By Caris White

Caris White is a student at Dartmouth College studying religion and art history. The following blog post was an independent project she worked on during a summer internship with the USC Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

The National Museum of American Religion is slated to open in Washington, DC in 2026. It seems strange that in the nation’s capital, where there is a museum for everything, there is not yet an official museum of religion. This new museum will be private, not associated with the Smithsonian — the government-funded national museum entrusted with introducing visitors to many facets of America’s past. While the separation of church and state is a central (if debatably effective) component of American governance, religion’s absence from the Smithsonian network is notable, considering its undeniably long and pervasive history in the United States.

According to Mark O’Neill, an associate professor of arts at the University of Glasgow, “The fact is that in general, for museums, religion scarcely exists as a category. The vast majority of religious objects are either aestheticized as art icons or treated by curators as evidence of the exotic beliefs of peoples remote in time, place and culture, or as local history objects like any others.”

O’Neill’s essay was written in 1996, and much of it still rings true. Debates over what makes religion and religious objects distinct from other artifacts abound in the scholarly community, and many historians are more concerned with telling accurate, comprehensive stories than they are with these abstract definitional debates. Perhaps, the seeming lack of religious recognition in museums stems from curators’ hesitation to set hard parameters on what exactly does and does not constitute “religion,” since a constructive definition of religion is certain to face pushback.

Despite these challenges, scholar Crispin Paine argues that more museums have begun taking religion seriously. “Anthropology and archaeology museums always have done so, but now history and above all art museums are recognizing a duty to explain the meaning that once underlay their ‘historic specimens’ and ‘works of art,’ and once more to allow their visitors to respond to that meaning in their own way.”

There have been a few notable recent developments in the area of museums and religion in Washington, DC over the past decade. In 2016, the Smithsonian Museum of American History hired Dr. Peter Manseau as its first Lilly Endowment Curator of American Religious History. In November 2017, the private, Hobby Lobby-backed Museum of the Bible opened to the public—with great controversy.

With parallel timelines but vastly different curatorial approaches, these two museums provide a window into the burgeoning field of curating religion.

The Museum of the Bible

Museum of the Bible. © Museum of the Bible, 2016.

The Museum of the Bible is a towering 6-floor brick building located near the Washington Mall. Entering this museum is a far cry from the Smithsonian, which is free and open to anyone who happens to stroll through. At the Museum of the Bible, security was at least as tight as a TSA airport screening area—complete with metal detectors and x-ray bag scanners—and entry costs $25 for adults and $20 for students.

Structurally, the museum is beautiful. All six floors are joined by airy staircases, and stained glass windows with descriptive plaques toe the line between church-like adornment and an art exhibit.

Structurally, the museum is beautiful. All six floors are joined by airy staircases, and stained glass windows with descriptive plaques toe the line between church-like adornment and an art exhibit.

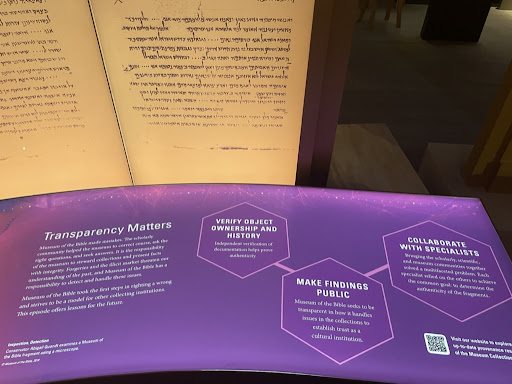

However, the gorgeous (and expensive) Museum of the Bible has come under heavy fire for improperly researching the provenance of its collections, which started as the private collection of the Green family, founders of Hobby Lobby. The Museum’s once headlining collection of Dead Sea Scroll fragments were proved to be fake, which was confirmed in 2020 but suspected by scholars as early as 2014. More recently, it has returned thousands of artifacts proved to be looted from Iraq, and in 2022, it returned an ancient gospel that was looted from a Greek monastery. These recent returns have marked a shift in the Museum of the Bible’s collections policies. Amid increasing criticism from scholars, the museum created an oversight council of scholars to advise the Green family and ensure that the museum’s new acquisitions had more reputable provenance.

If you visit the museum’s Dead Sea Scrolls exhibit today, you’ll see an entire wall of documentary-style footage about the museum’s “learning experience.” The descriptive plaques would lead you to believe that the museum was a trailblazer of provenance research and cooperation with scholars. Yet, even though scholars first voiced concerns about the fragments’ authenticity in 2014, the issue was not mentioned in the museum’s lengthy 2016 book about the artifacts. Steven Bickley, the museum’s vice president of marketing, told The Atlantic, “We don’t have any concerns about our collection,” just before the museum opened in 2017.

If you visit the museum’s Dead Sea Scrolls exhibit today, you’ll see an entire wall of documentary-style footage about the museum’s “learning experience.” The descriptive plaques would lead you to believe that the museum was a trailblazer of provenance research and cooperation with scholars. Yet, even though scholars first voiced concerns about the fragments’ authenticity in 2014, the issue was not mentioned in the museum’s lengthy 2016 book about the artifacts. Steven Bickley, the museum’s vice president of marketing, told The Atlantic, “We don’t have any concerns about our collection,” just before the museum opened in 2017.

The evangelical nature of the Green’s original museum plan shines through in its curatorial practices. It’s hard to view the Museum of the Bible as a neutral scholarly authority, when in its 2011 tax filings, the organization “stated its purpose was ‘to bring to life the living Word of God, to tell its compelling story of preservation, and to inspire confidence in the absolute authority and reliability of the Bible.’”

Today, the Museum’s stated purpose is more neutral—“inviting all people to engage with the transformative power of the Bible.” Yet, Steve Green still chairs the Museum’s board. Green argues that the Bible has been a central guiding force for our nation’s destiny and identity in The Bible in America. Considering the Museum’s heavy focus on American Protestantism, it seems that Green’s personal beliefs percolated into the Museum collections—which originated from his personal collection in the first place.

Although the Museum of the Bible is currently on a mission to clean up its act, questions remain about whether new provenance policies and a fresh team of recruited scholars is enough. Even if all of its collections had squeaky-clean documentation, the fact remains that it approaches the Bible with a relatively un-inclusive lens, according to The Atlantic. While the Museum’s walls are covered in Hebrew script, Arabic is almost nowhere to be found—an interesting juxtaposition, considering both are Semetic languages, and the Bible shares a close relationship with Islam and the Qur’an. The Bible’s influence on American Protestantism is declared loudly, but its importance to Eastern Christian traditions and Islam receives very little discussion.

The Smithsonian Museum of American History

At the Smithsonian Museum of American History—home to the recently established Center for the Understanding of Religion in American History (CURAH)—the curatorial lens is much wider but also decidedly less focused. In some ways, this lack of focus is overwhelming. Whereas the Museum of the Bible presents an artfully curated and streamlined narrative of the Bible’s history, content, and significance, the Museum of American History offers no such clarity. Instead, it presents visitors with a messy, figure-it-out story, where narratives of meaning and belonging are still being written.

This summer, the Museum of American History presented the “Discovery and Revelation” exhibit, curated by Manseau, which traces some of the myriad ways religion and science have mingled throughout American history. The exhibit included a range of artifacts, from footage of astronauts reading Genesis while in space, to Thomas Jefferson’s personal Bible with all of the passages he didn’t believe carefully cut out. Unlike the Museum of the Bible, there was no walkable timeline of this history — no distilled, easy to understand summary of the long and sometimes contentious relationship between science and religion.

According to Lauren Safranek, Director of CURAH, the museum isn’t aiming to provide a comprehensive explanation of religion in America, nor could it.

“We can’t tell a complete story about anything,” she says. “Everything on the walls is not everything, and you’d be so sorely mistaken if you thought it was.”

As America’s national museum, the Smithsonian also occupies a place of special influence, and a razor thin line between representation and interpretation, on the one hand, and advocacy for a particular narrative or historical through line, on the other. It’s impossible to be comprehensive, evenhanded, completely accurate, uncritical and discerning all at once. Museum curators and directors, after all, are human.

“We have to be really careful not to say something wrong, or too lightly, or rush over something that needs more time, maybe more than other topics,” Safranek says. “We’re not teaching religion; we’re not promoting religion; we’re not critiquing; we’re not doing anything with that. We are telling the history of religion: good and bad, positive and negative, diverse and not.”

Safranek also speculated that the Smithsonian’s unique role as a government-funded institution is one of the reasons the American History Museum’s religion initiative was only undertaken recently.

Now that the Smithsonian has steered toward curating religion, the path forward is largely untrodden, and Safranek said that she and Manseau are creating the new rubric as they go.

“There’s no formalized, ‘right’ method. It’s up to us to figure out the best thing to do in each individualized case,” Safranek said. “Things cannot be perfect, but you can strive. You can strive for better, and there’s got to be some sort of middle ground between acknowledging we can’t do everything, and also trying to be as thorough and inclusive as possible. I’m still building it in my mind, trying to figure out what that is.”

Where Do We Go From Here?

With construction underway at the upcoming National Museum of American Religion, it’s clear that questions about religion, curatorialship and American identity still demand our attention. Religion as an academic field offers remarkably few right answers in its engagement with its subject. Each definition it provides, it also undermines–a process of continuous argumentation that feels frustratingly convoluted at times. This is an incredibly challenging trajectory to map onto museum exhibits, but centering pluralism, for example, doesn’t have to be a futile effort. Religion Curator Teddy Reeves’s recent video project for the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture received over 24 Telly Awards — proof that weaving together multiple stories does not have to be a recipe for confusion. Embracing religious pluralism saddles museum-goers with the difficult task of evaluating multiple—sometimes competing—storylines, but it also liberates them from consuming an oversimplified version of “American religion.”

Curators have a responsibility—and the years of education—to choose meaningful artifacts and explain their context and relevance to visitors lacking in particular expertise. They do not, however, have the final say on what exactly constitutes American religion. What if—instead of giving answers—the National Museum of American Religion started a conversation with its visitors? American religion isn’t just contained within the pages of a history textbook or the clippings of Thomas Jefferson’s Bible. American Religion is happening right now, and as long as people are still believing, debating and changing, its story will never be fully written.