This article was originally published by Religion News Service, with the support of CRCC’s global project on engaged spirituality.

(RNS) — New Yorkers of a certain age remember Ruth Messinger as a city councilwoman and later Manhattan borough president whose political achievements were, by dint of the time, feminist, including her 1997 attempt to deprive then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani of a second term and become New York’s first female chief executive — a glass ceiling that has yet to be broken.

At that point, anyone may have reasonably assumed Messinger’s two decades of public service made a complete career.

But Messinger was hardly done.

At 81, she holds the title of Global Ambassador for the American Jewish World Service, after stepping down as president and CEO of the 37-year-old human rights organization in 2016 after 18 years in the job.

As AJWS president, Messinger became for the first time in her life an explicitly Jewish leader, focusing the Jewish community’s attention to oppressed and persecuted communities worldwide, heading campaigns to end the Darfur genocide, against child marriage in India and to oppose violence against women and the LGBT community.

But Messinger’s Judaism has always informed her work. Messinger and her sister were raised on the Upper West Side of Manhattan by working parents who were involved in Jewish social service organizations. She ascribes her own dedication to service, as well as her nose-to-the-grindstone work ethic, to her faith and to her mother’s own estimable example.

“The emphasis was to have structure in your life in order to go out and do the work that is required in the world,” Messinger explained, “particularly the part that came from Judaism was the Jewish obligation to work for justice and equity.”

Her feminism, too, derives from her upbringing, especially from her mother, whom she calls her biggest influence. A graduate of Bryn Mawr College, her mother found herself divided between raising a family and building a career.

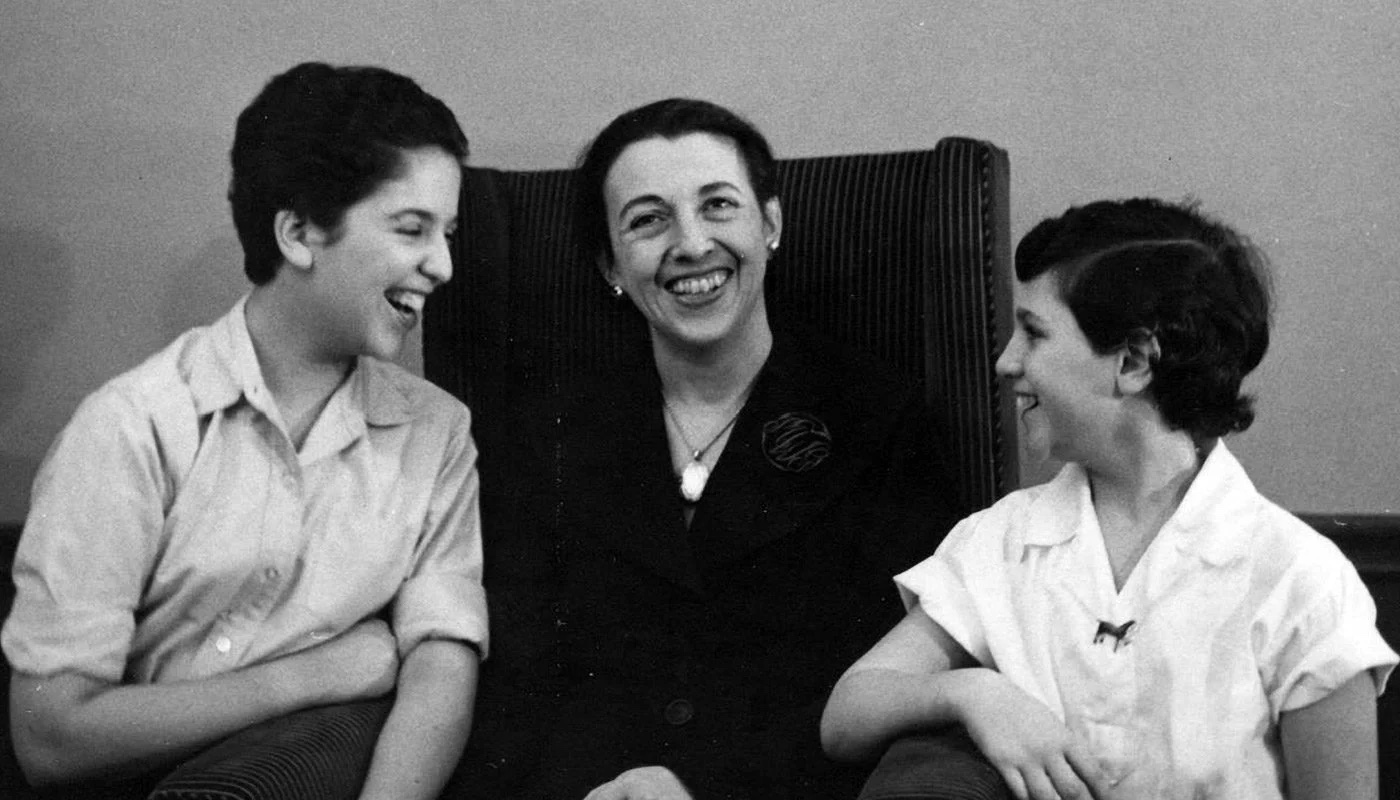

Ruth Messinger, left, with her mother and sister. Photo courtesy of Messinger.

Before Ruth and her sister were born, her mother worked to put Messinger’s father, an accountant, through graduate school in accounting. She got a job at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, a Conservative movement school, and worked there for 55 years.

At the seminary, her mother was immersed in a Judaism that was “concerned with the issues of the day, that promoted the idea that Jews had a role in caring for the other and helping to engage all about what Jews could give to the world,” said Messinger, who identifies as a Reconstructionist Jew today but, when asked her denomination, proudly pronounces that she is a “social justice Jew.”

But Messinger’s mother had complicated feelings about working outside the home. It wasn’t until Messinger was in her 60s that her mother told her how she had gotten an offer early in her career to teach at Queens College, which the school rescinded when they found a man to take the position. “Our mother didn’t want us to think there was prejudice against women,” she said.

On the other hand, Messinger said her mother’s feelings about being a wife, mother and professional at the same time didn’t get fully resolved — though she did it brilliantly — until her mother saw her daughters return to work soon after having children. “My mother admitted that was the first time she felt good about the choice that she had made,” said Messinger.

Indeed, creating a balance between family and work life is still something Messinger, the matriarch of a sprawling family herself, with three children, eight grandchildren and three great-grandchildren, pays great attention to. As she answered questions from a reporter, Messinger cradled a great-grandson in one arm while filling envelopes with her free hand.

After taking a degree in social work (at the University of Oklahoma while her then-husband, Eli Messinger, worked for the U.S. Government Public Health Service), Messinger gravitated toward New York politics in 1975 and was elected to a city council seat in 1977. She worked on many issues during her two decades in elected office, including the betterment of public education and protecting small businesses against gigantic rent hikes. The former concern she ran on when she began her campaign against Giuliani in 1997.

Running as a prosecutor with an oversized focus on policing, Giuliani dismissed her candidacy and her issues. “He called me a liar on the issue of school overcrowding,” she said.

The press largely let Giuliani get away with it. Figuring Giuliani to win and loathe to alienate him — “If they covered me seriously, he would punish them,” she said — her run got “shockingly little coverage.”

When the press did pay attention, she faced questions on gimmicky issues and aspersions cast by the Giuliani camp. “The amount of sexism and misogyny in politics challenged me pretty consistently,” she said, but shrugged it off. “There’s a lot of sexism in society. So of course, there’s a lot of sexism in government.”

After a lopsided vote in Giuliani’s favor, Messinger moved to the international stage. She found at the time that American Jews, while deeply involved in domestic social justice, had little history of working for good abroad with and through a Jewish organization, other than in Israel.

“There were many Jews in the States in organizations showing up for interfaith work — National Conference of Christians and Jews, things like that,” she recalled. “But there were not very many Jews doing that on an international level. AJWS helped fill that gap.” Many Jews worked on international issues with many organizations, explained Messinger, but there were no specifically Jewish organizations working on global human rights issues for people of all backgrounds.

AJWS was working in Africa, Asia and Latin America by the time Messinger joined. She led the effort in the Jewish community and beyond to respond to the Darfur genocide. By doing this, she encouraged the U.S. Jewish community’s increasing interest in the rest of the world. “At AJWS, we pride ourselves particularly on not telling people how they want to be helped,” Messinger said, “and by really paying attention to what kind of help is needed by them — what we can do to support their vision and their work.”

The job, which involved speaking regularly to (and fundraising from) audiences of Jewish people from across the country and around the world, forced her to deepen her understanding of the faith she’d grown up with. “In the last 18 years that I was with AJWS, I was constantly making myself more Jewishly informed using text so that I could talk intelligently and from a Jewish perspective in all the various places that I spoke.”

Ruth Messinger with Robert Bank, who succeeded Messinger as President and CEO of AJWS, during a trip to Cambodia in 2016. Photo by Christine Han, courtesy of AJWS.

Part of her education has been about antisemitism, which has been on the rise for much of her tenure at AJWS. Messinger’s awareness of antisemitism growing up was that it was a serious problem of the past more than the present. While she knew many Jewish families that were survivors of the Holocaust, Messinger’s was not.

Her view of it today respects Jewish people’s deep connection to memory, time and persecution, but her instinct as the leader of a Jewish institution is to be healing-oriented and directed to the many other populations that are victims of hate, intolerance and oppression.

“I think it doesn’t make me popular to say this, but there are people in the Jewish community who are living perfectly comfortable lives and whose life is nevertheless sort of centered around victimhood,” Messinger told me.

“There are different attitudes on the part of survivors as to when and whether to tell their stories,” she added. “Some survivors don’t tell their stories because it’s just too horrible. Some don’t tell their stories because they think, not incorrectly, that they are passing on an unhealthy view of the world to young children.”

Her work today is to recruit rabbis to help communities around the world through the AJWS Global Justice Fellowship. About 15 rabbis a year visit organizations fighting for human rights and also receive training in how to become advocates for human rights.

“We take them to one of the countries where we work for about eight days and get them to really meet the people we are helping on the ground. And then we expect the rabbis to come back and do more public speaking ambassadorial work and activist advocacy work in Washington with us,” she said.

The work with rabbis and with donors is to respond to the Jewish obligation to help the other and the stranger.

Messinger hopes her outward-looking work in the community continues to draw people out and focus on issues outside of their own. “There are people in great need,” said the unstoppable Messinger, “and we have an obligation to respond to those people.”

Click here to read the story on Religion News Service

Soumya Shankar is a journalist fellow with the Spiritual Exemplars Project.