I posted a question on Facebook at the beginning of 2018: “What ever happened to Black Lives Matter?” The question wasn’t prompted by animosity, despite the disagreements between clergy and BLM. To my surprise, Melina Abdullah, a BLM LA leader, responded.

Many of my fellow Black clergy members have no interest in BLM. Some don’t like the strong LGBTQ focus. Some don’t like their aggressive tactics, which often devolve into confrontation. One event has stuck in the minds of Black clergy: BLM activists disrupted an event in 2015 with Mayor Eric Garcetti at Holman United Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the oldest Black churches in Los Angeles and a touchstone of the civil rights movement. Many of my clergy friends have held this against BLM. I, too, felt some resentment towards BLM for their lack of respect for the traditions of decorum and respect in a House of God.

Yet, I also have admired Blacks Lives Matter from a distance and generally agreed with their proposed goals. We as a Black community must stop the killing of innocent Black lives by biased police officers. Police violence is not a new phenomenon. Jimmie Lee Jackson, a civil rights advocate, was killed by the police in 1965, and Martin Luther King called for pastors to march against this injustice. Today, BLM is answering King’s call. Many of the young people in my church are part of the movement. BLM seems to be the space where the next generation can explore civic engagement on its on terms. In fact, I’ve been told that I was too old to participate in this new movement!

So I was surprised when Melina Abdullah invited me to participate in a BLM demonstration against Los Angeles District Attorney Jackie Lacey for her failure to prosecute police officers accused of bias and undue violence.

I know Jackie Lacey, the first Black female District Attorney, and I felt uncomfortable going to protest against a friend. I prefer to engage with public officials around difficult matters behind closed doors, in contrast to BLM’s method of confrontation in the public square.

Nonetheless, I accepted the invitation. When I got to the site of the protest, Dr. Abdullah immediately embraced me with a hug, though at that point we only knew each other through social media. There were many familiar grassroots civil rights leaders at the event, and people of various ethnic groups, genders and age ranges. I did not see any other church leaders.

Dr. Abdullah asked me to pray to start the program. I had intended to slip into the safe non-confrontational background, but she pulled me to the forefront of the event. I was out of my comfort zone and afraid of being outed by other clergy for supporting Black Lives Matter. I was filled with doubt for even coming! My mind raced for a means of escape, but I am an ordained minister of a social justice denomination. The African Methodist Episcopal Church is known for marching and speaking truth to power. I reluctantly accepted the portable microphone and offered my prayer.

As I started praying for the families of men and women killed by police officers, I was surprised at how comfortable I felt. Following the prayer, I discovered the event was much more than a protest against the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office. It was a method of bringing the community together. And the members of BLM wanted to embrace members of the church.

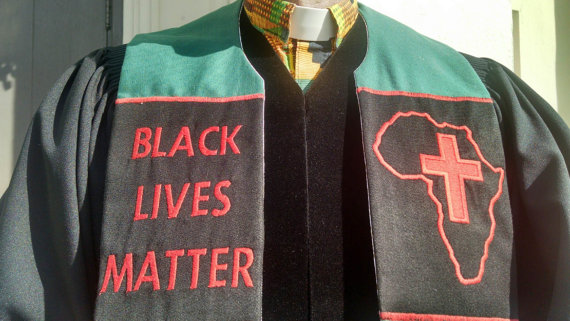

Yet, there was even more significance to my prayer. I was a representative of the AME Church, a mainline denomination, endorsing Black Lives Matter. An old civil rights organization was partnering with a new method of civic engagement. It was a moment of healing for BLM and the Black Church. And it was, for me, confirmation that I need to stay involved with BLM.

I’m sure some members of BLM are still doubtful about Black clergy, and some Black clergy are still reluctant to partner with BLM. As for me and my church, this is the beginning of a new method of community partnerships to end police killings of Black lives.

Video: Watch activist Roslyn Satchel on faith leaders’ role in BLM

Photo Courtesy of wallybryen/Etsy.

Mark Whitlock is a contributing writer for the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.