This article was originally published by Religion News Service, with the support of CRCC’s global project on engaged spirituality.

YEREVAN, Armenia (RNS) — Home for Lara Aharonian is this capital city whose architecture still bears the heavy stamp of Soviet days. But when her work on behalf of women living on the margins of society becomes too risky, she heads 20 miles west to find solace in Armenia’s spiritual capital, Echmiadzin.

The director of the Women’s Resource Center in Yerevan, Aharonian said she looks to Armenia’s ancient spiritual traditions to stay strong against the rape and death threats she’s received over the years. She also draws strength from women who’ve resisted social and political pressures through nonviolence.

For nearly two decades, Aharonian has made radical love the crucible of her work while empowering women in the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region. She’s helped build peace with women from Azerbaijan and Turkey and created feminist safe spaces in Armenia.

In 2018, following a series of anti-government protests in Armenia, Aharonian came under severe attack from far-right groups after she gave a speech in the National Assembly in support of sex workers, transgender women, Yazidi women and other minorities.

“There was a volley of hate messages against me,” said Aharonian. On her arm is a tattoo reading “Sabr” — “patience” in Arabic, a band of resistance.

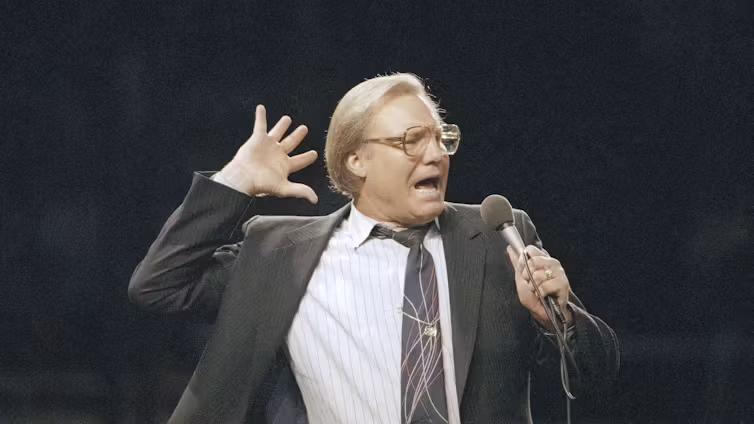

Head bent low in prayer in a pew in Echmiadzin’s 400-year-old Shoghakat Church, Aharonian evokes the nuns who were martyred at the site by the pagan King Trdat before his own conversion to Christianity in the year 301.

Lara Aharonian lights a candle and prays at Shoghakat Church, the site where nuns were martyred during Armenia’s conversion to Christianity in the spiritual capital Echmiadzin.

She lights a candle in their name and circles the church, touching the bases of its walls’ piers to pay her respect to the women who served as paragons of the new faith.

“Shoghakat is a drop of light that appeared during the martyrdom of the nuns,” said Aharonian. “Just as these nuns stood firm in their faith, I want to fight for our identity in this chaotic region.”

Read Priyadarshini Sen’s reflections on visiting an ancient Armenian monastery.

Born in Lebanon to a family that fled the 1915 Armenian genocide, Aharonian spent her early years in hiding and uncertainty as civil war ripped Lebanon apart from 1975 to 1990.

Her family found shelter in the basement of an Armenian Catholic Church when the bombings intensified and militias and army personnel took over Beirut’s streets. As the conflict spiraled out of control, the family fled in boats, rowing to Cyprus to find safety.

After their home in Beirut was bombed in 1989, the family moved to Montreal. Living as a refugees in Canada was an adjustment, but it offered Aharonian stability and education.

While pursuing her master’s degree in comparative literature, she volunteered at community centers to help newly arrived refugees. She cheered women with the mystical practices she learned from her grandmother, reading coffee grounds to start conversations that “put them in touch with their inner strengths,” she said.

Lara Aharonian at the Women’s Resource Center in Yerevan, Armenia.

Lara Aharonian at the Women’s Resource Center in Yerevan, Armenia.

Despite her family’s faith — she grew up listening to stories of Christian saints who changed the world — she became critical of organized religion. She felt the church didn’t follow Jesus’ teachings of tolerance and inclusion, and she began searching for answers in philosophical, religious and anti-establishment literature.

Books such as “The Woman’s Bible,” by the early feminist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, “helped me understand that religious practices were the entry point to understanding people and cultures,” Aharonian said.

Aharonian’s decision to be a human rights defender grew out of her grassroots work over two summers in Nagorno-Karabakh in the late 1990s. A decade before, ethnic Armenians in the region had demanded to be transferred from Soviet Azerbaijan to Soviet Armenia, setting off a war of independence.

“I fell in love with Armenia after volunteering in the conflict area,” she said. “The war had shattered many lives and I felt I could heal the traumas of the afflicted.

“When you grow up amid war and conflict, you become especially sensitive to voices that are stifled, forgotten or excluded from protection,” she said.

“Lara had this incredible ability to draw people in,” said Gayane Hambardzumyan, a fellow activist she met in Karabakh. “We threw ourselves into mobilizing women in Karabakh and tried to break their walls of resistance.”

Lara Aharonian conducts a coffee reading as part of a healing session with feminist activists at her home in Yerevan, Armenia.

Lara Aharonian conducts a coffee reading as part of a healing session with feminist activists at her home in Yerevan, Armenia.

In 2003, Aharonian moved to Armenia and, together with a few other feminists, set up the Women’s Resource Center at Yerevan State University. “My activism started in an informal way,” she said. “We were just gathering women at the university to start conversations about taboo subjects and push against patriarchy.”

In 2008, Aharonian started the country’s first hotline to register sexual violence cases. She campaigned extensively for a new law against sexual violence.

But in 2013, as Armenia prepared to join the Putin-led Eurasian Economic Union, civil society organizations in Armenia were attacked brutally and threats against Aharonian escalated.

“They said they would burn our center and cut our throats,” recalled Aharonian. “Not only did they want me to stop my work, they arrested me at public action campaigns.”

Aharonian saw Russia’s influence as a threat to Armenia’s budding rights-based civic culture.

She began organizing door-to-door campaigns, diversity marches and other events, spoke out for the rights of sexual minorities and revitalized the Coalition to Stop Violence against Women.

But the nonstop death and rape threats from 2013 pushed Aharonian to prioritize self-care.

“Zen mindfulness helped me when my reality started impacting my body and mind,” she said. “It taught me a lot about suffering, hope, love and survival.”

Human rights defender Lara Aharonian prays at Shoghakat Church, the site where a group of unnamed nuns was martyred during Armenia’s conversion to Christianity, in the spiritual capital Echmiadzin.

Aharonian started incorporating some of these meditation techniques at the feminist meetings. Three years ago, these collective care sessions gave rise to a healing retreat held on the outskirts of Yerevan where feminists gather a few times a year to energize one other. They light incense sticks, perform breathing exercises and build solidarity through body painting, dance and music, mask-making and sacred walks.

“Our center is still being developed,” said Aharonian. “I call on the energy of powerful women in our past — saints, writers and change-makers — to help us through difficult times.”

The week before Easter this year, Aharonian visited Echmiadzin again to pay her respect to the women saints. She tied seven knots in their memory, prayed and lit candles. As she passed remote churches and monasteries of the region, she would go inside to reflect on her forebears’ legacy.

The Saghmosavank Monastery in the Aragatsotn province of Armenia.

The Saghmosavank Monastery in the Aragatsotn province of Armenia.

Her favorite is the 13th-century monastic complex at Saghmosavank, atop a precipitous gorge in the Aragatsotn province. In 1991, she helped restore the building after the Soviets withdrew from Armenia. It reminds her of past struggles for preservation of Armenia’s identity and the right to live.

“This place gives me strength and hope,” said Aharonian. “I listen to the silence all around me and think of our rich past to continue the tradition of resistance.”

Priyadarshini Sen is a journalist fellow with the Spiritual Exemplars Project.