As the 2022 midterm elections approach, little can be predicted—except, perhaps, that they will further cement the deep divides in our country.

Those divides often extend into religious congregations.

CRCC is a research partner with Exploring the Pandemic Impact on Congregations (EPIC), a research project housed at the Hartford Institute for Religion Research. The project has found that three-quarters of Christian congregations surveyed experienced conflict, mostly mild or moderate, over COVID health measures. In a recent presentation, EPIC’s principal investigator, Scott Thumma, said that surveys found little conflict generally within congregations.

Even in CRCC’s West Coast bubble, our local case studies with the Hartford project have found that many congregations face internal disagreements about issues in the wider culture as well as directions the congregations should go—whether or not these disagreements become conflictual. Moreover, our case studies raise questions about whether this current moment—shaped by the pandemic and the volatile political climate—may be revealing and exacerbating division not only within but also between Christian congregations.

Certainly, political sorting is already in the DNA of many congregations. Some of the churches we have studied as part of EPIC experienced ideological splits long before the pandemic.

In previous work, CRCC identified five “varieties” of American evangelicalism, and to some extent, these varieties map onto congregations in EPIC. For example, “Trump-vangelical” congregations play a central role in promoting nationalist perspectives and furthering right-wing conspiracies, while at the other end of the spectrum, there are groups like “Jesus 4 Revolutionaries,” which centers Gospel narratives of Jesus as an advocate for people on society’s margins.

However, it is important to note that at least within evangelicalism, the political spectrum is not particularly wide. One of the defining characteristics of our largest “variety” of American evangelicals, iVangelicals, is that they tend to focus on individual transformation over large political issues. That orientation is itself politically conservative, though as we note, presented in a “non-offensive” way. Congregations that take this approach, therefore, can be the spiritual home of people with various political perspectives.

When the pandemic arrived, it disrupted many people’s ordinary habits of going to church. For many, that meant checking out from what had been a marginal part of one’s life in the first place. Both national surveys and our local research has found attendance to be down at most churches.

For others, pandemic closures might have presented an opportunity to change churches—perhaps finding a church that more closely aligns with their politics.

Leaders at one of our congregational case studies told us that they lost long-term, committed members who were vocally upset about the church’s decisions to follow their local public health department’s guidance on COVID safety measures.

The initial decision to close their doors had been fairly easy for the church’s leaders. Through a local network of pastors, nearly all the congregations in the area had agreed to go along with the public health guidelines.

But church leaders had to continuously review their decisions and make new ones, such as whether and when the church could meet outside, inside, with masks or without. Each of these decision points presented a new opportunity for conflict—or at least disagreement. At this particular church, these decisions were made through long conversations between lead pastors whose love and appreciation for each other helped them overcome their disagreements about how to proceed. They returned to indoor, unmasked worship more slowly than other churches.

The fact that churches in the area made different decisions gave congregants a choice: They could either continue to worship with their own congregation with safety measures in place, or they could go elsewhere and worship in person or without a mask.

At another church, some members said they visited other churches that had started worshiping in person earlier than their own, even though they ultimately returned to their home church once it re-opened. Today, at both churches, some mask while most do not, with little antagonism shown toward the other.

Of course, these decisions and differences extend beyond COVID policies. Both of these churches pride themselves on their theological and political diversity. One held a program around the 2020 election to work on listening to the other perspective. But then when George Floyd was killed, the congregation attempted to hold difficult conversations about racial injustice over Zoom. One of the pastors told us that it seemed that people forgot all the skills they had worked so hard to cultivate just months earlier. While some left the church over COVID policies, others left out of frustration with its lack of responsiveness to the social issues presented both by the pandemic and a time of racial reckoning.

Through interviews with leaders of different area churches, we are aware that many of those who went to other congregations did so to find a more comfortable political and religious home. These kinds of shifts in membership may ultimately contribute to churches’ moving further to the right or left, with members seeking more like-minded communities in which to worship. Such movement between churches would ultimately serve to reduce conflict internally within individual congregations, while amplifying difference and conflict across Christianity as a whole.

At the same time, many of our congregational case studies continue to have members who hold varying opinions on social and political issues. Indeed, some members found that being separated from the congregation on Sunday morning through the pandemic made them place greater value on being in community with others, regardless of their fellow congregants’ personal opinions.

In CRCC’s 2020 webinar on the impact of politics in congregations, sociologist Russell Jeung suggested that the wider American Christian church could learn from Asian American churches in avoiding hot button topics that are sure to incite conflict. For instance, Jeung said, a Chinese church won’t talk about divisions over Hong Kong or Taiwan. There is no way to talk through or resolve tensions about such issues.

“In the Asian church, we’ve always had pluralism. We’ve always had diversity, but I think we also had a sense of collectivism that comes from our Asian backgrounds that held us together in unity,” Jeung said. He pointed to Christian values of humility, submission and wanting the best for the other as supporting a more collectivist rather than individualistic approach to church disagreements.

We are left with many questions regarding what is really going on within congregations, despite reports from surveys that internal conflict is relatively mild.

How does conflict affect individuals’ decisions about where—or whether—to worship? Why do some seek out congregations that reflect their political persuasion while others seek to maintain diversity within their community of faith? How does the potential for conflict affect one’s decision to go back to church–rather than sitting on your couch or going for a hike, where arguably, one could also encounter God?

What is the impact on society when churches are a place of division—either within or between them? Could congregations be a place to work on the skills needed to live in a diverse society? Could they be a model of how we live together?

Presuming there is some social good in congregations’ bringing people together for a higher purpose, how do you maintain a community of faith in a world of contradictory influences? Is the desire to hold onto community enough to overcome division when a congregation’s leaders have to make a decision (whether on COVID policies or gay marriage)?

At the launch of our cohort for our project on Thriving Congregations, we heard from Fuller Seminary President Mark Labberton, who used the Book of Daniel and the Israelites’ refusal to commit idolatry to reflect on our current moment. “Our world is filled with idols,” Labberton said, adding that idols on both sides drive divisions in congregations. He challenged the faith leaders in the room to examine their own idols, as well as their members’ idols.

“How are we going to sort those and be sure that we only bow down to the living God and not to anyone or anything else?” he said.

Programs that help congregations handle division

Minnesota Churches’ Respectful Conversations

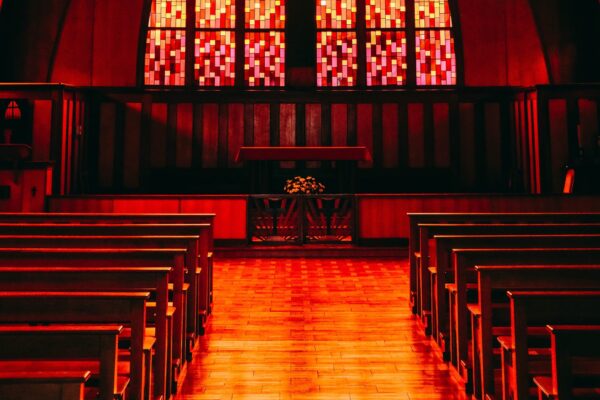

Photo Credit: Adrien Olichon / Pexels

Megan Sweas is the editor and director of communications with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.