Civil unrest between communities of color and law enforcement officers was roiling Ferguson, Missouri in the fall of 2014.

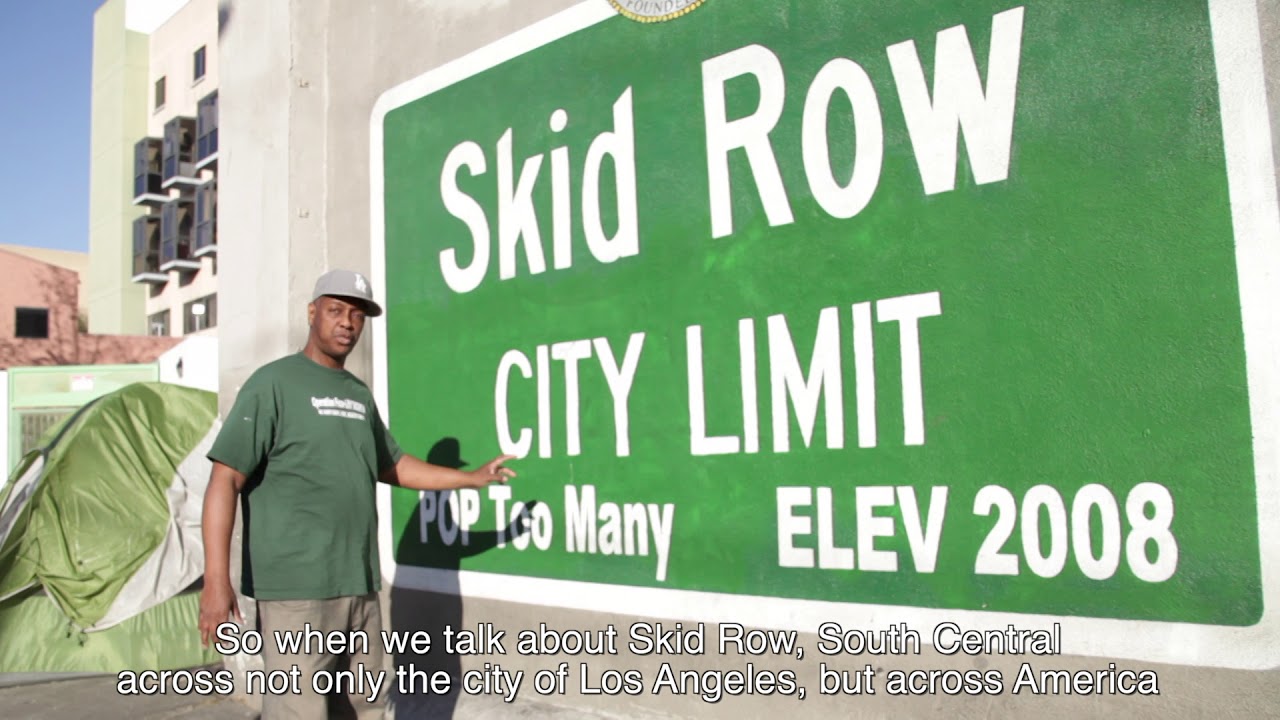

Tensions were also building in the Skid Row section of downtown Los Angeles. News of violence in Gaza, and the Israeli Defense Forces’ disproportionate response to it, was also making headlines.

At New City Church, near Skid Row, a young African-American minister took the stage to offer a prayer. The cavernous auditorium held roughly 300 people, a mix of Asians from nearby Koreatown, hipsters from recently renovated downtown buildings and residents living on the economic margins of Skid Row. In a passionate and remarkably evenhanded entreaty, Delonte Gholston—then the church’s interim youth minister—prayed for God to bring peace to police as well as protestors in Ferguson, to LAPD officers as well as people living on the streets in downtown L.A., to Israelis as well as Palestinians.

“God’s asking, ‘Who will put their bodies in the breach on behalf of the oppressed? Who will take responsibility for what’s been destroyed?’”

“Man, I was just praying,” he later said about what was going through his mind during that benediction.

Pressed for more, Gholston related his perspective on the biblical meaning of covenant—the sacred pact between God and those who believe in Him. For believers, the covenant with God entails showing mercy and compassion toward the stranger as well as those who suffer from poverty and other afflictions. This honoring of neighbor-love, in turn, brings God’s favor and blessings. When human beings breach that covenant by oppressing the stranger or those who are less fortunate, blessings often give way to tumult and discord.

In such times, Gholston said, “God’s asking, ‘Who will put their bodies in the breach on behalf of the oppressed? Who will take responsibility for what’s been destroyed?’”

That skin-in-the-game notion of justice is the heart of Gholston’s identity as a Christian. It also enables him to critique and surmount the barriers of race, creed and privilege in order to serve those who suffer and to address the root causes of their suffering.

“When you say the word ‘justice’ it means 18 different things to every person that you say it to,” Gholston said. “But what I mean when I say justice is the mishpat of God, the shalom of God—that which brings about human flourishing and that which literally repairs and restores things that have been done wrong.”

Gholston, 37, grew up in Washington, D.C. He was raised in a church community that was part of the National Baptist Convention, an African-American denomination that emerged from 19th century Baptist schisms over slavery and race.

He studied political science at Swarthmore College near Philadelphia and felt the call to ministry a few years after he returned to D.C. New City Church appeared on his radar when he moved to Southern California to attend seminary and began to search for a congregation that reflected the sleeves-rolled-up theology that was guiding his call.

Gholston, who as a child listened to recordings of Martin Luther King, Jr’s speeches until he could recite them by heart, was primed at a young age to eschew orthodoxy in favor of activism in his developing faith as a Christian.

“I don’t know that it’s the call of a Christian church to look at a situation like Skid Row and say, yeah, we’re okay that that exists,” he said. “If you want to see human flourishing in Downtown, you can’t look at Skid Row and just say well, we’ll just love them, you know?”

Gholston was looking for a church that engaged those living at the economic and social margins in new ways, and was pleasantly surprised by what he found at New City.

“When I walked into New City, I was just like, what is going on here?” Gholston recalled. “This Asian pastor is ministering to Skid Row folks that are primarily African-American males, and there are whites who are sort of the new loft dwellers,” he said, describing those who have moved into retrofitted buildings in downtown neighborhoods that middle-class and well-off folks used to avoid.

“I’ve seen a lot of different kinds of diversity within white evangelicalism, places that call themselves diverse, and they are ethnically diverse. But I had never encountered that degree of class diversity without it being awkward or asymmetric in some way. And New City just didn’t feel that way at all.”

Yet while New City was creating a new type of community, the world outside its doors seemed stuck in old problems. When Trayvon Martin was killed in Florida in February 2012, Gholston saw it a part of an old and tragic story “of innocent black men being gunned down because people in authority were afraid of them,” he wrote later. As more names became hashtags, Gholston couldn’t help but ponder, “Am I next?” His immediate reaction was to write songs and prayers, but those creative expressions of his pain and frustration were not enough for him.

Instead, he started down a journey to develop the Trust Talks, a series of meetings with facilitated conversation about race and policing in downtown Los Angeles. With a team, he recruited facilitators, community activists, police officers, representatives of the city attorney office, business owners and those who live downtown—whether in lofts high above the bustle of the city or in tents on the sidewalks—to participate.

At the final Trust Talks meeting, Gholston stood on stage in a tunic with a bright orange African print and introduced the theme for the night: Trauma. At tables of 10 or so, participants shared their own stories of trauma for the first half of the evening, then concluded with a discussion about where they find healing.

Gholston sees this work as part of his ministry, though he avoided explicitly Christian language at the Trust Talks event. He opened, for instance, by asking people to say, “We remember,” after he read the names of victims of police violence as well as officers who lost their lives in active duty.

Holding the space between the police and the community is a challenge. He and his Trust Talks co-organizer are at once pastors and activists. Officers, therefore, aren’t always happy with what they say.

“Faith is not just an exercise in thought. If it’s not in my bones, what’s the point?”

“We as clergy are here to be that bridge of healing,” Gholston added. “How can we restore the humanity to the people who have been traumatized over and over again by a system that seems to be fine with the erasure and demonization of black lives?”

Gholston knows as much as anyone that the Trust Talks aren’t going to magically solve Skid Row’s problems overnight. He hopes, though, that it’s the start of an internal transformation for each person in the room. For Gholston, that process is the realization of the shalom of God—an experience of divine grace that’s given freely to everyone in order to nurture individual as well as societal flourishing.

“Faith is not just an exercise in thought,” Gholston said. “If it’s not in my bones, what’s the point? That’s why we say that the internal work is the external work.”

He added, “If God is to come now in a spiritual moment for healing and for wholeness--you know, for personal transformation--then wouldn’t that same God want for that healing and that wholeness to be a social transformation as well?”

That connection between personal and societal healing informs Gholston’s belief that working toward the Kingdom of God means addressing the structural roots of poverty and inequality.

Gholston recently moved back to D.C. to pastor a church of his own. That gig allows him to return to his roots, but also to nurture his growth as an activist in the city where broad structural change in the United States happens—or doesn’t. He continues to look for communities that reflect the kind of social engaged faith that he sees himself continuing to grow into. “I’m always a sojourner, man,” he laughed. “I’m always a pilgrim.”