protests and championed the cause of human rights in the conflict zone. Since 2007, the number of enforced disappearances in the region has sharply gone down, and much of that has to do with the awareness raised by Ahanger’s organization.

Yet, hardly a day goes by when she doesn’t meet a grieving family that hasn’t received closure. Her love for Javaid has transmuted into compassion for everyone.

“People keep coming to me with their woes, and I keep taking it upon myself to help them in every possible way I can,” she says. It is her path of love that takes her inside the hearts of people. “The bond between me and them is almost holy, they keep it close to them and it gives them strength.”

In August 2019, Kashmir went through a dramatic political shift, as the state’s special status was lifted, and it was turned into a territory of the central government, stripping it of its privileges. The aftermath of the subsequent and continuing crackdown in the region was felt, and continues to be felt not just by militants but also protestors, journalists and common citizens.

In October 2020, Ahanger had just finished reading the namaz – her daily prayers – when she was greeted by India’s counter-terrorism taskforce officers, also known as the NIA, at her doorstep. As part of multi-site raids on well-known NGOs and journalists operating in the Valley, Ahanger was questioned for hours, her documents and technology confiscated. While Ahanger’s organization emerged out of the raids, others, like the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society, or JKCCS, haven’t survived. Its founder, Khurram Parvez, has been incarcerated since November 2021 on charges of terror financing. For decades, both APDP and JKCSS were frontline defenders of human rights issues in the region.

Since the raids, APDP has remained largely dormant, its silent protests disappeared. Work continues in subdued and limited departments, like the distribution of medicines and ration to families of the aggrieved.

As she has aged from the young mother who lost her son, Ahanger has begun experiencing health issues herself. But she persists, insisting she must keep going for her son and the countless others whose families rely on her for support.

Ahanger believes her son Javaid is still alive, now a grown man, locked up somewhere. To the question about whether she hopes of having him back one day, she firmly responds: “I swear on Allah that I do.”

“There are two Eids in a year. It will be a third one for me when that happens,” she says.

Click here for more stories on engaged spirituality.

Soumya Shankar is a journalist fellow with the Spiritual Exemplars Project.